Thinley Namgay

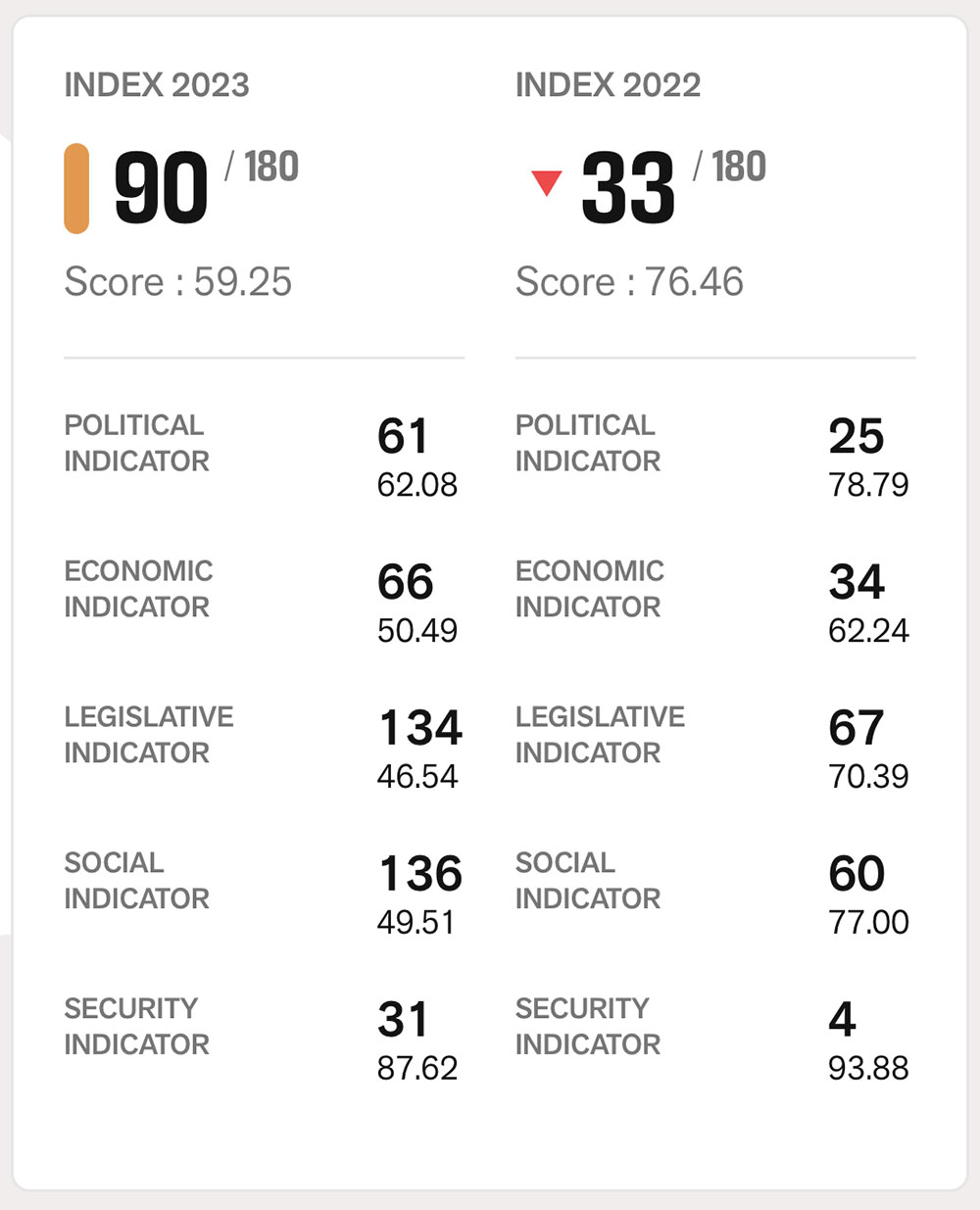

Bhutan’s press freedom ranking dropped to 90th place this year from 33, by 57 places, according to the 2023 World Press Freedom Index (WPFI) compiled by the France-based Reporters Without Borders (RSF).

However, even with the significant drop, Bhutan’s press freedom is much better in the Asian region. In the SAARC region, Nepal ranks 95, the Maldives 100, Sri Lanka 135, Pakistan 150, Afghanistan 152, India 161, and Bangladesh 163.

Norway ranked first with 95.18 points followed by Ireland and Denmark with 89.91 and 89.48 points, respectively. The index was declared yesterday by the RSF coinciding with the world press freedom day.

President of the Journalist Association of Bhutan (JAB), Rinzin Wangchuk, said the JAB is not shocked, but surprised by the ranking. “When there is no access to information, there will be no media freedom.”

He said access to information for Bhutanese journalists has never been as challenging as over the last few years. “The changing media landscape coupled with the high turnover of journalists is compounded by shrinking access to information, all of which is impacting news coverage and people’s access to information.”

“Even getting basic information has to go through several layers of bureaucratic procedures,” he said, adding that bureaucracy has been the biggest stumbling block for journalists in Bhutan.

State of Bhutanese media today

There are seven newspapers, and five FM radio stations in the country. The only television broadcasting station is BBS.

More than 80 journalists, including 20 from the print media, quit journalism in the past year. BBS alone lost 60 employees with news reporters, producers, camerapersons, and editors resigning from their jobs.

Low salaries, poor working environment, and difficulty in getting information are seen as factors influencing journalists to seek other careers or leave the profession for opportunities overseas.

In August 2022, JAB asked journalists to rate various government agencies based on access to information. Of the 30 respondents, 24 said that access to information was worse than in previous years. The survey found that the Prime Minister’s Office received the highest rating, while RCSC and Thimphu Municipal Office shared the worst.

Many media professionals agreed that the elected government is more open than bureaucrats when it comes to sharing information.

The bottleneck

Bhutan Civil Service Rules (BCSR), restricts civil servants from criticising or undermining government policies, programmes and actions in public or through the media. In July 2022, RCSC which is the central personnel agency of the government, introduced the Administrative Disciplinary Actions (RADA).

RADA is mainly to deal with civil servants who disclose critical information to an unauthorised person, audience, platform or forum and those who use official information for personal gains. “Strict enforcement of these new rules has further discouraged civil servants and officials from talking to the media even when they are only sharing necessary information to keep the public informed,” said Rinzin Wangchuk.

The Anti-Corruption Commission has also come up with a model code controlling public servants, which means they could face disciplinary action or criminal sanctions if they share official information, including non-confidential information, without authorisation.

In 2022, the National Assembly also issued a rule prohibiting the media from interviewing MPs during the session.

A senior journalist said that the rules are misinterpreted to stifle the media. “Nobody is willing to talk to the media even if they know it is important for public interest,” he said. “They ask us to write stories, but are afraid to share information.”

Way forward

Reporters said that government institutions and ministries have a responsibility to appoint media spokespersons and conduct regular press briefings, and also relax restrictions on official communications and set a timeline to share public information.

Reporters said the system of information dissemination needs to be made more efficient and transparent. “Public institutions must uphold the supreme law of the country, the Constitution, which explicitly states that power belongs to the people and not to the authorities.”

A reporter said that civil servants should be allowed to share information and even criticize government policies if they feel it is wrong without getting personal. “Quite often, the international media surprises the local media. It is a shame.”

RSF findings

RSF highlighted that Bhutan Infocomm and Media Authority (BICMA)’s officials are appointed by the government, and pose a threat to media independence. The report also mentioned that bureaucracy perpetuates a culture of secrecy and distrust of the press that ends up depriving the population of information of public interest.

“Recent defamation suits and a national security law penalising any attempt to create “misunderstanding or hostility between the government and people” have acted as a brake on journalistic freedom,” the report stated.

As per the report, 80 percent of advertisements in print newspapers originate from government agencies, and will have a direct editorial impact, which many editors agree.

Self-censorship among reporters is one of the problems cited by the RSF. It says that due to self-censorship, many reporters don’t cover sensitive issues.

Journalists in Bhutan rarely face physical threats, perhaps because they hardly uncover corruption or misuse of authority. However, the report states that investigative stories or opinion pieces of journalists may be subjected to online harassment owing to social media’s development in Bhutan.

RSF Secretary-General, Christophe Deloire, said the changes in the press index in most countries are a result of increased aggressiveness on the part of the authorities, growing animosity towards journalists on social media, the growth in the fake content industry, and the development of artificial intelligence.