… compared to the in-kind tax people had to pay in the past

In the living room of a duplex in Semtokha, Thimphu, a group of women spanning generations engage in lively chatter about the recently implemented revised property and land tax.

Among them sits Aum Zam, aged 86, the eldest with her gray hair a testament to the decades she has witnessed. She reminisces about a bygone era, a time before 1970 when the taxation landscape in Bhutan was vastly different.

The octogenarian is not complaining of the revised taxes. She had witnessed worse. Back then, residents of Thimphu, Punakha, and many other dzongkhags found themselves subjected to a taxation system that demanded both tangible goods and labor contributions. Aum Zam recollects the taxing times when levies were extracted not in cash, but in the form of physical efforts and resources.

Today, as property tax becomes the talk at any gatherings, Aum Zam, whose descendants own multiple buildings and acres of land in Thimphu, welcomes the change. She believes it’s a fair trade-off, acknowledging that landlords now contribute a modest sum to the government coffers, compared with the earnings from their properties.

A prominent businessman in Thimphu used to pay around Nu 0.5 million until last year for his properties. With the revised rates, the tax on his property is estimated close to Nu 2.1M this year. “I think it is worth paying given the value of land and property in Thimphu,” he said. “Property tax is not a new concept; it was there since our parents’ time,” the businessman recalls. However, the amount was negligible.

Recalling the hardships of yesteryears, Aum Zam paints a vivid picture of a time when tax payments meant toiling to gather soot from kitchen fires and traditional oil lamps, commodities used in the production of traditional ink to write mostly holy scriptures. Back in the 1950s or 1960s, she recalls, taxes were paid through sweat and labor, regardless of one’s ability to meet such demands or without any source of income.

In-kind taxation

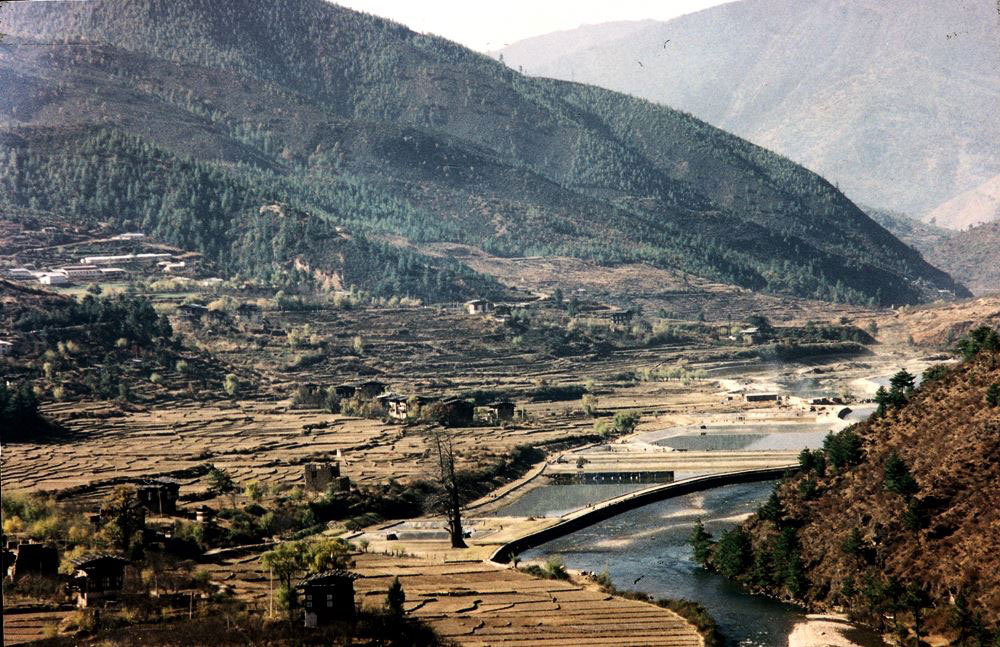

Before the 1960s, taxes were collected in kind and in the form of labor contributions.

People were taxed on food grains like wheat, buckwheat, and rice, mustard oil, butter, salt, yak meat and beef, textiles of raw silk, cotton, wool, the bark of paper plants, ash, pig iron, lac, firewood, animal feed and fodder tax, dried chilies and chili seedlings, bamboo baskets, mats and ropes, leather bags, and hide. The hide of cattle was used for making glues to be used in wall paintings and religious items like drums.

The type of in-kind taxes imposed on the people was based on what they produced. For example, the collection of in-kind taxes like cotton and raw silk textiles was specific to Zhemgang and Trashigang, yak meat to Paro, Haa, and Thimphu, and wool tax to the people of Bumthang.

Residents of Punakha were required to contribute five bunches, poorer farmers, two and a half bunches of chili seedlings to the Dzong for cultivation on the land belonging to monasteries.

People of lower altitudes of Wangdue had to provide rice in lieu of shingthrel (wood tax) for the Punakha and Wangdue dzongs. The people of la-gong-sum (residing in the high altitudes) were required to supply dey (bark of paper plants) and bamboo products in lieu of shingthrel.

In his book titled “The Hero with a Thousand Eyes,” Dasho Karma Ura talks about the entangled web of taxation, where he mentioned that a whole range of edible and non-edible things were paid in-kind, as wherewithal for all officials working in the dzongs.

Each dzong (fortress) like Jakar, Wangduephorang, Trongsa, Trashigang, Lhuentse etc, was administered by the top layer of officials consisting of a dzongpon (fort governor), who was supported by droenyer (guest master), zimpon (chamberlain), and nyerchen (chief steward), followed by the prominent post holders like gorap (gate controller), shanyer (meat caretaker), tsanyer (fodder caretaker), tapon or horse master, and banyer (cattle master).

As Bhutan’s taxation system evolved, transitioning from in-kind and labor contributions to cash payments, Aum Zam’s reflections offer a glimpse into the socio-economic transformations that have shaped the nation’s fiscal landscape.

Administrative and tax reforms

His Majesty the Third King initiated both administrative and tax reforms with the merger of some drungkhags and a few drungkhags abolished, and the tax system changed to reduce the burden on taxpayers.

The first session of the National Assembly (NA) held in autumn 1953 resolved that tax would be realised only on the actually cultivated land. The decision was taken following the submission made by the people of Thimphu that they couldn’t pay taxes in kind for all the lands possessed by them and large areas of land remained vacant due to a shortage of farmhands.

The new property tax today requires a landowner to pay a vacant land tax of 15 percent on the amount of land tax.

Taxes in kind were gradually phased out and replaced by nominal monetised tax on land, property, business income, and consumption of goods and services.

The NA in 1964 introduced the payment of taxes by cash.

The first major tax reform was initiated in 1989 to take stock of various tax measures, develop a coherent and rational tax system, establish a system of tax in a fair, equitable, and efficient manner that minimizes the need for frequent change, and fully document the system in a way that promotes taxpayer awareness.

The government also carried out tax reform in 1992 for the rationalisation of the tax structure, expansion of the tax base, and simplified administrative procedures for compliance and transparency.

The revised tax rates may be seen as a burden, but going by what senior citizens say, it is nothing compared to the taxes of the past. “As long as we have income, paying taxes is not a burden. We had to, in the past, worry about producing the tax item before paying them.”

Contributed by

Rinzin Wangchuk