Younten Tshedup

Having a physically robust body does not always correspond with having a healthy body. If records with the Jigme Dorji Wangchuck National Referral Hospital (JDWNRH) are any indication, a large number of Bhutanese are sick.

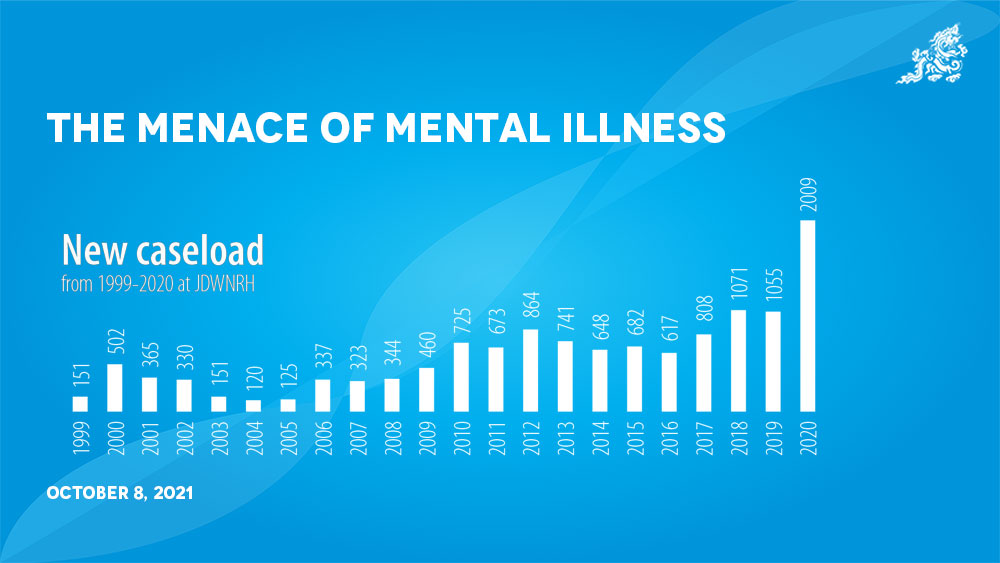

Over the past two decades, the JDWNRH in Thimphu has been recording an increasing number of mental illness cases every year. The number of mental illness cases hit a record high of 2,009 new cases last year, triggered mainly by the Covid-19 pandemic.

One of the senior-most psychiatrists in the country, Dr Damber K Nirola said that the pandemic-induced lockdowns and quarantine practises resulted in a drastic increase in mental illness last year.

However, he said that as an overall trend, the graph of new mental illness cases in the country was increasing due to multiple factors.

He said that one of the main reasons for the increase was because people came forward seeking medical intervention for mental health-related problems. This, he said, is because of the extensive awareness and advocacy programmes held on mental health over the years. “Through various mediums, people have been educated on the possible signs and symptoms that might signify mental illness. That is why we see more people coming forward if they experience any of the symptoms.”

Childhood adverse events, he said, are another factor triggering more mental health-related problems in the country. “We are seeing more reported sexual abuse cases among children today, which contributes to mental illness as they grow up.”

Dr Nirola said that the younger generation today can be emotionally unstable and that their psychological resilience is ‘very poor’. “They get easily frustrated when things don’t go their way and, in the process, take drastic steps including suicide attempts.”

He said: “Young people think they are entitled to emotion, meaning they think they have to be loved unconditionally, and they have to be provided for unconditionally. The moment their demands are not met, they feel frustrated leading to anxiety and other mental problems.” Environmental and genetic factors are other causes for many types of mental illness.

The competitive nature of society also instigates mental health problems, said the psychiatrist. He said the race to be successful in life starting with school, to perform better in academics, getting a good, high-earning job, can be opposed by the realities of life, further inciting frustration and the feeling of hopelessness in people.

Dr Nirola said that some of the emerging mental health issues in the country included substance abuse among youth, borderline personality disorder, repeated self-harm, and an increase in the risk of suicides.

He said that some 20 years ago, the most common mental illness reported to the hospitals was depression. “However, today we see more anxiety and panic disorders among our people,” he said, adding that cases of schizophrenia were also on the rise. “If a person is suffering from schizophrenia, there is a high possibility that he or she will become disabled throughout their lives.”

The psychiatrist said that some mental illnesses are preventable and those suffering from the illnesses can return to good health, provided they receive timely intervention in the form of medication and counselling. However, one of the biggest challenges faced by the country on the mental health front is human resources.

While mental health-related cases have been steadily increasing in the country, Bhutan currently has only two psychiatrists, both stationed at JDWNRH. There are no clinical psychologists or occupational therapists. “The reason we have not been able to fill this gap rapidly is because producing psychiatrists is not easy,” said Dr Nirola.

He said that, unlike other fields, undergoing a post-graduate degree in medicine requires at least four years of study. “Many countries have strict screening procedures to take in candidates. Our university, Khesar Gyalpo University of Medical Sciences of Bhutan (KGUMSB), cannot take more than one psychiatry candidate every two years, given the limited teaching faculty.”

There are currently three doctors undergoing a post-graduate degree in psychiatry at KGUMSB in Thimphu. By July of next year, the first psychiatrist will graduate from the university.

Two more doctors are undergoing a similar programme abroad and are expected to complete their course within the next four years.

Edited by Tshering Palden