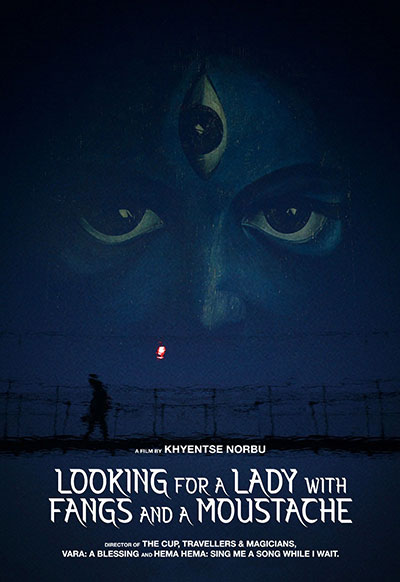

In the new film from Dzongsar Jamyang Khyentse Norbu, a doomed man is thrust on a spiritual quest to find a lady with fangs and a moustache who could very well save him

In his fifth feature, ‘Looking For A Lady With Fangs And A Moustache’ which premiered on virtual cinema recently, the Bhutan-born lama and write-director Dzongsar Jamyang Khyentse Norbu weaves a quiet, deliberately paced and deceptively simple story of a man who on discovering he has just seven days to live is propelled on a nerve-racking spiritual journey.

Tenzin (Tsering Tashi Gyalthang), a strapping human specie and a capitalist to boot, is a man committed to the supremacy of reason and skeptical of everything superstitious or religious, and like most skeptics is a bit of a grouch about it. He wants to set up one of the trendiest cafes in Kathmandu (Nepal).

One day while scouting for locations, Tenzin stumbles upon an old abandoned temple and promptly goes about removing things and taking pictures. This horrifies his best friend Jachung (Tulku Kunzang), a conservative, who tells him that the place is “the womb of the goddess” and as such should never be disturbed. Tenzin snickers.

Soon a series of phantasms upends the stability of Tenzin’s world. It begins with a vision of a young girl in a field of flowers followed by the chilling specter of his long-dead sister cleaning his kitchen.

When Jachung warns him “This could be a bad omen” and that he should at once seek a Buddhist monk oracle, Tenzin shrugs him off with a snort. “You know those monks are just after your money.” Jachung decides to bring the oracle to him anyway.

When the dark shades wearing and Google worshipping oracle with a penchant for good coffee (Blue Mountain and Mocha being his favorites) informs Tenzin, rather in an offhand way, that his visions were signs of his imminent death and that in fact he had only seven days to live, the incredulous Tenzin brushes him away.

But apparitions refuse to go. Until at last, beset with mounting fear and paranoia, Tenzin gives in to his friend to see the strange oracle again.

The oracle tells Tenzin that the only way to avert his fatal prophecy was to seek a peerless albeit an elusive lady manifest on earth known as a dakini. He directs him to a cranky old master sage for more information on the subject. The master sage, in turn, supply Tenzin with tips and ritual gestures to aid him on his journey.

‘A way to see the flaw as the truth’

The search, a problem Tenzin must solve, form the dramatic heart of the film. How will he find the ambiguous dakini? Will he find one? These questions are answered with equal measures of wit and sublimity.

Khyentse Norbu lets the story unfold in a slow, poetic pace. Contemplation is given ample time in the form of long pauses between dialogues, phantasmic riverbanks and curiosities that Tenzin encounters as he rides his motor bike across the narrow streets of Kathmandu.

The newcomer Tsering Tashi as the main protagonist Tenzin says so much without saying much, turning quiet moments of reflection and desperation into something rich and wonderful.

But it isn’t until he meets the unconventional monk oracle and the raspy old sage (the master of the Left-Hand Lineage) that the film finds its lyrical voice and indeed its springboard for its playful and subtle, yet not so playful and subtle, messages.

The monk oracle, played deliciously by newcomer Ngawang Tenzin, is a total opposite of what most of us imagine a monk to be, or want a monk to be, which is of serene in demeanor and of decorous in attire and manner, much like a zen monk.

Sporting dark circular shades, red headphones, iPad, his maroon robe worn way above his ankles to show off a pair of black leather boots, rosary and holy threads tied around his wrists like a rockstar, Khyentse Norbu’s monk in the film looks like he might fancy a drive to a Paris couture show than to a monastery.

What comes out of his mouth is elliptical, designed to confound and provoke and, in our Tenzin’s case, infuriate. Tenzin: “I don’t know if I am dreaming or not. Maybe it’s just my imagination.” Monk: “What’s the difference? Anyway, you’ll die soon.”

Or when he tells a baffled Tenzin that seeking out the evasive dakini was the only way to climb out from his misery. “This is a special method. A way to see the flaw as the truth. And a way to see problems as the solution.”

The monk oracle might as well be Khyentse Norbu’s alter ego. And he seems to be doing a lot more than poke fun at our morality and perception and at our attachment to our transitory bodies and selves, and at our laughable aversion to incontrovertible truths such as the impermanence of things.

But all that poking fun is not merely for poking fun’s sake. Its aesthetic splendors are tethered to an exalted purpose, which is to shine the light of the sacred on our foggy and fast moving reality.

The cantankerous master sage with a gift for wry sarcasm is an emblem of Tibetan mysticism, played to near perfection by Orgyen Tobgyal Rinpoche. “Oh, you again,” he tells Tenzin. “So annoying!” Or when Tenzin tells him he has only seven days to live, he responds dryly: “If everyone believed they had only seven days to live, the world would be peaceful.”

His grumpy persona, however, belie his wisdom. It was by design that he sends Tenzin on his spiritual journey, to open up his senses to the refreshment of impermanence, to the beauty of impermanence, to its infinite wonder and possibilities.

‘Cucurrucucú paloma’

There are delightful moments of romantic comedy as when the master sage and the monk feed Tenzin with an assortment of secret dakini signals and pointers and Tenzin, as he watches and listens to them, is visibly torn between his loathing for superstitions and his fear of but what if. What if this is just an elaborate ruse? But, what if it is not?

Belief is at the centre of the film. But it doesn’t come out preachy like other spiritually minded films. If anything, the film shines light.

Dakini, a divine feminine energy in Tibetan Buddhism, whose presence in the world is both the film’s overt subject and the source of its mystery, is used to convey, in the most subtle way a film can on the subject, the significance of belief and magic in our lives.

In many ways, the film is Khyentse Norbu’s nostalgia for the vanishing world of this magical aspect of Tibetan Buddhism. A world of magic diminished in the face of the all too powerful world of science and rationalism. But a world which the film says, is nonetheless accessible to us if only we keep an open heart.

Aiding to convey the film’s many layers of meaning is the masterful Taiwanese cinematographer Mark Lee Ping Bing (In The Mood For Love, Renoir) who is known to work with natural lights. He doesn’t disappoint.

The slow tracking shots of the saturated river banks, the long stationary shots of the insides of an enlightened master sage’s home, the kinetic handheld shots of the streets illustrating Tenzin’s turmoil, are all employed with elegance and charm to help coax Khyentse Norbu’s vision into vivid cinematic reality. Almost every frame is an expressive photograph worth putting in an actual frame and hanging on the wall.

The film flows to equally sublime music. ‘Cucurrucucú paloma’ a beautiful, haunting song from Mexico captures the turbulent state of Tenzin even if you don’t understand the lyrics. The duet scene between Tenzin and his mother, where on the last day of his prophesied death he goes to meet her, is especially nostalgic and uplifting.

You can walk away with a thousand meanings. Watching the film is like being held up by an enlightened sage from the mountain, who grips you with a mystical and life-altering message in his tale. It’s an exquisite return to cinema for Khyentse Norbu and one of his best.

Contributed by Kencho Wangdi (Bonz)

The writer is a former editor of Kuensel and can be reached @bonzk on Instagram