Ever since I brought Tibetan calligraphy art into the limelight by creating a world record for the longest calligraphy scroll in the world (165 metres) in 2010, I have been experimenting with Tibetan calligraphy art, creating new works, posting regularly on social media, exhibiting, talking, sharing and learning.

I don’t know how much I could inspire and encourage people around me. Still, I can say with certainty that the imagination of promoting Tibetan calligraphy as an art, besides acquiring the skill of beautiful writing, has caught like a wildfire in Tibet. In 2017, they declared April 30 as the Annual National Day of Calligraphy to celebrate four vowels and 30 consonants (4.30).

Calligraphy means beautiful writing. They call it ‘shufan,’ a way of writing. In China, and from a very early period, calligraphy was considered not just a form of decorative art; instead, it was viewed as the top visual art form, more valued than painting and sculpture, and ranked alongside poetry.

This Chinese calligraphy and poetry found international recognition as one of the most beautiful traditional arts, with dedicated connoisseurs, and more people became its collectors. The art became somewhat standardised and developed its own peculiar conventions.

Thönmi Sambhota, one of the most capable ministers of the Tibetan rulers in the 7th century, was sent to India to develop an alphabet suitable for the Tibetan language. Thönmi derived the new script from the Devanagari script used in India.

Throughout the centuries, our ancestors have developed at least 100 different styles of writing, broadly categorised as Uchen, Umed, and Druktsa styles. However, Tibet devoted its entire state machinery and resources of the kingdom in developing the Buddhist philosophy of ‘science of the mind’ to benefit sentient beings.

Some 70,000 pages of Kangyur (‘Translated Words of Buddha) and 161,800 pages of Tengyur (Translated Treatises) were translated from Sanskrit to Tibetan. From a secular perspective, Tibet produced many great scholars who wrote poetry and other literature on philosophy, metaphysics, medicine, and astro-science, with only one objective in mind: benefiting others.

Writings of great scholars like Je Tsongkhapa, songs of Milarepa, compositions by Sakya and Nyingma masters are relevant and are studied in all the monasteries even to this day.

(Je Tsonkhapa (1357 to 1419) is a great Buddhist scholar, whose works laid the foundation of the Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism. Milarepa (circa 1028 to 1111) is the venerable Tibetan siddha, or “Perfected Master”, and is the most accomplished pupil of Marpa, the “Great Translator”, who worked on original Sanskrit Buddhist texts.)

Unfortunately, anything other than spiritual practice was neglected, such as art and entertainment.

What is Art?

Art is a visual or vocal expression of the innate feeling of an artist from their heart, unstructured, boundless and spontaneous. At the same time, craft refers to an activity, which involves creating tangible objects with the use of hands and the brain.

Tibetan calligraphy is a skill that can be practiced, perfected, and reproduced. Yig tsal, or the art of writing, cannot be reproduced. It is an art. Yig tsal is equivalent to ‘Shodo’ of Japan and ‘Shufan’ of China.

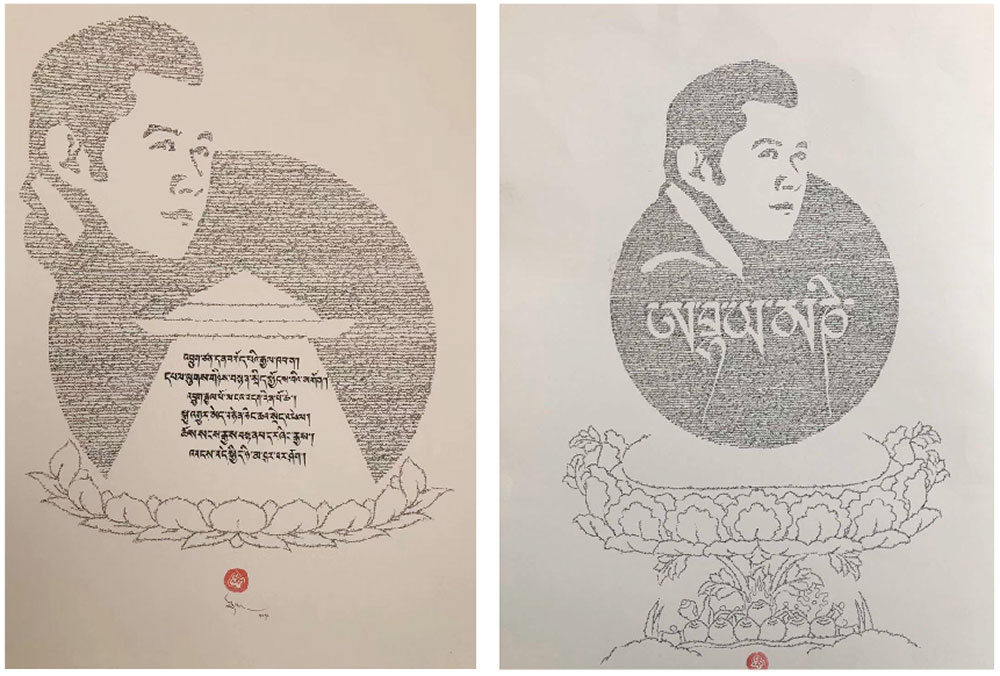

I use ‘kyug style’, a form of a cursive script of the central Tibet region for calligraphy art.

The cursive script has more flexibility, for it only maintains the essence of each character and expresses more personal exertion. Therefore, its value lies in appreciation, of beholding, more than practicality. At the same time, the running hand makes full use of connecting lines between two strokes.

Watching art is also an art. The process of creating beautiful art, from conceiving an idea to the final expression on paper, is a profound meditative process. Art is a visual expression of the sound of the heart of an artist, and if the ‘tsa lung’, perhaps called the ‘Chi’ energy of an artist, is balanced and steady, the resultant visual art becomes a masterpiece.

Some say ‘calligraphy speaks’. I have created more than 200 styles of calligraphy art, and often, friends ask me: “How did you get so many ideas?” I say lightly that Guru Rinpoche has opened his treasure trove to me!

But honestly speaking, I have asked the same question to myself again and again. And only now, am I beginning to learn the answer. My experience is that I do not get two ideas at the same time. Only when I complete executing one work, put my seal on it, that there is a blank or emptiness.

Slowly, the next idea takes shape. I know that the void or the blank is vast, like an ocean. It indeed is the treasure trove of wisdom, limitless, and like a child with a small cup in hand, I stand at the shore of this ocean, not strong enough to go nearer and fetch water but confident that when the wind gushes, a drop will fall into my cup. These droplets are the result of my collected works.

When I shared my personal experience with my Spiritual Master, Tsoknyi Rinpoche, he beautifully explained the following, which awakened my consciousness and put my thoughts into proper perspective.

I would call this a Calligrapher’s Journey into the nature of mind.

Rinpoche says that there are four types of letters:

• A letter that rests on the natural state of mind

• A letter on ‘nadi’ (རྩ) energy or ‘tsa’ that moves with ‘prana’ ( རླུང་), or the wind energy in the physical body

• A letter that produces sound with the result of the movement of that wind energy

• The final expression of the artist is in the form of calligraphy.

We believe that our ‘nature of mind’ is primordially pure, clear, and vast as the sky. It also holds wisdom that can dispel ignorance. A letter is a medium to contact and to impart information, and dispel ignorance.

Sacred Journey

Let us look at how this journey from ‘nature of mind’ to the visual form on the paper takes place.

The artist sits down in a state of calmness and tries to look within the mind’s nature. He picks up a droplet from the ocean of wisdom. He then brings it to his own physical body and evokes the letter energy on his ‘tsa’ (རྩ) or the wind energy or the ‘lung’ ( རླུང་), whose nature is always moving, takes the letter on ‘tsa’ and converts it into a letter of sound.

By using the necessary tools, such as brush, ink stick, paper, and ink slab, which the Chinese calligraphy masters call the ‘four treasures of study,’ and converts the letter of sound into the form of a letter, called calligraphy. This way, he expresses the inner world in an aesthetic sense for others to behold.

It is almost a sacred journey that few people can appreciate. It is an art to look at art, and only those who understand can fully marvel at such works.

Similarly, when you have such art on your wall, you can study it carefully, the strength of strokes, the darker and lighter shades of inks, the writing flow, and most importantly, the message it is trying to convey.

The viewer can retrace the calligraphy art in the form of its root, sound, letter on your ‘tsa lung’ and finally to the vastness, pureness of the nature of mind.

Buddhism

Our masters have, over the centuries, introduced varieties of skillful means to teach Buddhism by introducing many kinds of deities by way of statues and thankas (spiritual scrolls), each for wealth, knowledge, strength, compassion and long life, etc. Ultimately all these deities dissolve into your heart, and just like you put a drop of water into oceans, it becomes one with the ocean, inseparable.

Therefore, practicing calligraphy art is also a skillful means to see your nature of mind, which is the ultimate goal of all Buddhist teachings. It is the best tool to practice mindfulness besides promoting a unique traditional art. It is a gem that we ignored. I hope the next generation will have some sense of what I am trying to say. Yet, I would still say that to watch art is also an art.

Contributed by

Jamyang Dorjee

(The author is a senior ideologue-practitioner of Tibetan calligraphy, and has developed explicit varieties of it, exhibited around the world. He is based in Gangtok, Sikkim, India. Email: jamyangitsn@gmail.com