Thukten Zangpo

The government plans to borrow more and put the money into reviving the country’s economy, ailing due to the Covid-19 pandemic, as a fiscal measure.

According to the National Accounts Statistics report, Bhutan’s economy measured in the nominal gross domestic product (GDP) saw a contraction of -10.08 percent in 2020 from the previous year’s 5.46 percent growth.

The National Budget Report for the fiscal year (FY) 2021-22 targets a minimum of 3 percent economic growth by June 2022.

Finance Minister Namgay Tshering said that the nominal GDP loss incurred in six months of 2020 amounted to Nu 5B, and the government needed to pump money into the economy to offset the loss.

He added that the government will borrow for the project-specific activities that would be self-liquidating. “The government will invest, not spend.”

Lyonpo said that infrastructure development and human resource development would be the government’s priority. The government’s spending contributes to almost 37 percent of the GDP.

Although the government has not yet decided how much to borrow, he said that Nu 6 billion (B) has been mobilized from grant programmes for the fiscal year (FY) 2021-22 and additional borrowings to be met from the domestic financial institutions through short-term treasury bills (T-bills) and the sale of government bonds.

Another avenue the government is looking to borrow from is the European Investment Bank. “It would be suicide if we are conservative and think that there will be undue debt burden in the future for our future generations,” he said adding that Bhutan will be left behind by a country of similar size, under-developed, and developing countries after five to 10 years down the line.

The government will study the repayment situation and forecast risk with the currency fluctuation when borrowing, the minister said.

A professor of economics at Royal Thimphu College, Sanjeev Mehta, said that the borrowings, especially external borrowings, are important to mobilise additional financial resources for development and support economic growth.

“So far as the loan is used for productive purposes and the rate of return on this investment exceeds the repayment rates, there is no issue,” he added.

The projected fiscal deficit of the 12th Five-Year Plan (FYP) was Nu 29B of the total budget outlay of Nu 310B due to a high level of investment in the economy to support economic recovery.

Bhutan’s development partners have committed about USD 865 million (M), which is equivalent to Nu 63B for the 12th FYP. Out of this, Bhutan received Nu 31B of the total development partner’s support.

The fiscal deficit had risen to Nu 11.139B in 2020-21 compared to Nu 545M in FY 2017-18, mostly on the account of borrowings for hydro-related loans.

Debt situation

The national debt of the country has been growing over the years. It was recorded at Nu 240.897B accounting for 127.4 percent of the nominal GDP as of September 30 of this year, according to the Ministry of Finance’s (MoF)public debt situation report. The debt at Nu 33.07B at end of the 9th FYP (2007-08) tripled to Nu 101.31B at the end of 10th FYP (2012-13) and increased to Nu 185.312B at the end of 11th FYP (2017-18) because of hydro-related borrowings.

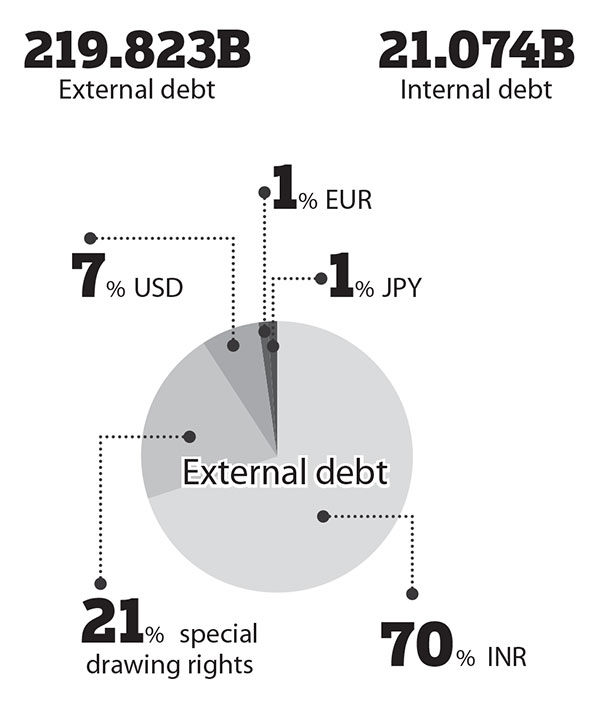

As of September of this year, the external debt comprised 91.3 percent of the total debt at Nu 219.823B, while the domestic debt at Nu 21.074B accounted for 8.7 percent.

Hydropower-related borrowing makes up the major portion of the total debt Nu 161.651B, and almost three-fourths (73.5 percent) of the total external debt. Meanwhile, the non-hydro debt stands at 58.171B, which is 30.8 percent of the GDP.

Hydro-debt comprises six hydropower projects, namely Punatshangchhu-I (Nu 48.274B), Punatshangchhu-II (50.632B), Mangdechhu (Nu 45.952B), and Nikachhu (Nu 3.145B), and Dagachu (Nu 7.384B).

Moreover, 12.8 percent of the total external debt is for policy and budget support from the World Bank and Asian Development Bank (ADB).

The remainder is from borrowings for financing infrastructure development in the country, such as rural electrification, road connectivity, trade infrastructure, and urban development.

The external debt also includes borrowings from India for Standby Credit Facilities of Nu 7B availed from the Indian government during the Rupee crunch in the year 2011-12.

Seventy percent of the total external debt Bhutan owes is to the Indian government, followed by 14 percent to ADB and 12 percent to World Bank.

The rest, about 4 percent to the International Fund for Agricultural Development, Japan International Cooperation Agency, the Austrian government, and SAARC development fund.

A major portion (70%) of the country’s external debt is denominated in Indian Rupee (INR), followed by denominations in special drawing rights (21%), USD (7%), and EUR and JPY at 1% each.

Meanwhile, the total domestic debt stood at Nu 21.074B, accounting for 11.1% of GDP and 8.7% of total public debt as of September 30 of this year.

Debt threshold and risk

Article 14 (5) of the Constitution of Bhutan states that the government shall ensure that the servicing of public debt will not place an undue burden on future generations.

According to Bhutan’s Public Debt Policy 2016, for hydropower external debt, the annual debt service for the total external debt shall not exceed 25 percent of the total exports of goods and services.

The total external debt service to exports of goods and services was 11.7 percent in the FY 2020-21 that is below 25 percent, according to the public debt situation report.

However, it is projected to rise to 21.2 percent in FY 2021-22 because of full annual debt servicing for the Mangdechhu Hydropower Project and liquidation of a Standby Credit facility of Nu 4B, despite the increase in exports.

For hydro-debts, the debt service coverage ratio for hydropower projects should not be lower than 1.2, as per the Public Debt Policy.

The debt service coverage ratio measures coverage of annual hydropower debt service by operating profits of hydropower plants.

The Budget Report 2021-22 stated that the hydropower debt service coverage ratio was high at 14.1 in FY 2019-2020.

“The high ratio was due to a considerable drop in hydro debt servicing in FY 2019-20 after the Tala Hydro-electric Project Authority loan liquidation in December 2018, while hydro export revenue significantly increased after the Mangdechu hydro-project (MHP) commissioning in August 2019,” it stated.

It added that the ratio is expected to drop to 3.2 in FY 2021-22 due to the full annual debt service of MHP and is projected to improve slightly in 2022-23 due to an increase in hydro-revenue after PHPA-II commissioning in December 2022 and drop further with the start of the PHPA-II debt servicing.

“The hydro debt service coverage ratio is projected to remain above 1.2 in the medium term,” it stated.

The non-hydro debt at 30.8 percent of the GDP is within the 35 percent threshold prescribed by the Public Debt Policy 2016.

In FY 2021-22, the projected fiscal deficit was 8.59 percent of GDP due to a high level of investment to support economic recovery. It saw above the fiscal target of 5 percent of GDP.

The fiscal target was set to ensure sustainable fiscal balance and debt sustainability through optimal utilization of the budget, besides mobilizing additional resources.

In the MoF’s public debt situation report, it was stated that the overall risk of the debt is low and manageable, given the major portion of external debt for commercially viable hydropower projects, with a ready market in India and 91.2 percent of the hydro debt denominated in INR.

The MoF estimated that the average time to re-fixing the debt at 10.3 years. “The interest rate risk was low given the low portion of the variable interest rate since the debt with a fixed interest rate constituted 95.2 percent of the total public debt,” it stated.

The MoF also estimated that the average time to maturity (ATM) of the debt at 10.8 years, and about 10.8 percent of the debt will mature in a year and that the long ATM and low level of debt maturing in a year indicate that the refinancing risk is low.

With more than 80 percent of the domestic debt maturing within a year, domestic debt could pose huge refinancing and interest rate risks if banks do not have adequate liquidity in the coming months to refinance the maturing T-Bills, it added.

On the other hand, the recent Royal Audit Report 2020-21 cautioned on the rising debt that would have a long-term negative impact on economic sustainability.

It stated that the high proportion of the internal revenue is being consumed by the recurrent expenditure showing the dependency on grant borrowings.

“The grant being donor-driven and outside the government control and not certain both in terms of timing and cash flows, a judicious fiscal policy is imperative,” it added.

The country’s internal revenue at Nu 35.855B was enough to meet the current expenditure (Nu 31.889B) in the FY 2020-21.

“The hydropower-related debt is self-liquidating in nature because of its ability to repay through the export of hydroelectricity to India,” Sanjeev Mehta said.

However, he added that the ongoing project delays have resulted in cost escalation, 60 percent of which translates into an increased debt burden due to aid and loan proportion of the assistance.

Also, he said that the closure of existing power plants in the recent past has also affected the export earnings and consequently exacerbated the repayment burden. “Climate change-related impact on river water flows is also a potential challenge,” Sanjeev Mehta said.

The Opposition Leader, Dorji Wangdi, said that despite huge borrowings, there was no result in terms of economic progress and infrastructure development.

He added that the rate at which public debt has grown is alarming and the government should have done better with public finance management.

A study by the World Bank found that if the debt to GDP ratio of a country exceeds 77 percent for an extended period, it slows economic growth.

“If the debt is above this threshold, each additional percentage point of debt costs 0.017 percentage points of annual real growth,” it stated.

When can the government borrow beyond the threshold?

According to the Public Debt Policy 2016, if the government has to borrow beyond the thresholds, the government is allowed during times of economic crisis and other unforeseen exigencies and extraordinary circumstances.

It added that when the government has no other means but to raise additional debt to maintain socio-economic stability.

However, the government has to issue a formal directive to the MoF to raise the additional debt and inform the next sitting of Parliament.

Edited by Tshering Palden