Changla or paddy cultivation has begun in Paro. Terraces everywhere are filled with young shoots.

But in Doteng, it is just beginning. Here the terraces had lain empty because damkar – a traditional practice where a lead farmer starts paddy transplantation based on astrological predictions – could not be started sooner.

The rice growers of Doteng gewog have been following this tradition since time immemorial.

The night before the damkar, Desam, 68, collected three bundles of rice seedlings and kept them at her altar room overnight.

After the instructions from the astrologer, she calls her neighbours. A 30-year-old woman, born in the monkey year, must start transplantation.

“Yangchen will plant the saplings tomorrow,” says Desam.

Farmers consider the importance of astrology in all aspects of their lives, even to begin an agriculture work.

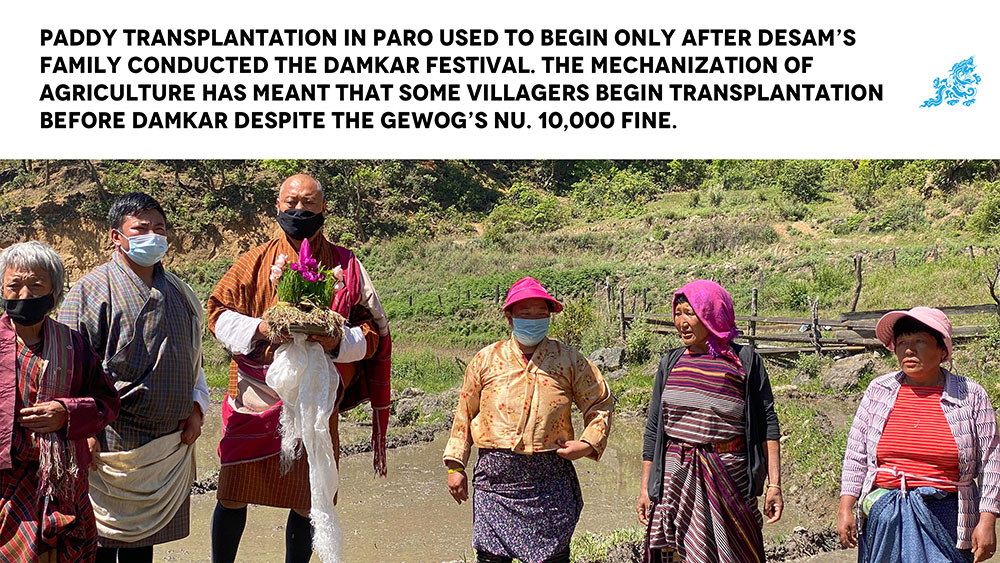

Early morning on Sunday, the astrologer begins Lhabsang Thruesel and Soelkha to appease local deities. The gewog officials, led by gup, mangmi and tshogpas join the celebration with the zhudrel ceremony.

After quick breakfast, the gup collects the bunch of rice saplings from the Chesham, praying for a bountiful harvest and takes it to the paddy field. Gup and mangmi, along with Yangchen, Desam and three other women, face Chumigang—the hill opposite Desam’s house and pray for a bountiful year.

According to sources, Desam’s family has to lead the plantation as her main door faces Chumigang (rice hill).

Doteng mangmi, Chimi Dorji, said that every agricultural event in the gewog must face Chumigang as the hill is believed to bless the gewog with good agriculture yield.

Yangchen begins the plantation. Soon, women jump into fields with songs.

Gup Letho announces: “Paddy transplantation officially begins!”

According to Letho, damkar is essential as it starts on a good day as per astrology to prevent pests and crop diseases. “It is hard work. Farmers have to work round the clock for around six months until they harvest the rice.”

In Paro, no village would begin rice transplantation without damkar but mechanised farming has changed this. Except for Doteng and some communities in Paro, damkar tradition has been on decline.

Realising the importance of this tradition, Letho said that the gewog conducted meetings with locals to restrict paddy transplantation before the damkar ceremony in Dasam’s house. That’s why the gewog officials are here today to help preserve this unique tradition.

“We have notified all the farmers about the damkar,” he said.

As per the gewog’s resolution, no one is allowed to begin rice transplantation before damkar. Those failing to abide by the rule must pay a fine of Nu 10,000.

Desam remembers her childhood days with her grandmother celebrating damkar like losar. “Technology has made work much easier, but it breaks my heart to see our traditions disappear.”

When Desam was in her early twenties, people lost rice to a ragged stunt which reduces yield due to unfilled grains and loss of plant density. That year, a household from another village had led the damkar.

Desam said that she did not lead the damkar that year, as another family already had. “It was a disastrous year.”

Letho said, after that, the gewog in consultation with farmers decided to restrict other households from leading the damkar.

Desam has been leading the plantation since then.

Every year, Desam looks forward to damkar. She said that it was the best time to gather and celebrate before the long, arduous work.

Letho said that the gewog had to support the family considering the risk of losing the tradition. “We are planning to allot a minimal budget for the damkar.”

However, according to Pem, a farmer, mechanised paddy transplantation had to start earlier as the saplings took longer to bear the grains. “If we wait until the damkar, our rice won’t grow properly.”

Local leaders agreed that it would be difficult for farmers to follow damkar timing with mechanised rice plantation.

Some households near the gewog office are planning to use machines to plant rice due to labour shortage.

Letho said that the gewog would consult with the locals and decide a similar practice for those using machines to preserve the tradition. “We can’t let this practice disappear. We also want to encourage farmers to use technology.”

By Phub Dem | Paro

Edited by Jigme Wangchuk