Trongsa Penlop’s Gift to the 13th Dalai Lama

In 1901, the Trongsa Penlop deputed his representative, to deliver gifts to His Holiness the 13th Dalai Lama. In August 1901, the Kutshab delivered two elephants and some leopards. In addition, he successfully transported His Holiness’s newly purchased Bengal tigers and the English ponies from India for his menagerie in Lhasa. From historical records, we learn that the Chogyal of Sikkim had previously presented some elephants but none had survived.

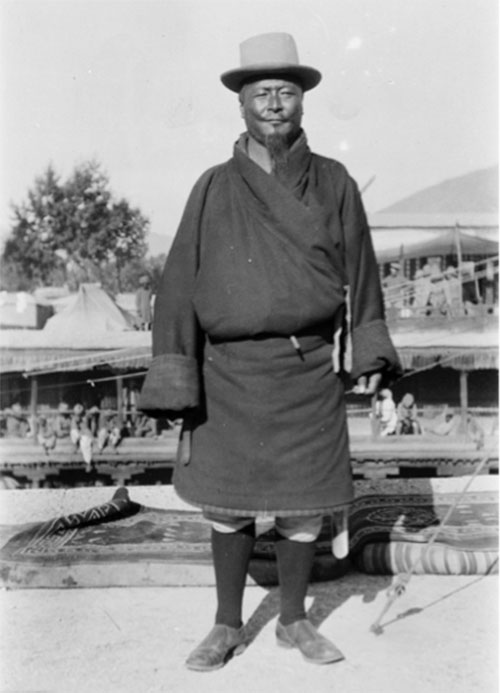

At the time, the Trongsa Penlop was Gongsar Ugyen Wangchuck (1862-1926). By that time, he had emerged as the strongest ruler. Six years later, he was to be elected as the first hereditary monarch of Bhutan. Based in the Indian hill station of Kalimpong, the Penlop’s Kutshab was Ugyen Dorji (1855-1916). Popularly known as Kazi Ugyen, he had been appointed as Bhutan’s representative of South Bhutan just the previous year. His Holiness the 13th Dalai Lama Thubten Gyatso, (1876-1933) was the God King and considered the absolute spiritual and political ruler of Tibet. For his socio-economic reforms, His Holiness is respectfully referred to as the “The Great Thirteenth.”

When Lord Curzon, Viceroy of India (1898-1905) learnt about this mission, he took advantage and sent a secret letter to, “The Great Thirteenth.”

Sightings

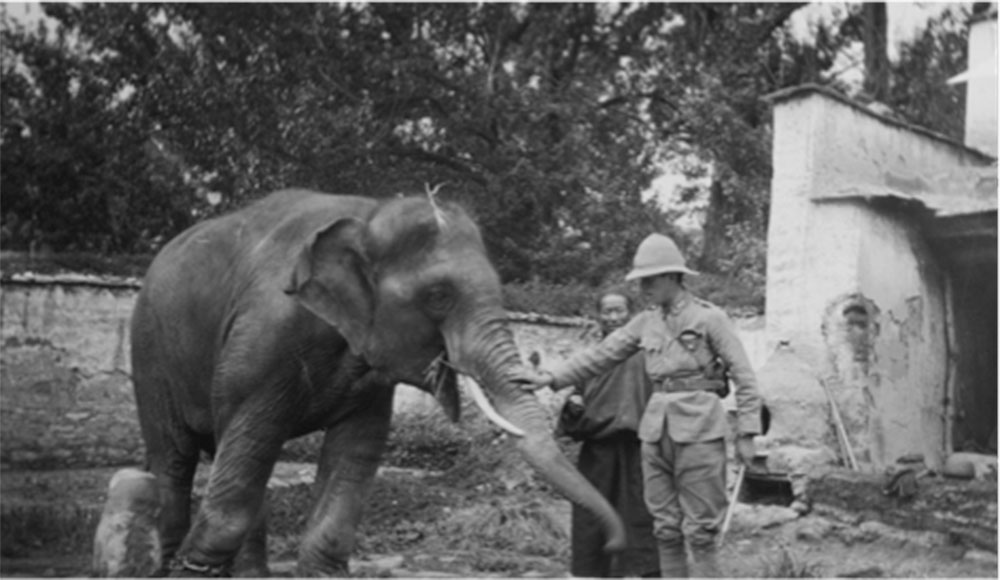

Records of the sighting of the mammals are mentioned by at least five British Officers. The first two, were Lt. Col. Frederick Marshman Bailey (1882-1967) and Lt. Col. Dr Laurence Austine Waddell (1854-1938). Both were members of the 1903-4 Younghusband Expedition to Tibet. However, the two officers mention only the elephant and leopard but not the other animals. At the time, Bailey was a young Captain and serving as the British trade agent in Yatung. The photos he took are held in the British Library and captioned as “The Dalai Lama’s Elephants [Lhasa].”

Bailey later became the British Trade Agent at Gyantse and Chumbi before being appointed as the Political Officer of Sikkim and Bhutan. Based in Gangtok, as a naturalist, keen on trophy hunting and on collecting zoological specimens he was easily able to pursue his passion. An enthusiastic photographer, he was also a linguist. Driven by his interests, he managed to sniff out the elephant kept in the Norbulinka Palace and capture six photos of the animal.

The second British officer who was interested in the elephant was Waddell. He was the expedition’s surgeon and like Bailey had multiple interests. Waddell was an explorer and, as a scholar, deeply interested in Tibet. As an amateur archaeologist, the Scot was comfortable in the mountains. Details about the elephant appear in his book “Lhasa and its Mysteries” published in 1905.

When the two British officers arrived in Lhasa in 1903, they found only one of the elephants had survived. The surviving elephant was described as the second elephant that was a “young single tusker, about 8 ft.”

The third officer who made record of the gifts from Bhutan was S.W Laden La (1876-1936). As the officer of the Imperial Police, and confidant of the British, he visited Lhasa many times. He saw not only the elephants and the leopards but also the tigers and English ponies.

Laden La’s information is based on his meeting with Ovisha Norzunoff who was the secretary and interpreter of Agvan Dorjiev (1854-1938). Born in Russia, Dorjiev was a monk of Gelug school of Buddhism and suspected of influencing the Tibetans. Between 1898 and 1901, His Holiness sent the Gelug monk to Russia three times to get political and military support for Tibet.

Laden La journal entry for 10 September 1901 reproduced in the book, “A Man of the Frontier: S. W. Laden La (1876-1936)” by Nicholas and Deki Rhodes (2006), reads: “Arrived at Jorebungalow: met Geshela Lama who is a well-known Lama…resident of Jorebungalow & went to Lhasa on pilgrimage with Kunzang Gurmed of Jorebungalow & Kazi Ugyen, Govt. Agent of Kalimpong – though great efforts have been to record many important matters, but he seems to be quite innocent. From our conversation I ascertained that Kazi Ugyen, Govt. Agent of Bhutan safely reached Lhasa with his servants and representation. Kazi Ugyen had with him 2 elephants, some English ponies, tigers & leopards with him, but one of the elephants died near Tashilhumpo,” in Shigatse.

The Jewel Park

The Great Thirteenth’s fondness for animals is legendary. In his 89-acre garden of the Norbulinka Palace, he kept a mini zoo with various exotic wild animals.

Dubbed as the largest garden in Tibet, the, Jewel Park was the traditional summer palace of the Dalai Lamas. Built in 1755, it is a short distance south-west of the Potala Palace.

The Route

While the details of the daunting task of how Kutshab Ugyen Dorji transported the elephants and other animals to Lhasa are yet to surface, it is most likely the route was the same one used later by the Younghusband mission. One of the outcomes of this infamous mission was the transformation of the Kalimpong to Lhasa mule track to a cart road. The Imperial force used this route to move 3,000 soldiers and 7,000 support staff.

It is most likely that Kazi Ugyen used the same old trade route. The route involves crossing at least two passes: Jelapla (4,270m) that is the border between Sikkim and Tibet and Nathula (4,310m), before descending into Chumbi valley and then crossing the settlements of Phari, Guru, Gyantse, Karos, Chusil and finally crossing the Tsangpo River before entering Lhasa.

As Laden La mentions the death of one of the elephants at Tashilhunpo which is in Shigatse, it seems there was a deviation from the old route. One logical explanation for the deviation could be because of the ease for the elephant to cross the Tsangpo River.

Interestingly, almost ten years later, The Great Thirteenth had to use part of this track to flee for his life. On 12 February 1910, the Grand Lama fled his homeland to India. Historical records state that He and his party covered about 500 kms in nine days to reach Sikkim.

It is most likely that the Trongsa Penlop’s elephants were already domesticated. Given the distance and terrain, it is highly possible that their mahouts rode them up to Lhasa. The warm, wet and thickly vegetated South Bhutan is the natural habitat of elephants. While there is no evidence, given the proximity to Kalimpong, it is likely that these two elephants were from Sarpang dzongkhag.

The cold dry Lhasa climate is not suitable for elephants. So, Laden La records of one perishing in Tashilhumpo and the Sikkim Chogyal’s elephants not surviving in Lhasa does not come as a surprise.

In Buddhism, elephants are associated with Buddha’s birth story. The mammal symbolizes strength, wisdom, peace and represents Buddha’s teachings and made a perfect gift to the God King.

In 1901, Kazi Ugyen Dorji successfully delivered his master, Trongsa Penlop’s gift of two elephants and a leopard including The Great Thirteenth’s purchase of tigers and English ponies to Lhasa but the same cannot be said for the Viceroy’s letter.

The Viceroy’s Letter

Part II

While Kazi Ugyen Dorji succeeded in delivering the Trongsa Penlop’s gifts of elephant and the leopard to His Holiness the 13th Dalai Lama, the same cannot be said for Lord Curzon’s letter.

At the time, The Great Game was in full play and at its height. The rivalry between the British Empire and the Tsarist Russia ran from 1830 to 1907. Tibet was at the heart of the Game and control of the forbidden country was of utmost importance for strategic and commercial reasons.

Termed as the most contentious event in the Anglo-Tibetan relationship, the Great Thirteenth’s refusal to accept the letter and returning it with its seal still intact further made the British nervous about the relationship between Tibet and Russia. This eventually led to the military invasion of Tibet by a British force under Younghusband in 1903-4. The Tibetan resisted fiercely but were outnumbered by the British storming onto the Roof of the World.

The Trongsa Penlop used his personal influence with both Younghusband and The Great Thirteenth to bring out an agreement. It was the turning point of relationship between Bhutan and the British.

In 1899 Lord Curzon was appointed Viceroy of India. He finished his term of office in 1905. Based on unfounded information, he feared Russian influence on Tibet. Paranoid about Russia’s stance in Tibet, the Viceroy was determined to open communication channels but his efforts were futile. At the time, Tibet preserved an isolationist policy and the 13 Dalia Lama refused to accept any communications.

Waddell provides an account of the attempt in his book. “The first of these letters was dispatched in August 1900 from Ladakh by our political officer there, who travelled as far as Gartok, several week’s journey within Tibet, to deliver the letter to the Tibetan governor or Garpon of that district for transmission to Lhasa. This official, however, returned it a few weeks later with the message that he dared not forward it as promised.”

Kazi Ugyen Dorji was already familiar with Tibet. Two years earlier in 1898, he had trekked up to Lhasa and had successfully delivered Trongsa Penlop’s gift to the, “The Great Thirteenth.” While details are yet to emerge, the Bengal Government used the occasion to send horses for the Tibetan ruler.

The Rhodes in their book mention that “from 1899, Kazi Uygen Dorji, the Bhutanese Agent in Kalimpong, had been to Lhasa and delivered the letters from the Indian Government to the Dalai Lama, but no replies had been received.”

So, when the British government learnt about Kazi Ugyen Dorji’s 1901 mission to Lhasa, they ceased the opportunity and sent a letter with him for the God King. Waddell writes that in June 1901, the second letter was sent from Darjeeling along with the previously undelivered one through Ugyen Kazi.

Nepal Elephants

Following Sikkim and Bhutan, Nepal too presented His Holiness with elephants. In 1920, when Sir Charles Bell (1870-1945) visited Tibet, he found a pair of elephants gifted by Nepal. As part of a diplomatic mission, he took photos which are in the custody of the British Library but are yet to be digitized. The caption of the photo reads “Gift from Nepal.”

Oral stories are told how local people were engaged to build mud houses at all the pit stops for the Nepalese elephants after the Sikkimese’s and one of the Bhutanese elephants did not make it to Lhasa.

It seems that Bell was the only one to enjoy the high honour of visiting the forbidden park and seeing the animals. He was the fourth British officer to attest the existence of the wild animals in Lhasa.

In his book, “Portrait of a Dalai Lama: The Life and Times of the Great Thirteenth” (1946) he attests the existence of the Bengal tiger which was kept in a large but flimsy cage. He also saw the leopard amongst many other animals, He remarked on the Dalai Lama’s love for beautiful surroundings, his passion for flowers, fondness for animals and his love for privacy.

The book provides more information on the Jewel Park. It states that the garden occupied half a square mile, with each side being about half a mile in length. Inside the enclosure was a second enclosure, fortified by 12 feet high walls which were some 200 yards long on each side. Designated as the forbidden ground, except for two close attendants, nobody was allowed inside this conservatory.

Nepean photo of the elephant

Bell writes about his visit of the enclosure on the 30 November with His Holiness as his guide. He said he could recognize most of the flowers but was not impressed with the gardening skills. He noticed the wild animals and wrote about them.

Bell said, “I noticed two barking deer and a musk deer; also, a male burrhel, one of the smaller varieties of wild sheep with spreading horns. One cage holds a leopard, another a Bengali tiger with a magnificent coat, due to the cold of the Tibetan winter. In the corner of garden are half dozen big brown monkeys from the province of Kongo. In one cage there were three porcupines, in another the large Tibetan snowcock with some Chinese pheasants. All the animals and birds, whether in cages or not, are well cared for.”

In 1936, Evan Yorke Nepean (1909-2002), who was the fifth British officer to see, The Great Thirteenth’s elephant in Lhasa, photographed it. Part of Sir Basil Gould’s Mission to Lhasa, he was from the Royal Corps of Signals and as the signals officer of the Mission spent three months in Lhasa, during which time he may have taken his photo.

Nepean’s photo is with the Pitt Rivers Museum. The caption of the photo reads, “13th Dalai Lama’s elephant outside Potala Palace. The elephant is being ridden along the path in front of the south face of the Potala.

Hannibal

Sikkimese, Bhutanese and Nepalese elephants are not the first in history to cross high mountain passes. In 218 BCE the Carthaginian General Hannibal crossed the Swiss Alps with 37 or 38 North African forest elephants and successfully ambushed the invincible Roman Empire. Only one elephant survived but Hannibal’s strategy is unprecedented in the history of warfare.

His Holiness love for animals is legendary. From personal correspondences between the 13th Dalai Lama and Kazi Ugyen Dorji, we find that over the years, the duo developed a personal relationship. The latter helped transport many more animals and birds for His Holiness’s mini zoo in Lhasa.

While there are no records of the Trongsa Penlop ever seeing elephants, his son the Second King saw them for the first time in India in 1923. According to a White Paper, when His Majesty Jigme Wangchuck (1905-1952) visited Dewangiri with his two younger brothers in February that year, the Political Officer in Sikkim arranged a one-night trip to Guwahati where he saw his first elephant.

Contributed by

Tshering Tashi