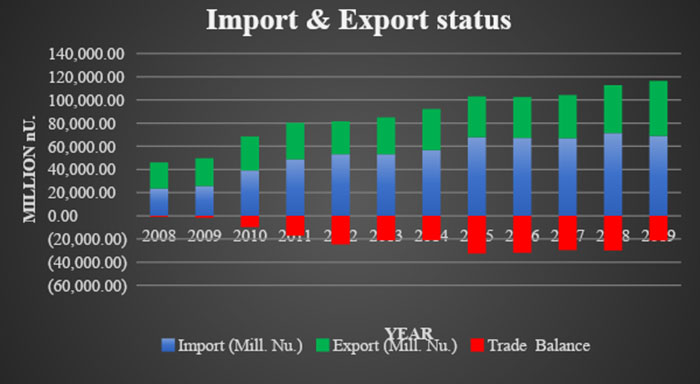

Over the last ten years, our exports have doubled, so have the imports; however, the quantum differs substantially. For instance, in 2019 alone, we spent Nu 68.91 billion for imports while we earned just Nu 47.48 billion from exports leaving massive Nu 21.42 billion as the “Trade Imbalance”. However, it may be noted that the trade imbalance in 2019 had fallen by almost 28% compared to 2018, primarily due to additional revenue on account of the 720MW Mangdechhu hydropower project and the enhanced export of boulders.

If we are to narrow the import-export gap, it is imperative we enhance exports and minimize imports or promote substitutions through domestic production.

As per trade statistics maintained by DoT, MoEA, during the fiscal year 2018-19, Bhutan imported goods from 64 countries. The topmost imported items were petroleum products worth Nu 10.27bn, ferrous products – Nu 3.143bn, vehicles- Nu 3.93bn, rice products- Nu 1.66bn, and wood charcoals worth Nu 1.88bn. During the same year, we exported to 45 countries and the most exported items were electricity- Nu 16.24bn, Ferrosilicon-Nu 9.78bn; boulders- Nu 4.98bn; gravels & pebbles- Nu 1.82bn; cement- Nu 1.19bn).

From the above lists, it is clear which items need to be prioritised for exports and what to be curtailed in imports. In the export category, we must explore alternative sources for electricity generation so that more electricity from some hydropower projects could be displaced for export. This is becoming even more relevant as export tariffs earn much better. For instance, a unit of energy from Mangdechhu hydropower project displaced for export will garner Nu 4.12/unit which offers an opportunity to promote any other electricity generation alternatives that can be developed below Nu 4.12 per unit. The other items to consider are ferrosilicon, boulder, and cement as Dungsam cement plant still has the potential to produce more without more capital inputs.

On the other hand, we must take immediate and drastic measures to minimize the import of vehicles and petroleum products. As per records with Road Safety and Transport Authority (RSTA), there are 105,649 vehicles or 1 for every 7 people in the country as of July 2020. This includes 6,702 vehicles imported during the FY 2019-20.

In 2019 alone, more than Rs 10.27 billion was spent on fossil fuel imports. One immediate intervention is to expedite promotion of Electric Vehicles (EVs)/hybrids and associated infrastructure to motivate, especially the government/public offices/institutions to opt for such alternatives. For instance, a Hyundai Tucson comparable EV driven alternative (Hyundai Kona) comes for an upfront cost of around Nu 2.60 million, closer to that of Nu 2 million for Hyundai Tucson. Besides this marginal upfront cost difference, the Kona will be more advantageous with minimal operational and maintenance costs. For example, the KONA comes with a battery which will consume just 39.2kWh of energy with which it can travel 452 kilometres costing just Nu 198 (Nu 5.06 per kWh). However, for the same distance, a Tucson would consume around 45 litres of diesel which translates to more than Nu 2,300, so there is a huge operational costs difference.

The other items to be considered for domestic production are rice and charcoal, which should not entail much technological complexity and raw material constraints.

While there could be many other options, these are suggestions to help relevant stakeholders/agencies/individuals to prioritise and consider more focused interventions to facilitate and promote these sectors.

Contributed by Passangyt, Thimphu

pyt.doe@gmail.com