Yangyel Lhaden

I attended my first United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change’s (UNFCCC) Conference of Parties (COP) at COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan, this November. For years, I have written stories on the environment, climate change, and conservation. But this was my first experience with climate diplomacy—a stage where world leaders gather each year to reaffirm commitments, explore new solutions, and stand in solidarity against the global challenge of climate change.

I thought I was prepared. I had done my homework—or so I believed. But within days, I realised how little I knew. The complexities of COP are overwhelming. It is a political chessboard where science meets economics, and negotiations attempt to bridge clashing ideologies. Achieving consensus? It is anything but simple.

But let’s rewind to the beginning—the Happy COP.

I boarded the shuttle bus on the first day of COP, the same one that would take us to the venue every day for the next two weeks. Delegates from around the world filled the bus, buzzing with energy, exchanging big smiles, and greeting each other with, “Happy COP!”

The delegate seated next to me turned and said it too: “Happy COP!” I have never heard the phrase before, but I joined in, saying it back. Why not? I was happy—excited, even. Like a curious child, I took in my surroundings, my eyes wandering, my ears already catching snippets of conversations.

As the bus pulled up to the sprawling Baku Olympic Stadium, I stepped into a sea of suits and dresses. Inside, the stadium had been transformed into a maze of meeting rooms, plenary halls, and food courts. Banners with bold slogans—UN Climate Change, COP29 Baku, Azerbaijan—hung everywhere, calling for urgent action on climate change in green colors.

Thousands of people moved with purpose, and I followed the crowd. Everyone seemed to know exactly where to go. Except me. As I wandered the endless hallways, a strange feeling crept in. I was not just lost in the stadium—I was lost mentally, emotionally. What was I supposed to do? Where was I supposed to start?

I decided to settle in the media centre to watch the opening plenary of COP. Bold remarks from the outgoing COP Presidency urged action before handing over to Azerbaijan’s COP President. Simon Stiell, UNFCCC’s Executive Secretary followed with a powerful call for unity which gave a sense of hope.

The first day ended on a positive note, with an agreement on a new climate finance goal and progress on operationalising Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, on carbon markets. Early in the conference, leaders from the Hindu Kush Himalaya region pledged bold regional action, emphasising the need for solidarity among vulnerable nations.

On the second day, the G-Zero initiative—a platform for carbon-neutral and carbon-negative nations—was launched, contributing to the sense of momentum. Bhutan had its own proud moment during the COP when the ongoing conference coincided with His Majesty The King’s inclusion in TIME’s 100 Climate Leaders, recognising his visionary leadership and commitment to a sustainable future.

But as the days passed, the initial optimism gave way to a sobering reality. Negotiations slowed, and countries like Argentina withdrew their negotiators. While discussions focused on financing for vulnerable nations and transitioning to green energy, I began to question: are voices from small nations like Bhutan, who lead by example, being heard?

Bhutan’s carbon-neutral status and commitment to the planet are extraordinary, yet these contributions seemed to go unnoticed in the larger arena. It felt as though the conference wasn’t designed to recognise such quiet leadership but instead revolved around larger powers negotiating gains.

I also began to notice something. The conversations I overheard at the venue, in meeting rooms, and during side events were not just about policies or politics—they were about people. Farmers in drought-stricken regions, mountain communities, families fleeing rising seas, and those living on the frontlines of climate change. What stood out was how economics, climate science, and politics intersected in these discussions. The challenge lay in finding solidarity to help those most affected, despite these divides.

Amid this, the venue itself was a spectacle of activity, with pavilions that ranged from modest to extravagant. Brazil’s pavilion, promoting Belem as the next COP host, was one of the most striking. I learned that setting up even a small pavilion costs at least USD 200,000. Bhutan didn’t have one this time, though it had debuted its first pavilion at COP28 in Dubai.

Pavilions offered free coffee, snacks, and spaces for casual meetings, drawing participants for brief stops. Meanwhile, at the food court, a simple coffee or quick meal cost upwards of USD 20. I later found out delegations also had to rent office space at the venue and Bhutan did not have one. Everything here seemed to come with a hefty price tag, making me wonder how small nations like Bhutan manage in this expensive arena.

Routinely, Bhutanese technical negotiators debriefed the progress of negotiations to the Head of Delegation, Secretary Karma Tshering of the Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources. Once, they gathered near a meeting hall, sitting cross-legged on the floor in true Bhutanese style. They shared a quick lunch of delicious home-cooked Bhutanese food with me—a reminder of the warmth and sense of community Bhutanese carry wherever we go.

The discussions were practical, focused on how each negotiation outcome could impact Bhutan. Secretary Karma Tshering repeatedly asked, “How will this help the country? What are the implications if this decision is taken?”

Bhutan’s negotiators were rarely seen in the public areas of the venue. They were hard at work behind closed doors, often sacrificing sleep to ensure they could bring something meaningful back home.

The negotiations, initially scheduled to conclude on Friday, November 22, extended until Sunday morning, dragging on for an additional 35 hours and 30 minutes. Negotiators remained at the venue throughout this extended period until the closing plenary. A key point of contention was the demand from developing nations for USD 1.3 trillion in climate finance, which was not met. Instead, developed nations committed to USD 300 billion, leaving many developing nations disappointed as they departed the conference.

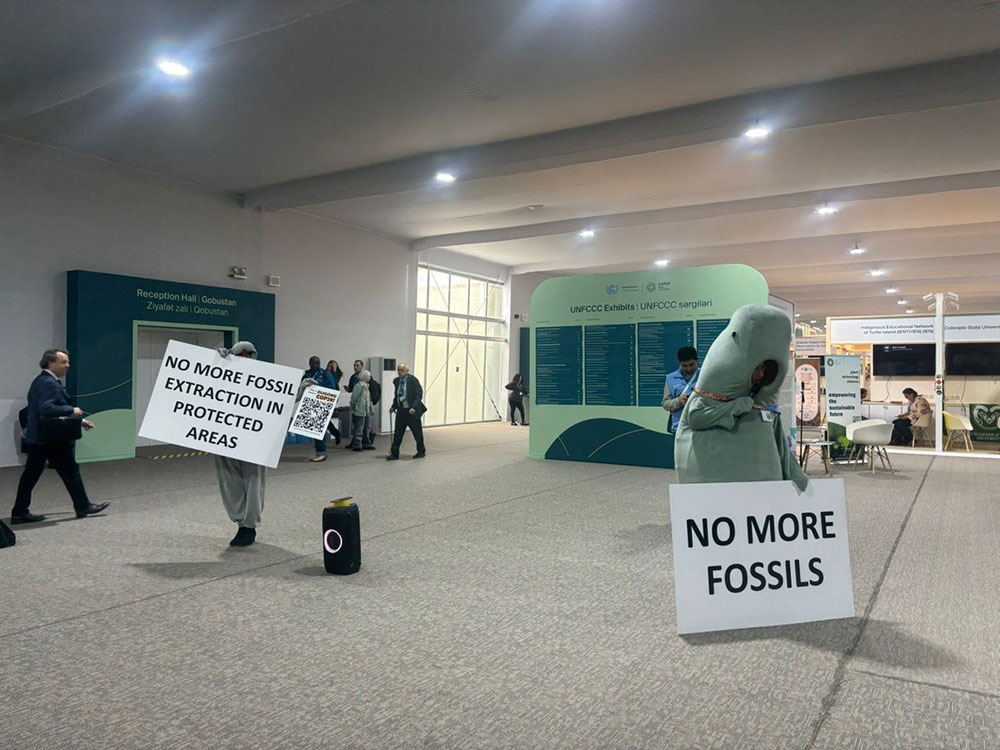

As I wrote my final story on Sunday before leaving Baku, Azerbaijan, I could not help but reflect on the irony. Baku, an oil-rich country hosting COP29, and the oil drills I saw outside the city. First, it was a small red one, but then, looking closer, I noticed vast stretches of land dotted with them—an unmistakable irony. While COP29 unfolded with calls to end fossil fuels and commit to renewable energy, these drills stood as a reminder of the challenges ahead.

Every year, developing nations leave these conferences disheartened, their calls for equitable support often unmet. Climate change is about “we,” yet where is the solidarity? Where is the hope?