Tribute to Richard C. Blum

“We’ve got to restore the monastic school. If we are going to bring this area back to life, it has to start with temples, the monasteries, and the monastic school.” This is how Raja Jigme Dorji Palbar Bista (1930-2016), the King of Mustang convinced Richard C. Blum to help save the dying soul of Mustang.

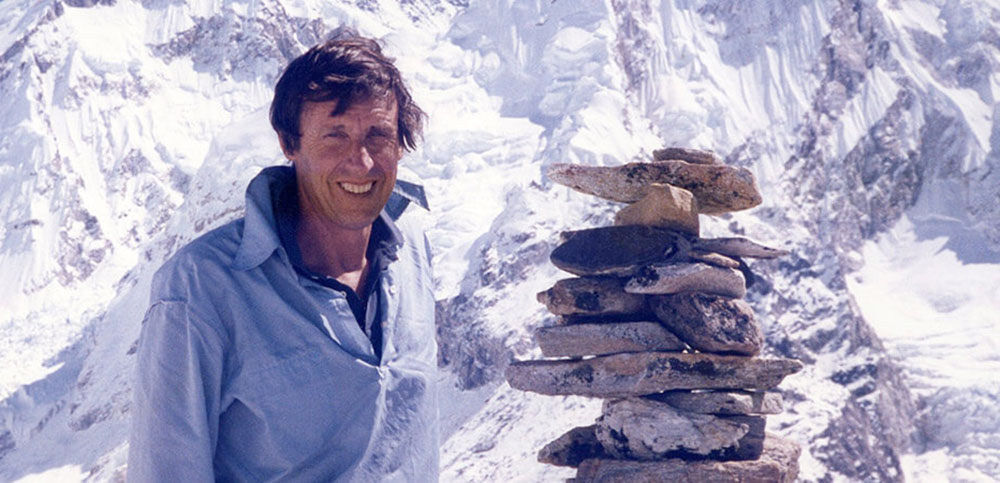

In 1968, the American philanthropist visited Nepal to trek. Enthralled by the beauty of the Himalayas and the exceptional people that lived in its fold, his love for trekking turned into his lifelong passion for the Himalayas.

Impressed by the simple people of the Himalayas who practiced compassion and believed in good conduct for ever higher rebirth, in 1981 Richard set up the American Himalayan Foundation.

As its founder, he had the honour of meeting the King of Nepal several times. During his audiences with King Birendar Bir Bikram Shah, the American private business equity investor said that he made sure to petition that he be the first one to be officially allowed into Lo Manthang.

In 1964, Michel Peissel had already visited the forbidden land. The French ethnologist’s book “Mustang”, published in 1967, sparked Richard’s interest which was further fuelled by the fact that Mustang was off limits.

Driven by his motto, “Nothing Ventured, Nothing Gained,” his persistence bore fruit. In late 1991, he finally received the green signal. This was just a few months before Nepal officially opened the gates of the forbidden kingdom of Mustang to limited tourists.

Back then, with no motor roads, Richard and his daughter along with his business partner ventured into the little-known kingdom. They trekked and rode on horseback to cover the 50 miles of narrow steep trails and cross high mountain passes to reach the walled city of Lo Manthang.

Richard covered this interesting adventure in his book, “An Accident of Geography,” (2016). Written with increasing sense of urgency with the aim to raise awareness and lift living standards in the world’s poorest communities, he illustrates his meeting with Raja Jigme.

He describes the 60-year-old sovereign as sincerely and deeply concerned about his dying community. When the king confessed that he saw himself as another in a long line of monarchs (26 kings) who allowed things to deteriorate, Richard’s commitment to help was sealed.

While in Mustang, Richard was fascinated with the country’s rich history and was amazed to hear the story of the two great monasteries of Thubchen and Jampa.

In his book, Richard wrote that, Mustang once prospered as a trade centre where salt from the dead lakes in Tibet was bartered for wool, grain and spices from India. He mentions that the local merchants tapped their growing wealth to build the two great monasteries in appreciation of their good fortune. With surplus funds they hired the best Newari artisans from Kathmandu and filled these monasteries with sculptures and exquisite, vibrant paintings of deities and mandalas.

Both these monasteries were architectural triumphs and had anchored the traditions and culture of the people of Lo Manthang for several centuries and endured as the spiritual heart of the Loba culture.

However, their good fortune did not last. In the beginning of the 18th century, local merchants’ wealth began to wane. Lo Manthang’s position as a trade and culture centre began to decline. This was primarily because of the shift of the trade routes caused by hostilities in the frontier region and also because of the more efficient trading practices of better educated tribes downstream. After the 1950s, with increasing frontier tensions, Mustang became even further isolated.

As a result, decades later, the temples became neglected and had already started crumbling when Richard first saw them. Richard in his book describes the falling roofs of the temples, the soiled murals covered in soot and grime from the butter lamps, and walls cracked by earthquakes.

Richard thought it would be a shame to lose such priceless cultural treasures, but he himself had no experience in restorations. His focus was on schools, health care and elder care.

Richard said that after giving some thought to the Raja Jigme’s impassioned words he was convinced. The Raja’s argument was that without cultural identity, the community has nothing to hold it together, nothing to build upon and it was culture that was the soul of its community and the monasteries would be the wellspring for reviving the Buddhist traditions and cultural identity of Mustang.

While the Raja heard stories passed down from his ancestors about fabulous paintings, he really did not know what would be found if a conservation project was mounted.

Despite the numerous challenges, AHF restored the monastery to its former glory. After 20 years, the Italian maestro, Luigi Fieni not only meticulously restored the 15th century wall paintings but also trained over a hundred local artisans.

Richard was witty and funny. As a close friend of the 14 Dalai Lama, he often had to introduce His Holiness during talks. He would say, “We know who his Holiness was in his last life. He was the Thirteenth Dalai Lama. What we don’t know is who I was in my last life. I must have done something really terrible to be reincarnated as an investment banker.”

Bhutan

Richard visited Bhutan seven times, firstly in the 1970s, and then in 1987, 2005, 2013, 2017, 2018 and 2019. Inspired by the restoration of the temples of Mustang, in 2002 his Foundation contributed generously to restoration of Buli monastery in Bumthang. The first of its kind project, started in 2002 was led by another world-renowned conservation architect John Sanday.

When Richard visited Bhutan with his daughter Heidi in 2018, he was re-smitten by the people and its extraordinary leadership. He visited again the following year. By then, he was frail but he stoically endured the long-distance flights. He squeezed himself into the helicopter to fly to Buli and Tsirang so as to see for himself the past and potential projects.

Impressed with the Tarayana housing project to alleviate poverty, he offered generously to the Foundation to build more homes and pledged even more. By doing so, he gave thousands of Bhutanese new lease of life. He supported the construction of public facilities in Singye Dzong to make the pilgrims stay more comfortable.

Although Raja Jigme passed away at the age of 86 in 2016, his restored monasteries in Mustang have become the soul of the community. Richard’s book has more moving and inspiring stories with solid examples of how to fight poverty. In 2019, he had accepted and was looking forward to launch and talk about his book, “An Accident by Geography,” at the Bhutan Echoes Literary Festival. His last words in Bhutan were, “Finally, I discovered that I was a yak in the Himalayas in my previous life.” After indulging for more than 50 years of his life in his two greatest passions; the Himalayas and Asia, on 27 February 2022, this champion of the unseen and unheard passed away at his San Francisco home, aged 86. Yesterday, on 2 March, on behalf of the Bhutanese, the Tarayana Foundation offered thousand butter lamps in the ancient Semtokha Dzong, holy site of Singye Dzong and Bodhgaya and scores of monks prayed for the swift rebirth of Richard in the Himalayas.

Contributed by

Tshering Tashi