The article by Dr Phuntsho Namgyel critiques Bhutan’s forest laws which is supposedly influenced heavily by colonial policies and mindsets; restricting forest resources to the people and criminalising people who use forest resources without “permits’’ while inferring to it as “anti-people” (Bhutan Forest Act (BFA) 1969), “anti-development” (Forest and Nature Conservation Act (FNCA) 1995) and altogether inferring to the FNCA 2023 as both “anti-people” and “anti-development”. The article also refers to an increasing forest cover and decreasing contribution of the forestry sector to Bhutan’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) while advocating for policies that support sustainable development, biodiversity conservation, and poverty alleviation, emphasizing the need to adopt a decolonized mindset for better forest management and economic growth.

Since the article is mostly based on inferences and imaginative power, the Department of Forests and Park Services (DoFPS) would like to clarify the following points.

Wildlife crime on the rise

The DoFPS acknowledges the increasing interception of wildlife offences, which is mostly attributed to the increasing efforts of the forest rangers and interventions put in place by the Royal Government of Bhutan (RGoB) to combat wildlife crime and trade. However, the article segregates and indicates “wildlife” as only meaning wild animals, which is not correct. The FNCA 2023, refers to “wildlife” as both wild flora and fauna, generally referred to as plants and animals respectively. Therefore, “forest offence” and “wildlife crime” are used as synonyms in the Bhutanese context and refer to any illegal acts committed in relation to wild flora and fauna.

Is peaceful Bhutan a hotbed for international wildlife crime?

Global trend in wildlife crime: Dr Phuntsho Namgyel’s article infer to the Kuensel Articles on wildlife crime dated July 20th 2024 which also cites the World Wildlife Crime Report 2024 published by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). Dr Phuntsho Namgyel incorrectly interprets “wildlife crime” as only involving “animals”. The UNODC report provides a comprehensive analysis of global wildlife trafficking trends and highlights the involvement of transnational organised crime in wildlife trafficking across 162 countries. For Bhutan, while the country is not highlighted as a major hub for international wildlife crime, it being part of the broader global network affected by wildlife trafficking and the possibility of Bhutan being used as a transit route cannot be ruled out.

Forest legislation in

Bhutan: The assertion that Bhutan’s first forest law, the BFA 1969, “influenced by British colonialism and imported from India”, nationalized all forests extinguishing customary rights is inaccurate. While the BFA 1969 did nationalise forests, it did not eliminate customary and traditional rights. Additionally, the FNCA 1995 introduced community forestry programs, encouraging people’s participation in forest management. Further, Protected Areas (PA) which existed in Bhutan since the 1960s, were officially notified in 1993 and gazetted in 1995, with the Wangchuck Centennial National Park added in 2008. To enhance ecological connectivity, Biological Corridors (BCs) were established in 1999, with the latest addition of BC 9 in 2023. The current PA Network integrates global conservation principles tailored to Bhutan’s unique socio-cultural context, following the Four Pillars of Gross National Happiness (GNH). Thus, people and nature coexist harmoniously through integrated conservation and development programs, where customary and traditional rights are protected and communities constitute important partners of the mainstream development process.

How Permit Raj, rationing and sanctions push farmers towards

criminalisation?

Right to access and use of forest resources: Forest was nationalised through BFA 1969 to curb increasing pressure on forest because of the open and easy access to forest resources, which emphasised the importance of scientific management of forest for economic development of the country and to meet the societal needs in perpetuity. Contrary to claims in the article, rural communities continue to enjoy access to forest resources. Non-wood forest products (NWFP) can be obtained free of royalties for self-consumption, and the communities that reside near or rely on certain NWFPs are given priority for access for commercialization of these resources. Various social forestry initiatives have helped communities across Bhutan build their livelihoods through the sustainable harvest and sale of forest resources with cordyceps in the North, cane & bamboo in the East, matsutake in the West, to name a few.

Further, people residing in rural areas are provided with subsidized timber for new house construction, renovation as well as for other forms of construction. The quantity, periodicity and frequency of allotment were to facilitate the construction of a decent rural house to live in, embracing the standard traditional structure and design of the typical Bhutanese house. Considering the durability and long rotation period of the timber (ca. 80 to 120 years) and the longer economic life of timber, it is only reasonable to allot timber once every 25 years. For example, structural timbers in most rural houses, Lhakhang, and monasteries are older than 25 years. However, this system does not restrict anyone from applying for additional timber at commercial royalty, if required.

Public services: In terms of service delivery, the RGoB has always placed a greater emphasis on public service delivery. Thus, the forestry service has evolved from a lengthy manual process to an end-to-end online system. The Online Forestry Services (OFS) and the Government to Citizen (G2C) system provide a digital platform to avail most of the forestry services online. The current permit system helps to authenticate the source of origin of a resource to account for the economic contribution from private and SRF land.

A review of forest offences shows that many detected cases involve the illegal extraction of timber for sale rather than the domestic needs. The article asks the DoFPS to move away from the colonial mindset and the perceived “permit raj system” in existence. While the reign of the Permit Raj system was characterised by providing preference to large corporations, being prone to corruption and increasing the wealth inequality, the reforms to forestry in Bhutan was adopted to ensure equity and equality amongst citizens in a transparent and fair manner.

Basis for forest rules: Bureaucratic power, not science or environmental concerns

Science behind forest policies and laws: The Thrimzhung Chenmo, 1957 provided open access to forest resources, with restrictions only on hunting and poaching. This led to increased pressure on forests. Therefore, recognizing the need for “protection, conservation and scientific management of forests” for the national economy, the BFA 1969 was passed. The BFA consolidated all laws related to forest, the trade of forest produces and duties levied on timber and other forest produce. The BFA and the subsequent National Forest Policy (NFP) 1974 were enacted with the well-being of the Bhutanese people and “above cardinal principles of vital national interest” in mind, contrasting with the objectives of the colonial administration highlighted in the article. The FNCA 1995 emphasised the social forestry program, thereby promoting people’s participation in forest management.

Forest management in Bhutan is guided by the Forest and Nature Conservation Code of Best Management Practices (the Code), which compiles best practices from around the world and scientific research conducted through, the DoFPS, the then Renewable Natural Resources Research and Development Centre (RNRRDC) under the guidance of the Council for RNR Research of Bhutan (CoRRB) and the Ministry, the Ugyen Wangchuck Institute of Forestry Research and Training (UWIFoRT), as well as relevant projects and agencies focused on forestry and environmental research. Bhutan’s legislation has considered emerging issues in forest management over the years and has adopted scientific studies and approaches with an emphasis on sustainable forest management.

People’s participation in forest management and legal framework: Local communities are important partners and stewards in forest management in Bhutan. They are consulted, and their voices heard while formulating and enacting forest laws, rules, and regulations. Communities have been engaged in social forestry programs since 1985, and the concept of community forestry is provisioned in FNCA 1995 and FNCA 2023. The FNCA 1995 specially emphasized on social forestry and encouraged the participation of community and private individuals besides outlining the requirements of a management plan for the production and protection of forest and wildlife including the PA system in Bhutan.

Forest conservation and protected areas in Bhutan: Bhutan’s conservation strategy differs significantly from “wilderness ideology from the west” highlighted in the article. In Bhutan, PA is designed to support both people and wildlife, allowing local communities to coexist unlike the Western system wherein all local communities residing within the PA network are displaced. While there are some restrictions within these PAs, they are not inherently anti-development. The FNCA 2023 respects the national circumstances and customary rights are protected, it also provides provision of developmental activities for the local communities and national interest in the PA. This is far from the concept of the PA system practiced in the West. Rather, Sustainable Forest Management (SFM) in Bhutan is based on scientific principles and environmental concerns to ensure the sustainability of forest resources for the current and future generations. The need for forest protection stems from Bhutan’s geo-physical conditions, with steep slopes and mountainous terrain prone to devastating downstream flooding, soil erosion, and reduced agricultural productivity.

The state of forest cover today

Forest cover reporting consistency: The forest cover reported by the DoFPS and other agencies, such as the National Soil Service Centre (NSSC) (2010) and National Land Commission (NLCS) (2020), have used comparable definitions which is consistent with definition in the NFP 2011 and FNCA 2023 wherein forest is defined as “land with trees spanning more than 0.5 hectares, with trees higher than 5 meters and a canopy cover of more than 10 percent” and excludes land predominantly under agricultural or urban use. Bhutan’s forest definition aligns with the globally accepted definition adopted by the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO) and the UN Convention of Biological Diversity (UN-CBD).

Exclusion of shrubs and meadows: Shrubs are not considered a part of the forest because they are phenotypically different from trees. The Land Use and Land Cover of Bhutan (LULC) 2016 defines shrubs as “perennial plants with persistent and woody stems without any defined main stem, with height less than 5 meters”. Many countries, such as Australia, Austria, Finland, Germany, India, and Nepal, also do not define shrubs as forests. Therefore, reporting an increase in shrub cover with no substantial increase in forest cover may be accurate to some extent, except for the LULC 2020. However, the statement that “shrubs in Bhutan contain 58 million m³ of timber” could not be verified since shrubs contain woody mass that can be used for various purposes but not as timber.

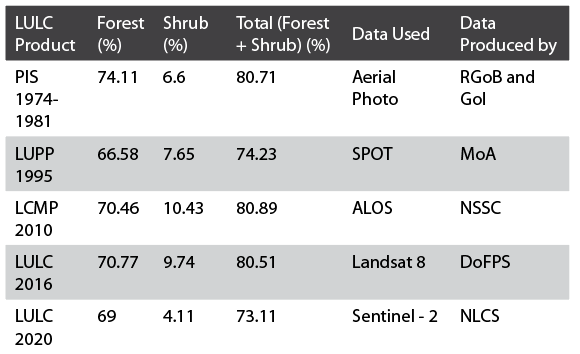

Comparison of the five land cover assessment; Pre-investment Survey of Forest Resources (PIS) (1974-1981), Land Use Planning Project (LUPP) 1995, Land Cover Mapping Project (LCMP) 2010, Land Use and Land Cover of Bhutan (LULC) 2016 and LULC of Bhutan 2020 carried out by different agencies in Bhutan shows decline in forest cover from 1981 to 1995 (7.53 %), increase from 1995 to 2010 (3.88 %), marginal increase from 2010 to 2016 (0.31 %) and subsequent decline from 2016 to 2020 (1.77 %). The table below provides the estimates for forests and shrubs in the different assessment.

The real crisis in Bhutan’s forests

Growing stock estimates: The growing stock of forests in 2015 was 944 million m³, not 1,001 million m³. This forest estimate does not include 57 million m³ which comes from trees on non-forest land, such as solitary trees within thromdes, orchards, fodder trees, trees on grassland, etc. The most recent estimate from the National Forest Inventory (NFI) 2023 indicates a growing stock of 759 million m³. This reflects a net decrease in growing stock since 2015, primarily due to a reduction in forest area and decreased stocking density. While it is reasonable to note an increase in growing stock from 1981 to 2022 by 5.6 million m³ annually, there has been a decline of 26 million m³ per year from 2015 to 2022.

Challenges in sustainable forest management: The Forest Resources Potential Assessment of Bhutan (FRPA) 2013 estimated that 1,071,830 hectares of total forest area are suitable for production management, accounting for 39.45% of the total forest area. Thus, forest management and utilization in Bhutan face challenges due to difficult terrain, steep slopes, poor accessibility, rendering forest operations economically, ecologically, socially, and technologically unsustainable. Furthermore, forests near existing roads and settlements have been overharvested, and any efforts to sustainably increase timber production will require investment in more remote areas.

While the DoFPS is striving towards bringing all forest under management as recommended by the NFP 2011, given the local geographical features and conditions, there are major areas with slopes exceeding 100%, which are unsuitable for production management and are often classified as inoperable forest areas. These regions have thin soil layers and steep terrain, making them prone to erosion if tree cover is altered or removed, leading to significant environmental and ecological consequences.

Bhutan is a net importer of wood and wood products: Bhutan Trade Statistics (2023) indicate that Bhutan imports wood, and wood products. However, a closer analysis of the statistics reveals that imports are primarily composed of semi-finished and finished wood products, with charcoal being the most imported item, followed by plywood, veneer, and particle board. This indicates that Bhutan mainly imports value-added wood products rather than raw timber.

Moreover, records maintained by the DoFPS indicate that the issues are related to extraction and disposal rather than timber supply. Over the last five years (2019-2023), the DoFPS allocated 26.53 million cubic feet to the Natural Resource Development Corporation Limited (NRDCL), but they have only extracted 19.91 million cubic feet. Furthermore, NRDCL is currently facing significant challenges in timber disposal. For instance, timber harvesting in the Metapchhu Forest Management Unit (FMU) in Chhukha, Rongmanchu FMU in Lhuentse, Khenzore FMU in Pemagatshel, and Dongdechhu FMU in Trashi Yangtse has been halted due to difficulties in timber disposal. Similarly, there are challenges in the disposal of timber extracted from scientific thinning areas.

Trends in forestry sector contribution to GDP: The percentage contribution of “forestry & logging” to GDP is on the decline, even as its absolute contribution continues to rise. This only shows that other, secondary and tertiary sectors are also growing in Bhutan, albeit at a more rapid pace to the forestry sector. Further, the current GDP accounting methods primarily consider, through livelihood studies, the value of non-commercial firewood, along with commercialized timber through the NRDCL, and cordyceps figures, largely overlooking almost all other non-wood forest products and the intrinsic value of ecosystem services provided by forests, not to mention the value of non-commercial subsidized timber from areas outside FMUs. For example, revenue generated from hydropower is attributed solely to the hydropower sector, neglecting the forest’s crucial role in reducing upstream sedimentation, which could otherwise lead to significant maintenance costs.

Investment in forest management: The DoFPS recognizes the high density of smaller trees contributing to dense forests, which can negatively impact biodiversity conservation and increase the risks of wildfires, pests, and diseases. This has also been reflected in the State of Forest Report 2023 wherein more than 70 % of the trees were found in smaller diameter class (diameter at breast height (DBH) less than 40 cm) and has recommended scientific thinning to be carried out in such stands. Similarly, annual scientific thinning is carried out in SRF land including forest areas managed under different regimes such as FMU, Local Forest Management Areas (LFMA), Community Forest (CF), and PA Networks, all guided by approved management plans. In areas outside these managed areas, thinning is conducted based on thinning guidelines and technical prescription of the Code.

Further, the DoFPS initiated a nationwide scientific thinning program in September 2023; the first phase (October to December 2023) followed by the Phase II started this year. This initiative with an annual allowable cut (AAC) of 699,141 m3 in standing volume aims to bring more forests under planned management through approved forest management plans, and the harvested timber from the nation-wide scientific thinning program will be exported.

Conclusion: The RGoB under the visionary leadership of our Monarchs, has over the years, worked tirelessly towards fulfilling the needs of the people on forests, while simultaneously keeping in mind the immense importance of the conservation of the environment to fulfill Bhutan’s national and international commitment. The DoFPS acknowledges the contributions of veteran foresters who have shaped our forest management practices and the ongoing efforts of current foresters to carry on this legacy and serve the nation. We also extend our special thanks to Dr. Phuntsho Namgyel for his guidance in forest management during his tenure at the Department of Forests and Park Services and beyond. He contributed significantly to drafting numerous policies and guidelines. His regular, thought-provoking, and constructive criticism on forest management has always helped us refine our approach. Articles like this highlight the need for DoFPS to provide more clarity and insights into Bhutan’s forest management, a pride for Bhutanese and global admiration.

Contributed by

Department of Forests and Park Services

Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources

(fmid@moenr.gov.bt)