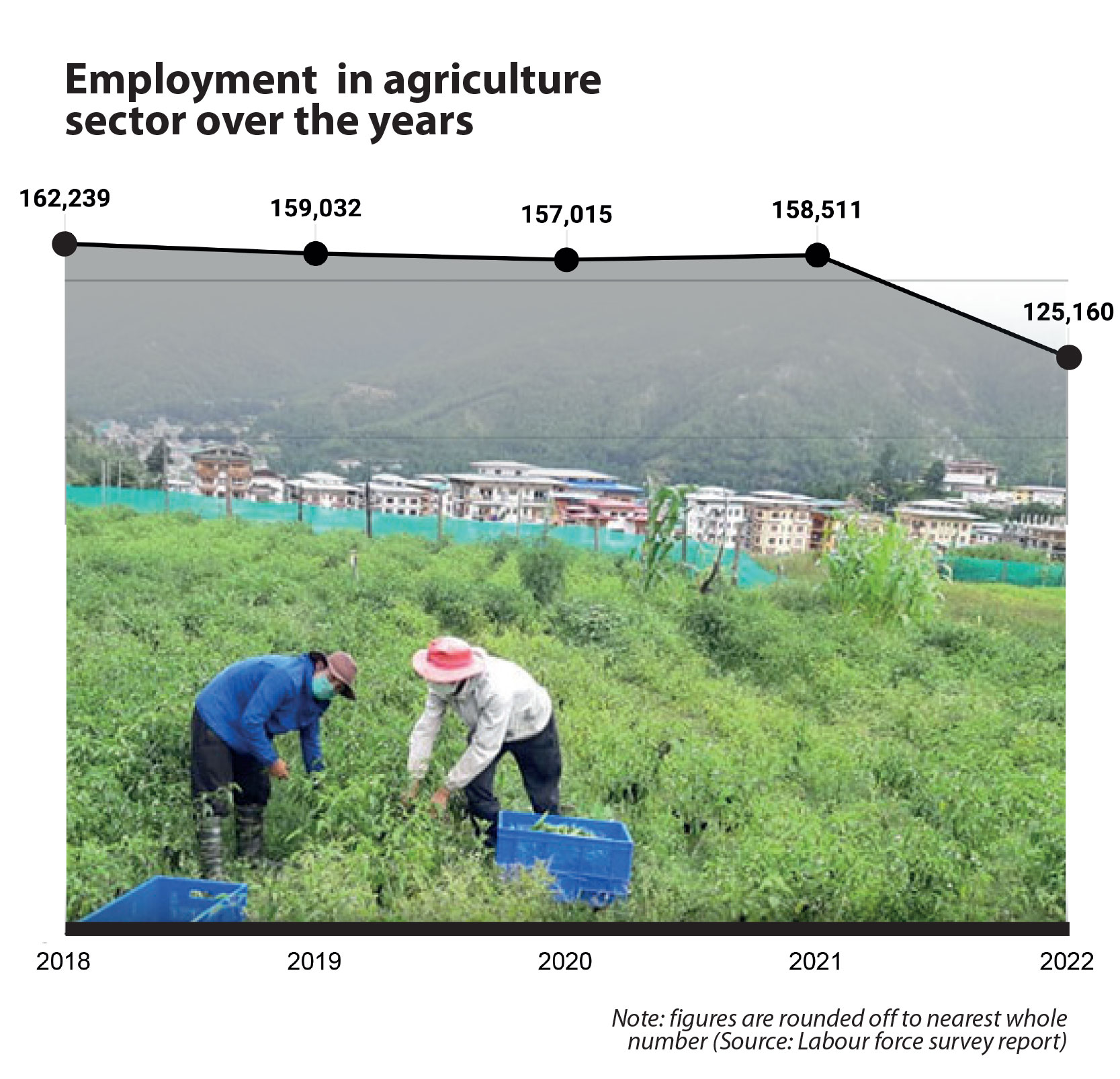

… employment in agriculture decreased by 22 percent in the last five years

Yangyel Lhaden

Nima, the last man to practice agriculture in Namkha aring, once an agro-pastoral community in Mongar gave up on cultivating rice on his one-acre land this year.

Acute water shortage and human-wildlife conflicts have forced the farmers to abandon agricultureal land in Namkha aring and neighbouring communities.

“I continued cultivating on our ancestral land even when everyone else gave up,” Nima said. This year, it was impossible for the family to cultivate as the water source has dried up and the monsoon was untimely.

Nima currently supports his family by working on farms in other villages.

He said that it was disheartening when a year’s hard work was damaged in a single day by wildlife. “Wild boars, porcupine, and monkeys are common pests in Namkha aring. I can never earn enough for a living by working on my farm.”

Although agriculture engages most Bhutanese, the data from Labour Force Survey Reports (LFSR) over the years show an increasing trend of people abandoning agriculture.

In 2018, 162,239 individuals, 54 percent of total employed were engaged in agriculture, but last year the number reduced to 125,160, 43.5 percent of total employed persons, according to LFSR 2018 and 2022.

This means there will be about 22 percent fewer employed individuals in agriculture in 2022 than in 2018.

Post pandemic, agriculture employment has drastically reduced, with only 66,075 women and 59,136 men employed in the sector last year.

Doten Lhaden from Yurung, Pemagatshel, has abandoned rice cultivation for about two decades. “When water was abundant, the yield was good but over the years as population increased, there was an acute water shortage. I had to abandon farming.”

Yurung Gup Sangay Thinley said that increasing human-wild life conflict and rural-urban migration has led people in his gewog to leave agriculture.

“It is easier for villagers to earn by doing daily wage work rather than working on a farm,” Sangay Thinley said. “The fallow land from gungtongs is also attracting more human-wildlife conflicts, affecting other farmers.”

Of the 402 households in Yurung, 114 are gungtongs.

He said that increasing numbers of women in Yurung were earning from weaving while men were engaged in daily wage work.

An old Rai couple in Zomlingthang in Sarpang who grows millet says that their land would be left fallow once they grow old as their children are not interested in agriculture. Every night, the husband guards the produce from elephants. “Our yield has been reducing every year and there is nothing much we can do with elephants destroying our field.”

As farmers abandon farms, the country’s fallow land has increased, with a total fallow land of 66,120.32 acres in 2019. Bhutan has a total arable land of just seven percent—664,000 acres—but only two percent is under cultivation.

A pilot study conducted to implement fallow land bank initiative by the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock and National Land Commission Secretariat last year, found that some of the major causes of fallow land were labour shortage, lack of water or irrigation facilities, human-wildlife conflict, and distance of the land plots from human settlement.

Women in agriculture

There has been a noticeable decrease in women’s representation among skilled agricultural and forestry workers, with figures dropping from around 89,000 in 2020 to 65,700 in 2022.

Based on the data from LFSR 2018, 2020, and 2022, there has been a noticeable increase in the number of regular women employees in rural areas. The figures rose from 7,000 in 2018 to about 9,300 in 2020 and further to more than 9,600 in 2022.

Agriculture and GDP

The sector’s contribution to the country’s economy is the least. In 2021, the sector only contributed around 19.2 percent or about one-fifth of the country’s gross domestic product amounting to Nu 36.04 billion, according to the Royal Monetary Authority’s annual report.

Although agriculture’s share in GDP increased in 2021 from 14 percent in 2015 to 19.2 percent in 2021 but agriculture sector’s per income earning relative is nine percent lower at Nu 227,346 from GDP per capita of Nu 248,334.

Meanwhile, the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock is leading the effort to tackle challenges by adopting climate-smart agriculture techniques. They are focusing on using real-time climate data to assess technologies such as weather services and improving crop production. To manage water resources effectively, measures like rainwater harvesting, drip irrigation, and piped channels are being employed. Additionally, climate-resilient crops like heat-tolerant maize and citrus varieties are introduced to enhance the sector’s adaptability to changing climates.