Jigme Wangchuk

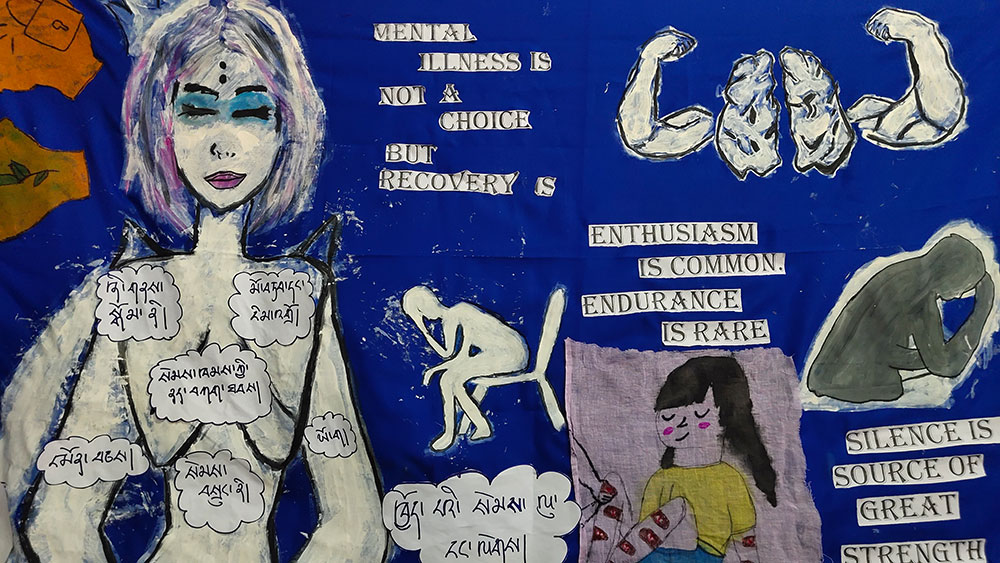

Mental illness is not, never has been, and never will be a choice,” Said Natalie Esarey, a Thought Catalog journalist, in an article titled Mental Illness Is Not A Choice — But Recovery Is. “In the same way that no one would wake up one day and choose to have cancer or diabetes, no one would wake up and decide they wanted to be depressed, anxious, bipolar, schizophrenic, suffer from an eating disorder … But no matter which way you shape or turn the hell that is being mentally ill—one thing remains. And that is this; it is NOT a choice.”

On Tuesday, September 21, the Media Club of Yangchenphug Higher Secondary School in Thimphu was organising a banner competition themed “Develop Mental Toughness—‘Your Mental Health, Your Priority’”.

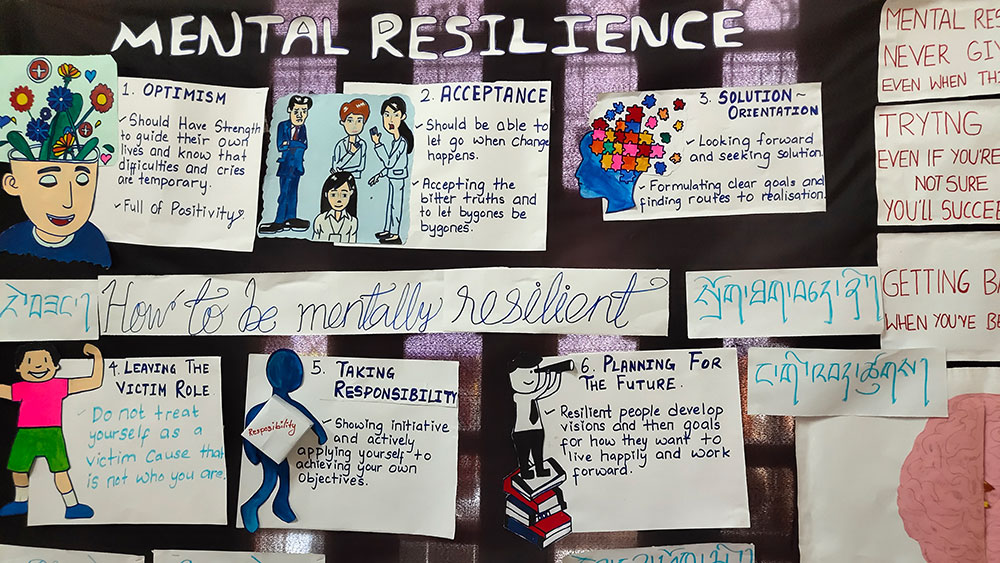

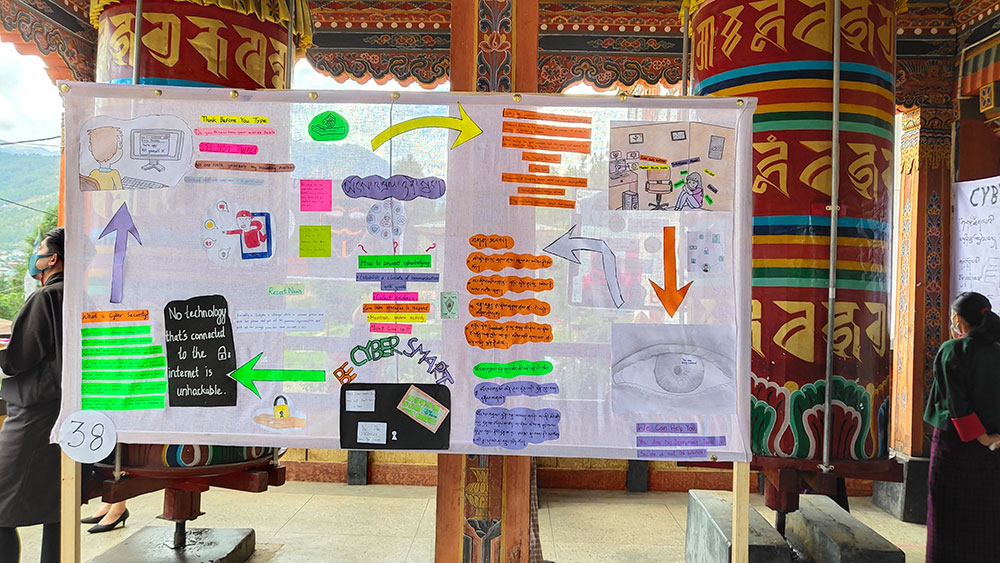

Close to 40 banners on cyber security and mental resilience were put up on the wall. Some were artfully hung between the massive prayer wheels at the school’s lhakhang. Information and designs were put together so masterfully that judges had a hard time choosing the best among the banners. Such meeting and marriage of creativity and exuberance!

But the best was yet to come. Each student who walked the audience from outside and their peers through the banners did it with passion and confidence rarely seen in high school students that their own teachers were left amazed and inspired. You could see the approving smile and pride beaming on the face of Yesh B Ghalley, the school’s principal.

Bhutan is witnessing a rapid rise of conflict among children and their parents which gives rise to stress. These conflicts, psychiatrist Dr D K Nirola in his article in Kuensel titled Parents-children conflict: A reflection, “are leading to various behaviour issues in children and young adults. Youth are seen to be frustrated, depressed, anxious and at times outrightly violent against themselves.”

In his analysis, young people in the country seem to be increasingly losing psychological resilience. “They don’t seem to be able to accept anything which is beyond their liking. They seem to be all the time rebellious against parents, teachers and society at large. We are facing a big challenge of frustrated and angry new generation.”

A psychological anthropological study could come in handy. But even as we recognise the need for such a crucial research, we seem to not have the capacity to initiate or undertake the task. A study has found that even though some measures are put in place to battle mental illness, suicide is already among the six biggest killers in the country. According to Suicide Prevention in Bhutan — A Five-Year Action Plan 2018-2023, for every 1.5 deaths by suicide there is one suicide attempt recorded.

Since the Ministry of Health began recording deaths by suicide in 2013, there has been an average of 73 suicides cases per year, or six suicide death a month. And Bhutan’s 12 per 100,000 completed suicide rate is higher than the global average of 11.4 percent per 100,000 population per year. More than 56 percent of suicide occurs among 18-35 year old, the most productive age group.

Showing the visitors around, Deepa Rai of XII Arts C, said: “Such events are very important to help us open up and talk about our stress and mental well-being.”

Deepa’s friend Tsheyang Choden of XII Science D agrees. She said that early interventions are critically necessary: “Schools should have more experienced counsellors. We might have any number of counsellors but if they can’t address the needs of the children, all our efforts to fight the growing mental health issues in the count could go in vain. At a time when parents and teachers prioritise children’s academic excellence and achievements above all else, we need to build a strong support system to raise resilient children.”

Stress can come when families are always on the go. With rapid development and change, Bhutanese families are increasingly living busier and overscheduled lives. In such environments, mental health experts say that children and teens need to develop strengths, should be equipped with skills to cope and recover from hardships. Resilience in this sense is being prepared to face the challenges on the way—to bounce back and sail through.

“Schools should have mental health class, the lack of which I feel is giving rise to an alarming number of mental cases in the country,” said XII Commerce B student, Sonam Yoezer. “Children, youth in the main, could otherwise become less and less resilient. And that is both a sad and serious social malady.”

For Tandin Samphel of XII Science C, organising the programme itself helped them release their stress and tension.

“Breaking the taboo associated with mental health is critically important, now more than ever when children and adults alike are exposed to and bombarded with so much information,” said Karma Tashi of XII Science B. “There is a need for us, particularly children, to build resilience to navigate through the complex maze of pressure and expectations. Parents, teachers and elders have a huge role to play.”

When the last bell tolls and children scuttle out of class to catch their bus home, Drawn from Natalie Esarey’s 2017 article, the theme of the banner brings us back to the powerful statement: Mental Illness Is Not A Choice — But Recovery Is. What this means is that recovery could sometimes take time but there should always be a conscious decision to fight and not be a victim of mental illness.

And there, a school can do so much more to guide, educate and raise resilient children.

“That’s exactly what we are trying to do here today in our small ways,” says Kusum Latha Sharma, head of the school’s media department.