Chencho Dema

PUNAKHA — Punakha valley, often celebrated as Bhutan’s rice intestine due to its rich agricultural heritage, is currently grappling with a disheartening predicament. Startling records from the dzongkhag agriculture sector reveal that over 1,455 acres of land, encompassing both wet and dry areas, have been left fallow across the 11 gewogs of the dzongkhag.

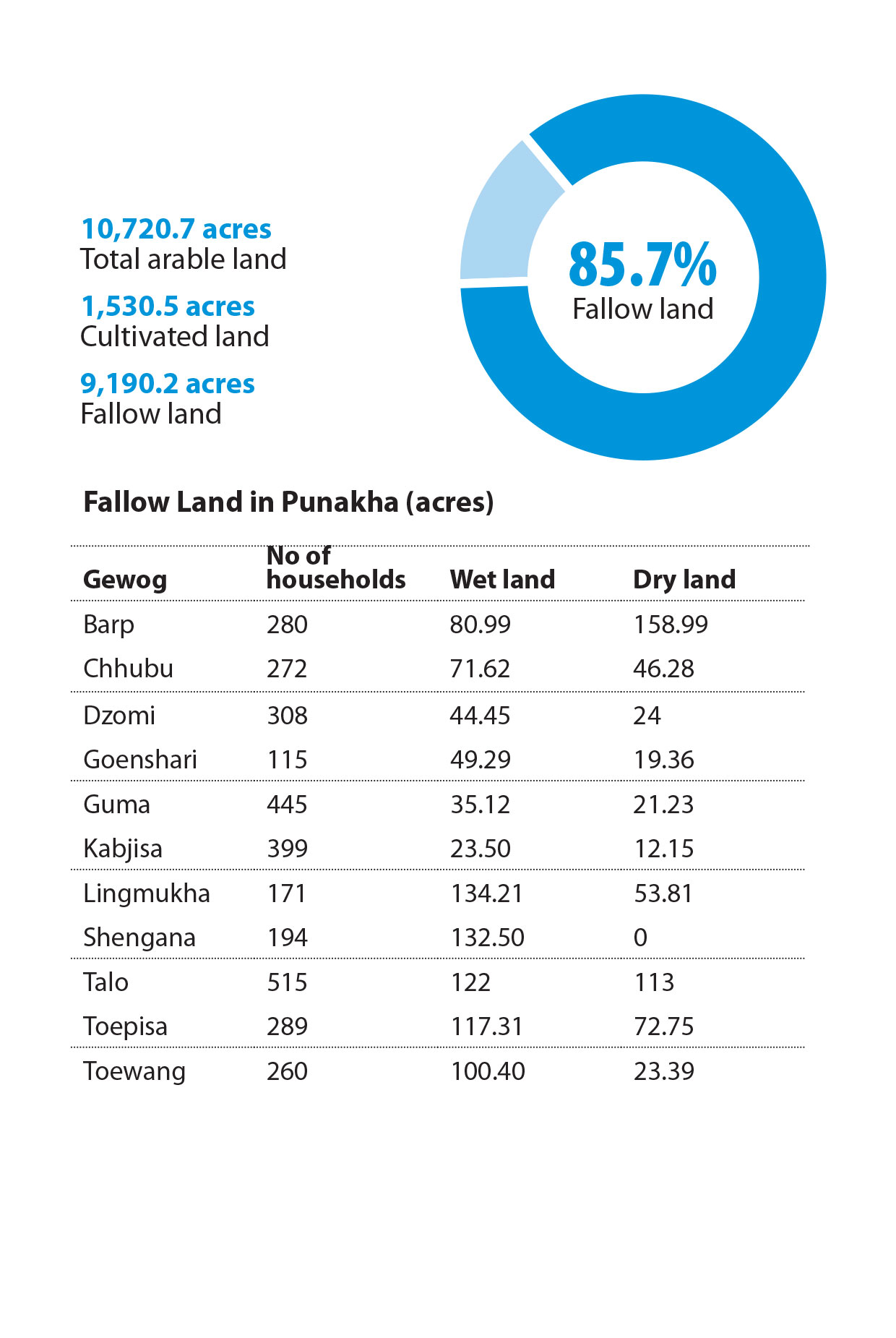

The gewogs include Baarp, Chhubu, Dzomi, Goenshari, Guma, Kabjisa, Lingmukha, Shengana, Talo, Toepisa, and Toedwang.

The reasons behind the abandonment of these fields are diverse. According to the gups, some of the primary factors contributing to the decision to leave land fallow in their respective gewogs include a lack of irrigation water, declining population, human-wildlife conflicts, labour shortages, high daily wage rates, elderly individuals unable to work in the fields, and migration.

Punakha region boasts a total land area of 8,373.2785 acres of wetland and 2,347.423 acres of dry land. However, out of this expanse, a staggering 7,457.686 acres of wetland and 1,732.472 acres of dry land remain uncultivated. Additionally, 143.214 acres are designated as orchards.

The number of households across the 11 gewogs stands at 3,248, with Talo Gewog hosting the highest number of households at 515, followed by Kabjisa with 399, and Dzomi with 308. Conversely, Goenshari is the gewog with the least number of households, with only 115, trailed by Lingmukha with 171, and Shengana with 194. Interestingly, Lingmukha also boasts the largest area of fallow wetlands, totaling 134.205 acres, followed closely by Shengana with 132.5 acres, and Talo with 122 acres.

Sonam Tobgay, Lingmukha gup, attributed his gewog’s prominence on the list of gewogs with the most fallow land to the declining population, as well as other factors such as conflicts with wildlife and a shortage of irrigation water.

“Although there is no shortage of irrigation water in my gewog, a significant amount of land remains uncultivated due to a dearth of villagers available to work in the fields. Today, we have more land than people,” said Samten Phuntsho, Shengana-Bjemi gup.

Furthermore, he expressed his concerns that the situation would only exacerbate in the upcoming years, with little hope for a solution. While he acknowledged that the problem could potentially be remedied if the government allocated sufficient funds for electric fencing and uninterrupted water supply for irrigation, he is sceptical about any significant improvements materialising.

Among the fallow lands, Baarp Gewog claims the highest acreage of uncultivated dry land, amounting to 158.99 acres, followed by Talo with 113 acres, and Toepisa with 72.75 acres. On the other hand, Kabjisa Gewog stands out with a mere 23.5 acres of fallow wetland, closely trailed by Guma with 35.13 acres, and Dzomi with 44.45 acres. Notably, Shengana takes the lead in terms of zero acres of fallow dry land, while Toedwang follows with 23.392 acres, and Kabjisa with 12.15 acres.

Cheychey, mangmi of Barp Gewog, admitted uncertainty regarding the reasons behind the community’s decision to leave their land fallow but suggested that lack of irrigation water might be a contributing factor. “When it’s time for them to harvest the crops they’ve worked so hard to grow, they often find their harvests damaged or devoured by wild animals. This unfortunate reality has led many to abandon their land.”

Chador, former gewog administrative officer of Talo, shed light on the demographics of the gewog, stating that a majority of its residents are elderly and unable to engage in fieldwork. Additionally, the expenses associated with agricultural labour, including daily wage rates and equipment rental fees from the gewog, prove to be financially burdensome and are not sufficiently covered after the harvest.

Gup Tshering Penjor cautioned that although the current percentage of fallow land stands at only 15-20 percent, the number could rise to at least 80 percent in the next decade.

He attributed this trend to the preference of individuals to leave their fields unattended and instead seek employment in others’ fields due to the high daily wage rates. “The majority of the youth have either migrated abroad or found employment in urban areas, leaving only the elderly who are unable to work in the fields.”

Moreover, Tshering Penjor emphasised that many farmers cannot afford the expenses associated with machinery. For instance, renting a power tiller for an hour costs Nu 500, and a full day rental amounts to Nu 4,000.

Meanwhile, Wangchuk Dorji, Goenshari gup, attributed the fallow land issue in his gewog to labour scarcity and the migration of people to urban areas.

According to records compiled by the Punakha dzongkhag administration, the dzongkhag produces approximately 11,550 metric tonnes of paddy each year. However, the prevalence of fallow land raises concerns about future food security and the sustainability of agriculture in the region.