Choki Wangmo

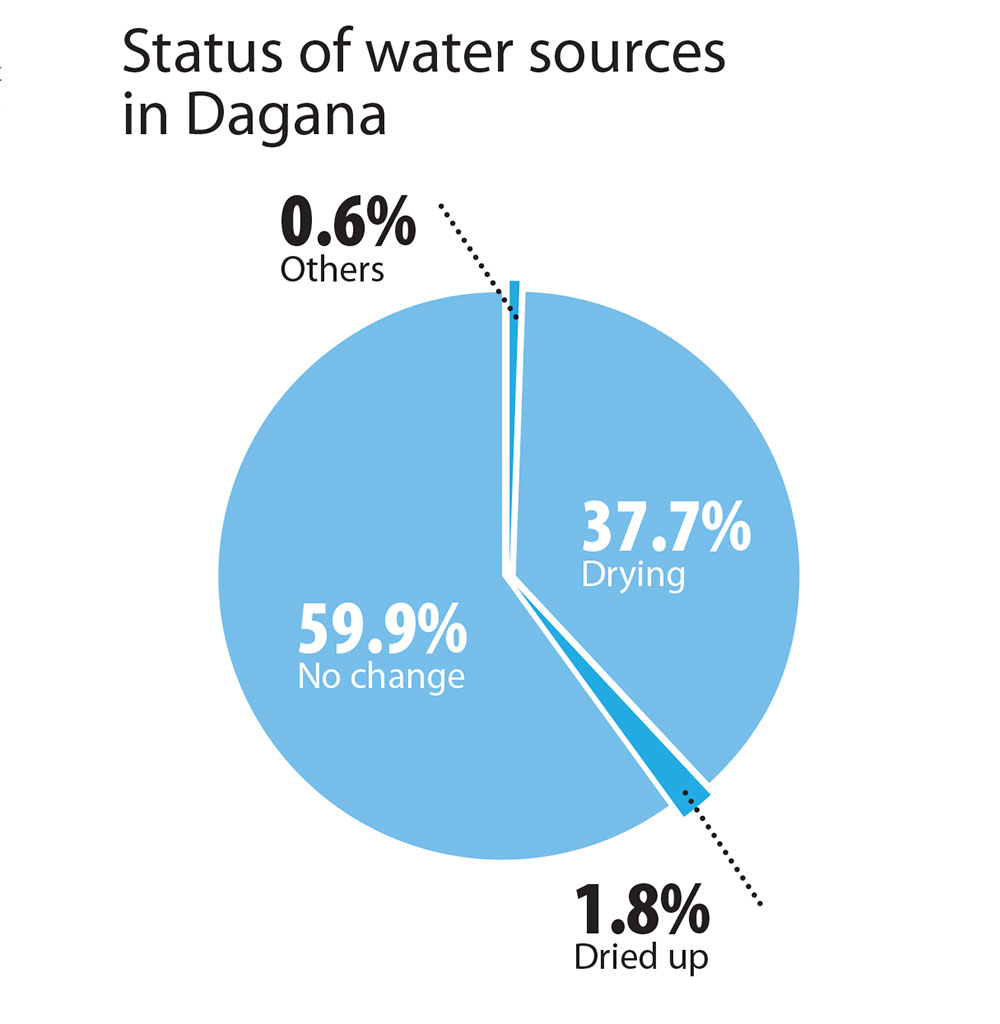

A large number of water sources are drying in Dagana.

A total of 281 water sources—271 are drying and 13 has already dried up, according to the water sources assessment carried out by the Watershed Management Division in December 2021.

Of the 12 gewogs, it was reported that all water sources in Tashiding are drying up, followed by Tsangkha (76). In some chiwogs in Gozhi, which has long reported severe cases of drinking and irrigation water shortage, 37 water sources are drying up.

Four water sources in Larjab, five in Kana, and one each in Gesarling, Khebisa, Lhamoidzingkha, and Nichula gewogs have reportedly dried up. Seven watersheds in the dzongkhag are in degraded state, five in pristine state, and nine are reported to be normal.

People say that climate change and forest degradation have accelerated the drying process.

Most of the people in the dzongkhag depend on spring water, followed by streams, and rivers for drinking and irrigation.

Of the 7399 water sources across the country, Dagana has 719.

Where is the gap?

Bhutan has one of the highest per capita availability of water in the world. Official figures show that Bhutan generates about 70,500 million m3 per annum, meaning each Bhutanese should ideally have access to about 94,500 m3 per person per year.

Experts say poor governance and management are some of the underlying causes for water shortage in the country. Disturbances at the catchment, change in land use pattern, forest fires, disturbance of natural vegetation, and climate change could be contributing to dwindling water availability.

Almost 99.5 percent of Bhutanese have access to improved water sources, yet only 63 percent have 24-hour access to drinking water.

Locals in Dagana have often reported challenges in drawing water from the available sources.

For instance, the 12km irrigation canal in Drujeygang, built at the cost of Nu 16.9 million, remains idle today.

Further, rainfall patterns have changed from long monsoon cycles to erratic downpours and this is not giving enough rain to recharge to the aquifers, which are a critical component of watersheds.

Reports show that 34 percent of water is lost along distribution networks. Irregularities in water distribution networks such as illegal tapping, water connection bypassing water meter, approval of water connection from transmission lines, and diversion of water supply are rampant.

Impact

Drinking water shortage in the dzongkhag has forced farmers to look for alternative sources of income in other sectors. It has even forced people to migrate to other places.

For example, as there were no interventions even after decades of water shortage in Geserling, residents said that goongtongs had increased in the chiwogs as young people from the gewog migrate to towns, looking for income opportunities.

Most of the 30-acre wetland in Geserling is left fallow.

Students in particular are affected by the lack of water. Some raised health concerns.

The situation has become dire for half of the 40 households in the Gozhi Toed chiwog. For two months in winter, the villagers do not have drinking water. The water sources at Chichibi and Jhorpokhori (four lakes) have dried up.

People hire pickup trucks to transport water, but this is becoming increasingly difficult for many farmers.

In Gelechhu, Tsangkha, residents are grappling with the severe impacts of water shortage.

Before interventions, due to lack of irrigation water, farmers in Norbuling, could not grow vegetables and crops on a commercial scale. Most of the 69,867 acres of dryland, 0.78 acres of wetland, and 2.303 acres of orchard that were left fallow.