Choki Wangmo | Tsirang

Local chicken breeds are not only highly adapted to the natural environment but are also an integral part of the lifestyle of rural people. With the introduction of exotic breeds in the country, backyard farms disappeared gradually.

Two kilometres along the Mendrelgang-Barshong gewog centre road in Tsirang, 13 households of Dzamlingzor Chiwog in Mendrelgang are reviving the indigenous practice.

Dzamlingzor Yubja Detshen is one of the three groups in the country rearing native chicken breeds on a commercial scale.

The group has come a long way to establish itself in the market. The group’s chairperson, Suk Man Layo Monger, believes that the way forward would be less challenging.

During his school days, Suk Man’s parents received poultry equipment and four layers with the support of the livestock sector. However, the equipment lay idle. After a week’s training, Suk Man formed the group in 2015.

With the help of the National Biodiversity Centre, each household received 6,600 pullets. Each household contributed Nu 6,000, from which Nu 5,000 was used to buy pullets and Nu 1,000 as seed money for the group.

The group sold 1,500 pullets to farmers in Gasa, Dagana, and Damphu Town so far.

“The chickens are hardy and provide a valuable protein source to rural households. The succulent meat is in high demand,” he said.

The group has a sales outlet in Motithang, Thimphu.

A kilogram of indigenous chicken costs Nu 400.

The group has not faced any marketing issues.

Farmers said that the low-input indigenous chickens (Gallus domesticus) adapt to harsh environmental conditions and are resistant to disease as they feed on organic feeds like maize, grains, and boiled nettles.

In a day, 600 layers feed on 30 kg of maize.

“During the feed crisis a few months ago, we did not face such problems,” one said. The issue with organically raised chickens is low productivity. He said that the productivity increased with imported feeds but the quality of eggs and the chicken was low. “But we want to focus on the indigenous breed preservation,” he added.

The first hatch from the indigenous breed is of low quality and improves as the production progresses.

An egg costs Nu 12.

The farm has five breeds of chickens—Kaap or white Belochem, Pulom or Frizle, Naam or Pure Black, Khuilay or Naked Neck, and Crested Belochem.

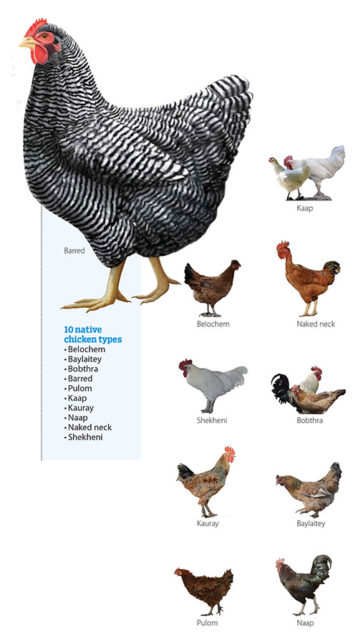

The records with the Department of Livestock show that the native chicken population constitutes about 12 percent of chicken population. Bhutanese native chicken is classified into 10 types, comprehensively described based on plumage, feather, and body size.

The production is impeded by wild predators.

The group has proposed for a wire mesh to the dzongkhag administration. The members also do not have enough housing for chickens. As the chiwog doesn’t have a farm road connection yet, transportation cost is high too.

There is high demand for day old chicks (DoC). “We produced 600 pieces of DOC but the 602-capacity poultry machine has been defunct for two months now,” Suk Man said.

Without equipment, it takes 21 days for a hen to hatch the DOCs, which can be done twice by the machine within the same time period.

Hens damage the eggs and there are risks of infection, he said.

Local chickens can lay 20 to 80 eggs per year, which is very low compared with commercial breeds that can lay up to 300 eggs per year. Nutritional deficiency and low genetic potential are some of the factors influencing the low production of eggs.

About 66 percent of rural households in Bhutan rear chickens on backyard farms. Backyard chicken farming in the country is characterised by rearing native chicken under minimal management input mainly under scavenging and free-ranging conditions.

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization, 33 percent of local chicken breeds are facing extinction.

Tsirang has 300 exotic breed and broiler farms.