Policy against sexual harassment necessary

Yangchen C Rinzin

Long ago, even today in some rural villages, men and women share crude jokes and even touch each other inappropriately while working in groups in the fields.

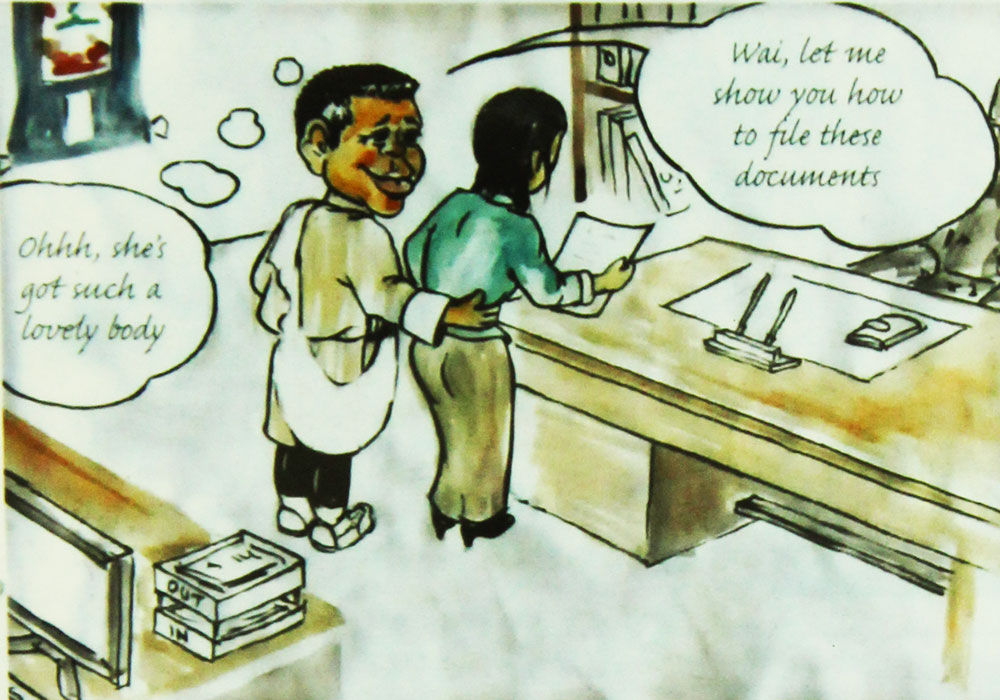

This playful age-old culture, many say, is being used to normalise sexual harassment today. The work place has changed from fields to offices and many now question if Bhutanese society is normalising sexual harassment in the name of culture.

Those following the issue closely say times have changed and with increasing sexual harassment cases, there has to be a holistic policy in every organisation to deal with workplace sexual harassment.

A few years ago, the Royal Civil Service Commission has instituted the “Go to Person” to encourage women to come forward to report sexual harassment cases and labour ministry mandates all corporations and organisations to have service rules and regulations to address such cases.

But the rules and regulations, going by records, remained only on paper and many women, who faced sexual harassment at workplaces, are not comfortable reporting it. Even if they do, they are not taken seriously.

Sexual harassment, according to Penal Code of Bhutan includes staring or leering, unwelcome touching, suggestive comments, taunts, insults or jokes, displaying pornographic images, sending sexually explicit emails or text messages, and repeated sexual or romantic requests. It also includes behaviours such as sexual assault, stalking or indecent exposure.

Many said it was time to change the perception that sexual comments are harmless flirtation or are trivial and that if not done intentionally, cannot be considered harassment.

Sexual harassment at workplace is referred to as “unwelcome verbal, visual, or physical conduct of a sexual nature that is severe or pervasive and affects working conditions or creates a hostile work environment.”

In most cases, victims are female and it is, often, between a superior male officer and female subordinate.

An independent researcher based in Thimphu said that from an academic view, such a concept is known as power relations or power relationships or accommodation of power.

“When a superior makes any kind of nasty remarks or sexual jokes, the subordinate would be forced to accept the joke even if it was in terms of sexual harassment,” he said. “This happens because they believe they should not respond while on the other hand the superior feels it’s fine to joke.”

The academician also said with changing times, the acceptance is changing. “These are emerging problems and we must fix them.”

A programme officer with the RENEW, Yangchi Pema, said the society is normalising sexual harassment because it is difficult to prove especially when it requires evidence and witnesses.

“Most victims today face pressure from all sides to mediate and withdraw the case,” she said. “Such practice over the years has made women lose trust in the system and do not come forward especially when she is asked to prove the harassment.”

Experts say there is a need for awareness on sexual harassment at a regular interval in different places if we want to safeguard girls and women. Many say people still do not even know the definition of sexual harassment.

“In our country, sexual harassment is still unclear because of cultural baggage and it’s difficult to tackle,” Yangchi Pema said.

A researcher said that even if few people speak up, it will deter people from indulging in such behaviour. “Victims need support from the system to fight, including support from female superiors. Our women must gain confidence in the system.”

An independent journalist, Namgay Zam, said that in many cases, women are not able to report because the society, in the name of culture, concludes the victim as hysterical or overreacting.

“There are cases where women have been told they are overreacting and they should let it go because they’re not raped,” she said. “Another is the backlash of discrimination where they are being judged by people.”

Namgay Zam said that these are the reasons why women do not come forward. “Only now we begin to understand that women should not accept it if we feel uncomfortable.”

Sexual harassment policy

Many experts feel that it was time for organisations to have an internal sexual harassment policy that would clearly spell out their stand on sexual harassment. It must spell out where the women can report, internal or external mechanisms to resolve, and who is the focal person the victim can reach first.

They say a policy could be a first step towards dealing with sexual harassment.

Experts shared that such a policy should be in detail instead of one or two pages of sexual harassment clauses mentioned in the internal service rules and regulations.

Yangchi Pema said to have such a policy, the company must take this as a personal agenda and leadership is vital to make it successful.

She added the policy must also include preventive measures and awareness programmes.

According to her, many policy on sexual harassment with organisations are a copied from the labour ministry’s Act.

Despite having service rules, many say it was only on paper and lacked implementation.

A civil servant said some agencies have created awareness on the ‘Go to Person’ initiative. “The finance secretary visited all employees of Department of National Property and created awareness on sexual harassment when she was heading it.”

He said it depends on the head of organisations and we could address sexual harassment if leaders prioritise it.

Although many said women misuse sexual harassment for personal gains, officials said a strong policy would ensure no one could take advantage of each other.

A police official said they take time to investigate sexual harassment cases to ensure there is strong evidence. “We take it seriously but we also have to establish the case.”