Nima Wangdi

Bhutan aims at eliminating malaria by 2022 after it failed twice, once in 2018 and the other in 2020.

Officials said that they could not eliminate it in 2020 due to the disruption that the Covid-19 pandemic caused.

A Program Analyst of the Vector-borne Disease Control Programme in Gelephu, Tobgyal said, since the detection of Covid-19, people’s movement was restricted, hampering the usual malaria prevention programs. “With the Covid-19 pandemic, malaria was almost forgotten, even among the people living in the high-risk areas.”

He said it hampered ex-country capacity building programmes like training. “Prioritised in-country training was conducted,” he said, adding that everything is being revitalised today, including the Community Action Group.

Tobgyal said that in July and August there were 31 malaria cases, which was more than 50 percent of the total number of cases. The first nationwide lockdown was also declared during this time.

Records with the programme showed that there were 54 malaria cases in 2018, 42 in 2019 and 54 in 2020. “There were no deaths from 2019 onward to date. There was one death each in 2017 and 2018,” he said.

Officials were of the view that they could eliminate malaria by 2022 if everything went well.

Tobgyal said there are 23 cases this year so far, out of which eight are considered to be indigenous.

He said that all the places in seven dzongkhags that border India are vulnerable to malaria. They are Nganglam in Pemagatshel, Lhamoidzingkha in Dagana, Phuentsholing in Chukha, Panbang in Zhemgang, Gelephu in Sarpang, Samtse, and Samdrupjongkhar.

“However, Samtse was certified malaria-free in 2015, Lhamoidzingkha and Panbang in 2018 and Nganglam in 2017. There were no cases seen in Phuentsholing and Samdrupjongkhar for the last two years and they too will be certified malaria-free if they did not record cases this year,” Tobgyal said.

Any dzongkhag that sees no malaria cases for three consecutive years gets the malaria-free certification, he said.

He said people are incorrect in believing that malaria doesn’t occur in the winter months.

“Although the number of mosquitos decreases in winter, there is still a risk of spreading malaria,” he said. “That is why more deaths were observed in winters, as people don’t come to the hospital when they have symptoms.”

Public Health Director Tandin Dorji said malaria activities could be disrupted if there are lockdowns and outbreaks of Covid-19. “The same activities on both sides of the border must be carried out if we are to eliminate the disease. We have already held meetings with our counterparts at the local level,” he said.

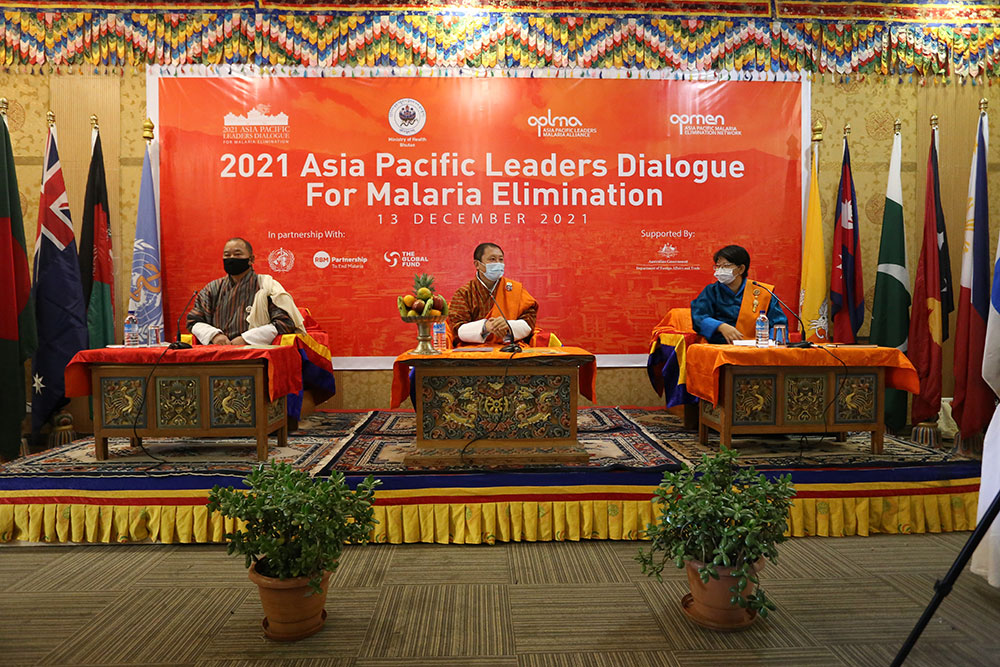

During the 2021 Asia Pacific Leaders’ Dialogue for Malaria Elimination held virtually yesterday, Health Minister Dechen Wangmo said, the ministry instituted a committee for disease elimination in 2019 and malaria was included as an important agenda. “We also have a malaria programme.”

She also presented that the Ministry of Health is also taking the cross-sectorial approach in fighting malaria.

Foreign Minister Tandin Dorji, who attended the inaugural ceremony of the dialogue, said South-East Asia countries should step up the fight against malaria through political leadership and regional collaboration to realise the target of eliminating malaria by 2030.

Regional Director of WHO, South-East Asia region, Dr Poonam Khetrapal Singh said, in 2020, Bhutan, Timor Leste, DPR Kora, and Nepal reported zero malaria indigenous deaths.

“The Maldives and Sri Lanka maintained a malaria-free state. Despite minor setbacks, five countries of the region, including Thailand, are actively pursuing the elimination,” she said.

“Out of these, Bhutan, Nepal and Timor Leste are close. In 2019, there were only two indigenous cases in Bhutan. But in 2020, it reported 23 due to an outbreak at the international border,” she said.

“Cross border issues must be addressed early and revisited often,” she said.