Demographics of migration

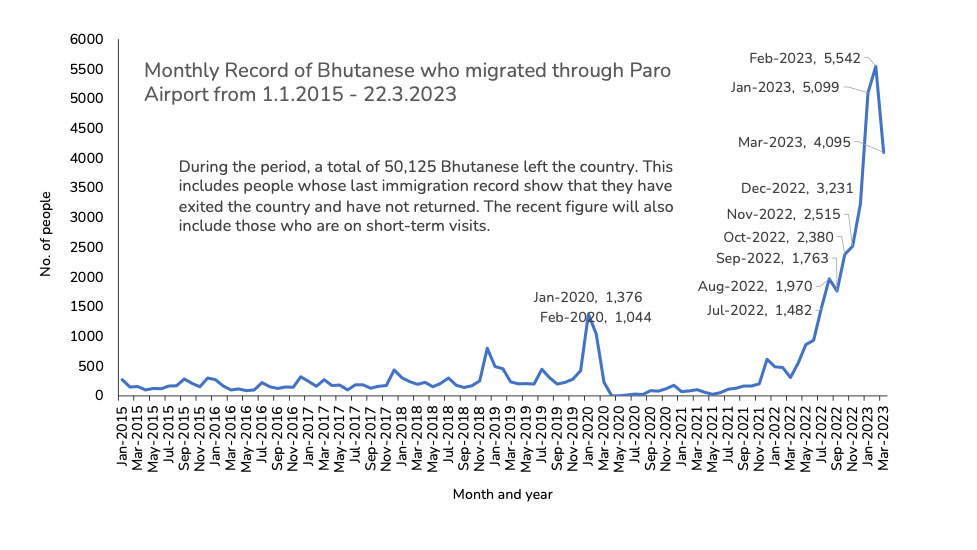

10,240 babies were born and 5,115 persons died in 2020. The net increase in the population per year is about 5,000 though this number is going down due to decline in births. If yearly migration is 5,000 per year, the yearly net increase in population is completely offset. The number of migrants that is recorded is not 5,000 per year, but 5,000 per month for the early part of 2023. From Paro Airport alone, 16,973 migrated in 2022. This number is equivalent to the population size of Bumthang district. This migrant number excludes those who left through other land exits. Australia is by far the most frequent destination. Between January 1, 2018 and March 22, 2023, 13,583 Bhutanese left for Australia, through Paro Airport. The monthly numbers have surged continually. It is a turn of events no one anticipated before or during the covid period during which His Revered Majesty’s phenomenally brilliant leadership of compassionate relief and protection of human life was demonstrated.

Thanks to Immigration Department, the most usable data, although not the best possible, on migration could be extracted from the exit and entry records maintained at Paro International Airport. The latest data used for estimation of migration in this article ends on March 22, 2023. Paro Airport entry and exit record starts from January 1, 2015. Using either CID or passport numbers, duplications and multiple entries were ruled out and those who exited and did not return were considered migrated. A tiny fraction of those who exited would have been on short term visit abroad. From January 2015 till June 2022, on average 245 Bhutanese migrated per month. This figure (245) was until then the long term monthly migration. The monthly average has shot up rapidly. Since July 2022, the monthly migration averaged 3,120, but it rocketed go an ever high of 5,099 in January 2023 and 5,542 in February 2023. Whether it has peaked or not remains to be seen.

In total, 50,125 Bhutanese has migrated over the last eight years by Paro International Airport. They had migrated, as declared in exit forms, to 118 countries, including Azerbaijan, Belarus, Chad, Egypt, Gabon, Jamaica, Kiribati, Lebanon, Nauru, Papua New Guinea, Serbia, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zimbabwe. But this – 50,125 – number does not include those who would have migrated before 2015 as well as those who migrated through land routes in southern Bhutan. It is highly plausible that the total number of migrated can be over 65,000, if we could consolidate information from all sources. However, we should not be fixated on this number as it is not static. As long as migration continues, this number will be attained and crossed. Bhutanese working in the US, Canada, India, Bangladesh, Nepal and several other countries are most probably underestimated in the current data. Due to the limitation of entry and exit data, the current data, for example, show 15,390 Bhutanese are in India, 252 are in Bangladesh, and 1,946 Bhutanese are in Nepal.

The median age of Bhutanese at the time of exit is 29.71% of those who have migrated are below 35 years of age. However, there are also median age differences among destinations. For Australia, the median age of migration is 28 while the median age of 2,886 migrants to Kuwait is 24. Among females who migrated, 74% are 35 years or below. Among males who migrated, 66% are 35 years or below. In terms of gender, female migrants form 51% of the total. But this should not lead us to expect that in every place and country that the Bhutanese migrate, there is gender balance. Those who migrate to the Middle East, Canada, and the UK are predominantly female and young. 52% of the Bhutanese migrants in Australia are female, but this ratio is a result of paired migration through ‘partnership’, which does not result in reproductive or conjugal relationship.

Increasingly younger Bhutanese have been going abroad. Delay in the marriages among this otherwise fertile group caused by working abroad will lower the number of children born. Population growth will become negative faster than we realise. For those migrants who strike spousal relationship abroad, how their new family members will be enrolled as Bhutanese citizenship will become a familiar issue.

Public servants’ migration

Of particular interest among the public servants is their resignation and migration.

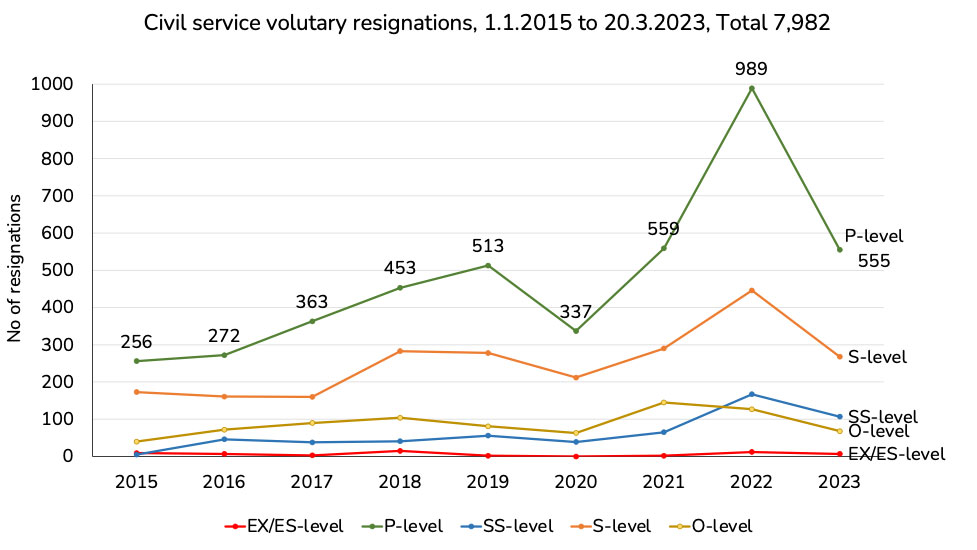

There is no consolidated data on resignation and migrations from Druk Holding and Investments Ltd (DHI), and state owned enterprises (SoE) as there is in the Royal Civil Service Commission (RCSC). RCSC data series on this topic begins from 2018 onwards. There has been voluntary resignations, with a long term average of 64 civil servants per month, between January 2015 to May 2022. In contrast, between June 2022 to February 2023, the number of voluntary resignations among civil servants rose to 234 per month. In April 2022, transformation exercises led to managing out of certain executives, managing in of others, followed by assessments of top level professional category (P1). New fiscal, administrative, and personnel measures, laced with bureaucratic centralistic tendencies, spawned a confounding sense with respect to some areas and energising mood in other areas among public servants. Overall, public servants sensed more uncertainty ahead. These and other measures influenced or tipped certain civil servants to voluntarily resign against a backdrop of huge income prospect if they migrate. Effects of uncertainty is more psycho-social and wider, beyond affected individuals.

The number of voluntary resignations in the civil service escalated in 2022 from 123 in June, 160 in July, 191 in August, 146 in September, 155 in October, 153 in November, to 362 in December; and 435 in January 383 in February 2023. The number of voluntary resignations in the civil service rose from 1,061 in 2021 to 1,741 in 2022. In 2023, the number of voluntary resignations stood at 1,005 just for the first three months of the years.

The number of voluntary resignations has been greatest among P-level civil servants. P-level resignations rose from 546 in 2021 to 977 in 2022. In the first three months of 2023, there were 552 P-level resignations.

Similar pattern is observable in voluntary resignations in the DHI companies, SoE companies and autonomous organisations delinked from the civil service. In 2022, 56 staff left DHI, 55 staff left Bhutan Power Corporation, 35 staff left Druk Green Power Corporation, 43 staff left Bhutan Telecom, and 36 staff left Natural Resource Development Corporation. Voluntary resignations of 3,705 public servants, including civil servants, who had worked for less than 20 years and who were members of pension fund led to withdrawal of Nu 1.944 billion from National Pension and Provident Fund.

Healthy slimming is always an aim of personnel management, but unplanned migration leaves disorder in its wake. I heard anecdotally that out of 30 teachers in a school in the outskirt of Thimphu city, 20 were waiting for their IELTS results. Should all 20 get successful results, the school will be largely enfeebled. This represents a case where there is inevitable tension between individual success to migrate and earn more, and the quality of public services. Private cash flows alone cannot resolve the troubling situation. Higher earning or remittance in this case will enhance private goods such as housing and other assets for the individuals along side deterioration in public goods and services. A nation is defined by how good its public goods and social welfare are. Private goods are less binding as a nation.

Migration as proportion of district population

Corroborated by a comprehensive data on applications of clearance certificates, that is available since January 2021 with the Royal Bhutan Police, there has been a surge in migration after Covid-related restrictions on movements were eased towards the end of March 2022. Made visible by the changes in the volumes of clearance certificates issued, the migration wave picked up again after certain banks resumed giving education loans for those going abroad.

Using data on applications of clearance certificates as proxy, we can draw inference on the number and proportions of people migrating from each districts. 90% of those who apply for clearance certificates succeed in getting visas and migrating. There has been migration abroad from all districts, with bigger districts in general sending more migrants abroad. 3,876 people out of population of 77, 717 in Trashigang had applied for security clearance while only 111 people out of total population of 3,422 of Gasa had. As a percentage of the district population, people from relatively wealthier districts migrate, by applying for clearance certificates. As a proportion of district populations, 11.8% of Thimphu, 9.4% of Paro, 7.9% of Bumthang, 7.3% of Haa, 6.8 % of Punakha have been issued clearance certificates, indicating that migration attempts were made more from commercial and urbanised districts. A thinning of population in the commercially advanced districts will result in tightening of availability of workers and higher wages. As wages in these places rise, more workers from the interiors parts of rural Bhutan will migrate domestically. Farming, which is labour intensive, will be hurt. Leaving behind the elderly in depopulated rural villages appears a possibility, and we must act against this rather grave outcome.

Push and pull factors

There has been both push and pull factors behind migration, with different degrees of influence depending on motivations and circumstances of migrants. An online survey confirmed predictable, leading pull factors such as higher income, better economic opportunity, greater financial security, more secure future, higher living standard, access to better education, etc. The online survey also pointed out that 63% of migrants aspire to permanent residency, showing no immediate desire to rush back home. The push factors can be reverse (mirror image) of pull factors. But the online poll adds a distinctive set of push factors. The poll cited job insecurity, lack of career progression, poor system or poor working environment, lack of recognition, greater work load due to diminished staffing, negative impacts of reform, peer pressure to migrate, and high cost of living among push factors.

Given the Bhutanese disdain for overt criticism, a respectful style of communicating difficult issues is reflected in the online responses. It is characteristic of Bhutanese to make, if at all, only oblique comments and very mild reservations on public policies. Yet the push factors mentioned by the respondents contain subtle statements towards decision makers including non-national ‘consultants’ who have featured in the highly polarising non-formal conversations among the public on some of the impacts of recent reform. More objective and wider discussion is fundamental to making of good public policies because it opens ways for unconsidered options and greater range of ideas that can often lie beyond members of mediocre committees. The aims and aspirations enunciated by His Revered Majesty for the country commands universal respect. Toward these visions, we have to keep our eyes on the strategy to reach them, methods and modality of implementation and, above all, the quality of people who have the capacity to flesh out details. Any imaginaire is revealed only in the grasp of details. Even a vision of a great city can be fulfilled only through an immense assembly of aesthetic, architectural and engineering details. We need foot soldiers of details to fulfil the vision of His Revered Majesty.

In the foreseeable future, average earnings in our country will be far behind that of Australia or Canada. If earning is the predominant preference to be maximised, migration will not peter out anytime soon. On the other hand, migrants living abroad experience lower wellbeing in circumstances other than financial matter. The government could focus on this missing wellbeing aspects for migrants – our citizens.

Migration, especially from the public service, brings up the issue of maximising personal income versus commitment to the development of the nation. Commitment orients people towards social welfare or collective good, even though it might go against ones narrow self-interest. This might include accepting lower income. But the lower income does not mean living on the edge without being able to square cost of living. We need to address the cost of living issue as an economy wide topic. Welcome though the salary increase is for public servants, it will not ameliorate inflation as a whole for all citizens. In fact it will propitiate the public servants while fueling wage push inflation. Having tackled inflation as a whole, it is desirable to revive and refresh commitment to the nation development among the public servants on the eve of the next five year plan. They have become less in number and has to do more. Uncertainty they feel can be transmitted to society in general. All Bhutanese, wherever they are, will and should bear commitment to national development and certainty of a nation of great wellbeing, the nub of national addresses by His Revered Majesty.

Contributed by

Karma Ura