Book Review

Author Dasho Dr. Karma Ura

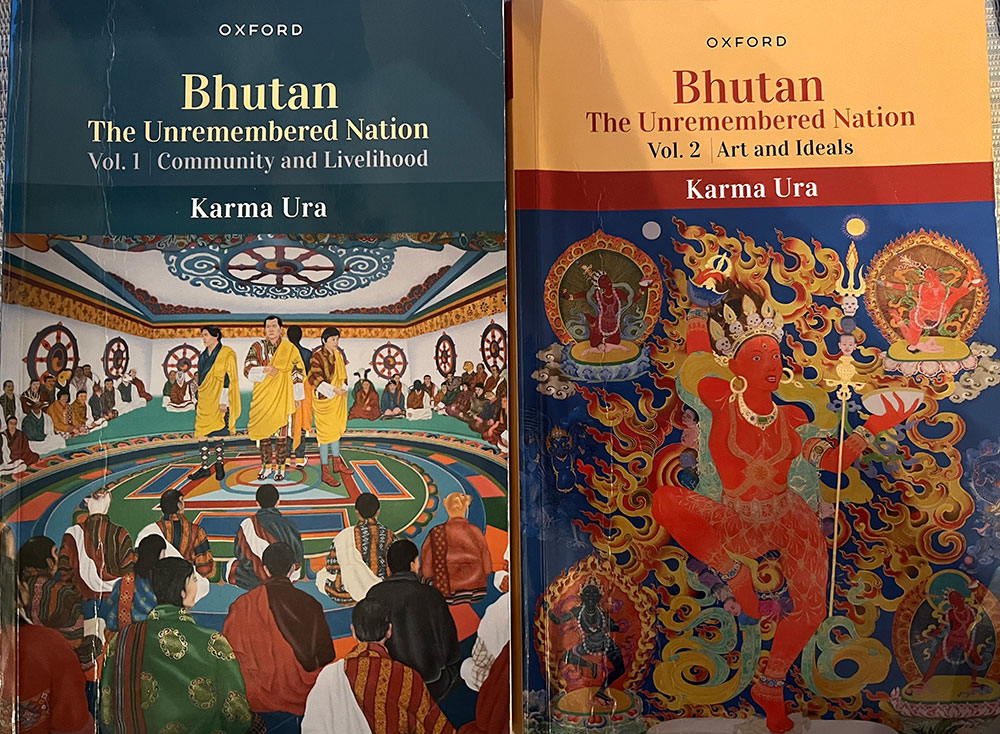

There is seldom a book, which breaks frontiers and emerges as profoundly monumental in a country’s history not only because of the scope and ambition of its subject matter, but also by the fact that it is the first to be published by one of its leading scholars with arguably the most prestigious global publisher. Dasho Dr. Karma Ura’s two-volume book aptly titled Bhutan: The Unremembered Nation is a book of daring ambition covering the whole gamut of the country’s cosmological, supernatural, demographic, legal, military, architectural, art, music ritual, linguistic, agriculture, trading, migratory and other traditions that are now rapidly being forgotten and ‘unremembered’.

Dasho Karma Ura, the first Bhutanese to study at the Oxford University and another equally prestigious British university, the University of Edinburgh, achieved a rare global distinction by publishing his seminal work with the Oxford University Press. A shorter version of the manuscript was submitted as a Ph.D. thesis to the Nagoya University’s Faculty of Graduate School of International Development in Japan.

Totalling 832 pages, the book was first conceived on the joyous occasion of the Royal Birth of His Royal Highness the Crown Prince Gyalsey Jigme Namgyel Wangchuck in 2016. The book has been dedicated to a Bhutan that will largely be forgotten and ‘unremembered’ by the time His Royal Highness assumes the destined throne of the Druk Gyalpo. The rapid developmental advances that the country has seen under the visionary Wangchuck Dynasty in fulfillment of the sacred prophecies of Guru Rinpoche, the country’s patron saint, and the prayers and dedication of Zhabdrung Rinpoche, its founder, has counterintuitively meant that a large part of the country’s social history has been lost to its posterity. Without the epic effort of a heroic scholar that is Dasho Karma Ura, the historical Bhutan will not only be ‘unremembered’ but may also become unappreciated and, worst, disparaged and undermined.

The book was first conceived as the country’s development history. But it has now shaped up as a defence of the many superior qualities of foresight, pragmatism, wisdom, resilience and versatility of its traditional livelihood and socio-economic strategies in opposition to the singular and Procrustean planning frameworks of modern development thinkers and practitioners whose worldviews and skillsets are limited by their narrow sectoral boundaries and inapt education received in distant lands. Noting the ingenuity and astuteness of the country’s historical economy, the author writes:

“The discourse that was needed to justify the change in the farming system encouraged a perception of the country in negative terms: as small, rugged, mountainous, remote and unsustainable for farming… The image of being small, marginal, and rugged was meant to apply equally to its farms, which tended to become a self-fulfilling prophecy, contrary to the historical view of it as a fecund land” (Vol 1, p. 282).

Dissecting the present decline in agricultural productivity compared to the historically flourishing pastoral and farming culture, two chapters demonstrate how the shift in breeds and varieties over the last 60 years has had unexpected and unsatisfactory results.

The book is also a masterful triangulation of statistical and administrative data with social science analytical frameworks in the hands of a career civil servant who has achieved well deserved global repute as a rigorous multi-disciplinary scholar. The author draws on all quantitative data of the country from the mid-eighteenth-century record on taxable households to the first crude GDP estimate done in 1985 from whereon quantitative socio-economic baseline data on the country started to be regularly published.

Taking a sharp view of the bureaucracy’s propensity to overregulate, the author constantly bemoans the lost opportunity to retain a vibrant rural livelihood through the bureaucracy’s indiscriminate adoption of supposedly modern and improved conservation and economic practices. The interrelated loss of agricultural lands due to a plenitude of unmanageable land use regulations in the name of advance sustainable policies, and the resulting loss of farming and pastoral productivity, have led to the creation of an unsustainable and unliveable rural landscape. It has also led to the tragic loss of people’s intimate connection with the land as well as their deeply symbiotic relation resulting in not only loss of the people’s deep reverence for the ecology, but also loss of their intergenerational knowledge of the lands that they inhabited.

The culprit of the loss of our rural livelihood and other intangible heritage is not only the bureaucrats, who are never in a position long enough to be accountable for the consequences of their actions, but religious individuals of various kinds are equally liable for undermining localised animist ritual practices that are actually more conducive to living sustainably on the land.

So, what has actually been lost and is now largely ‘unremembered’? The Bhutan that has now been assigned to the recesses of the frail and failing memories of a disappearing generation of people born before the 1960s when seismic and structural changes were first introduced in the country is the diverse subject of the two-volume publication. The first volume titled Community and Livelihood contains seven chapters of varied lengths including an introductory chapter that is shared in both volumes. The second volume titled Art and Ideals similarly contains nine chapters including the shared introduction. The book fits into the mode of ‘sensuous scholarship’ as propounded by the renowned anthropologist Paul Stoller, and draws on all bodily faculties and senses in providing lucid descriptions of the smells, tastes, sounds, textures and other sensations of the country.

The two volumes display amazing depth and breadth of the eclectic scholarship of a great Bhutanese polymath hearkening the best tradition of gentleman scholarship of the foregone days while matching the sensuousness of this narrative genre with the rigours of modern scholarship. These dual qualities make the book not only an encyclopaedic and authoritative reference for scholars on Bhutan particularly, and the development history of the Himalayas and South Asia generally, but also a book that can be read and enjoyed by any savant person.

To borrow a Marxian phrase, Volume 1 forms the description and analysis of the infrastructure of Bhutanese material culture. Chapter 2 opens with the construction of the rammed-earth ‘mother house’ (ma khyim) and proceeds to other chapters of ‘family and village’ (chapter 3), ‘perfect cows and skilled herdsmen’ (chapter 4), ‘sounds and colours of the land’ (chapter 5), ‘back-pack traders and caravans’ (chapter 6), and ‘rhythms of farm life’ (chapter 7).

Volume 2 contains the materials on the superstructure of the Bhutanese high culture and opens with Chapter 2 on the ubiquitous feature of Bhutanese landscape, the majestic Dzongs titled ‘castles of eternity’. It is followed by ‘visual arts and visualisation’ (chapter 3), ‘tapestry of beliefs and faith’ (chapter 4), ‘governance of the nation’ (chapter 5), ‘apex of power’ (chapter 6), ‘troops of fierce deities’ (chapter 7), ‘monks and monasteries’ (chapter 8) and ‘the timeless Guru’ (chapter 9).

These interrelated chapters incrementally lead towards the argument that the traditional Bhutanese worldview and consciousness is not only shaped by its built environment, and tapestry of Buddhist and animist spiritual cultures, but also by the sight and sounds of the landscape’s caressing wind and/or cascading river (kyiser lungma and changchang chum). The people born and raised under such a wholesome surrounding not only develop an innate bond with it, but also an intimate knowledge and respect for it with an ethics of love and care.

Another feature that the author’s sensuous prose brings out is the country’s pragmatism and material frugality in the past that was matched and sublimated by an uncommon broadness of their worldview and perspective. Persevering as a sovereign country amidst tumultuous geopolitical tensions needed the country to be self-reliant. The chapter titled ‘apex of power’ describes proscription on official extravagance, and describes the regulatory requirements of state officials of all level who lived and worked within the Dzong’s perimeter to share meals in a common mess. This not only promoted a commensality unseen in other medieval socio-political structures, but also saved precious resources that freed people from the burden of overwhelming taxations.

The ethics of frugality also expanded to encompass the people’s personal lives, and they were customarily not only required to limit excesses especially in times of birth and death, but also social occasions like marriage, and other celebratory and commemorative occasions. This explains why there is no extravagant and burdensome wedding culture in Bhutanese societies where state laws and customs were diffused, but also why Bhutanese generally adopted a frugal and pragmatic worldview that enabled them to dynamically and resiliently manoeuvre inevitable turmoils without the burdens of prohibitive habits and traditions.

What Bhutanese compromised on material extravagance was made up with the uncommon vastness of their thoughts and perceptions. The ubiquitousness of phallic images and exhibitionist tendencies in nude ritual dances called ter-cham is a case in point. The author argues that such “displays were dedicated to fecundity and vitality of men and animal…, and representations of sexuality, full nudity in certain performances, without any unease of the prudish, were a norm in the past” (Vol. 2, p. 78). He bemoans what he calls an ‘attitudinal change’ occurring in the country towards a “decline in public humour, complexity, and profundity, and an escalation in private facetiousness, plainness and triteness”, together with unwelcome and unhealthy “repressive tendencies”.

Dasho Karma Ura transcribes and translates an impressive repertoire of representative oral poems, songs and liturgies, which vividly carries a rural, but sophisticated oral, culture that artistically and candidly conveyed a diversity of human emotions, including those that are repressed in today’s hypersexualised world. The author also provides one of the most authoritative disquisitions of Bhutan’s phonetic and lexical richness as a result of its many languages including a comparison of the contrasting sounds of the two major languages, Dzongkha and Tshangla.

Dasho Karma Ura’s book also intimately provides rare insights and analysis of the monarchy and its household affairs. The author highlights the selflessness and responsiveness of the revered Wangchuck Dynasty. Responding to people’s welfare concern, successive generations of the Dynasty introduced progressive and dynamic reforms, which eased age-old burden on the people including overbearing tax obligations, and allowed them to experience unprecedented reprieve and prosperity. Reform initiatives invariably began with the royal households. For example, a selfless reform that had a great effect in expanding pastoralist culture was the ceasing of the practice of keeping royal herds that freed a great deal of pastureland for ordinary pastoralists.

Indigenous textual sources in Bhutan are often written by monk-scholars who had little interest or aptitude to describe secular matters in their works. Despite the scarcity of historical socio-economic source materials, Dasho Karma Ura’s comprehensive command of Choekey has allowed him to refer exhaustively to all available national and religious histories, hagiographical writings, collected works of religious masters, recorded local histories and ritual texts, etc. A significant source of the author’s historical information comes from his equally extensive use of foreign, mostly British colonial, records.

Making virtue out of necessity, he has relied heavily on oral interviews with knowledgeable elders over a career that has spanned decades. Most of the data is based on interviews and observations from the field that were conducted both by the author and his research assistants. The author has diligently and sincerely acknowledged all assistance that he has received at various points in his book. Needless to say, such a virtue is uncommon in native Himalayan scholarship where claim of individual authorship in arts, literature and scholarship are often inadequately acknowledged.

The book diverges from normal ethnography in that data were collected from representative sample areas all across the country, sometimes with the help of assistants. This makes the scope of the book very ambitious, but the author’s objectivity in analysing his data reflects in the fact that he has been able to transcend innate bias towards his own root and region, that often plagues indigenous scholars, and properly integrate materials from all regions of the country in the writing of an objective history of national development. The bulk of the data is drawn from Western Bhutanese areas which was materially the most advance region, and contains extensive verifiable historical materials. On the other hand, due to standardisation of religion and culture in this region, the folk cultures including wedding customs show more variety in Eastern Bhutan where they escaped the state’s diffused standardisation efforts. As the spiritual heartland of the country, central Bhutan demonstrates a profound diffusion of Buddhist traditions.

For a book with such ambitions dealing with a vast array of disparate thematic areas, sometimes the depth of materials and analysis are variable. For example, the chapter on Dzongs is only 13-pages long while the subsequent chapter on art is 73-pages long proving that such an ambition can sometimes become untenable even for an erudite scholar like Dasho Karma Ura. But as commented by Geoffrey Samuel, another scholar who wrote an even more ambitious textbook on the ethno-history of the entire Tibetan cultural area, “this book is an essential reading for anyone who wishes an in-depth understanding on this Buddhist kingdom in the Himalayas”.

Most importantly, the book captures all the sounds and sights, rich tapestry of faith and healing, nature and nurture, governance and institutions, which went into safeguarding the country through four centuries of uninterrupted sovereignty. As the author argues, “when we look back across four hundred years since Zhabdrung began building the larger state of Bhutan, a sobering picture emerges. Almost all the states which existed at the time of Zbabdrung and with whom Zhabdrung interacted in the neighbourhood such as Kingdoms of Darrang, Koch Hajo and Koch Bihar, Ahom, Sikkim and the Tibetan theocracy have not survived. His blessings have enabled all virtuous rulers and institutions of Bhutan to keep the people and nation flourishing as an exception in the march of Himalayan history” (vol. 2, p. 157). Even as the trajectory of national progress continues unabetted as our nation moves through another paradigmatic shift under the farsighted leadership of His Majesty the King, Dasho Karma Ura’s magnum opus ensures that our undying national spirit of resilience and dynamism is recorded for posterity, and will continue to shine a light on our way forward as a proud nation state.

Reviewed by: Dendup Chophel, Research Fellow, Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg, Germany