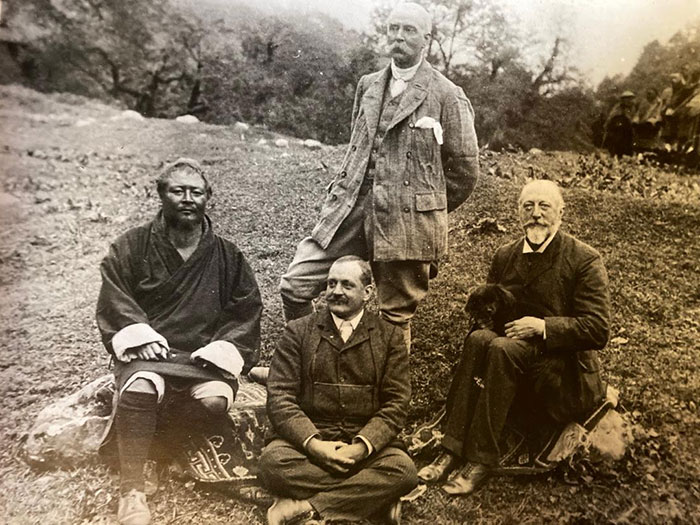

J.C White (Standing), Gongsar Ugyen Wangchuck, Major F.W Rennick and A.W Paul.

(Photo: J.C White’s private collection)

The rendezvous of Gongsar Ugyen Wangchuck and J.C.White

In 1906, Gongsar Ugyen Wangchuck and John Claude White, met privately in Lhalung monastery. The monastery is in the Lhodrak province of southern Tibet. Considered as the main seat of Terton Pema Lingpa, this great monastery also became the seat of the successive incarnations of the Terton and his son.

In 1906, Gongsar Ugyen Wangchuck’s nephew (Yeshey Choden’s son) Tendzin Chokyi Gyeltshen (1894-1925) was being installed as the ninth Peling Sungtrul in Lhalung. The eighth Peling Sungtrul Kunzang Dorji Tenpe Nyima (1843-1891) was the Penlop’s teacher. In 1891, when the teacher died, the Penlop attended the funeral in Lhalung.

In 1906, the ninth Peling Sungtrul was twelve years old. He had trekked up to Lhalung from Bumthang for his installation ceremony and was waiting for his uncle, the Trongsa Penlop and J.C White to grace the occasion.

The British Political Officer and the Trongsa Penlop had already met three times previously. They first met in Tibet where both were active members of the 1904 Younghusband mission. In 1905, the Government of India had deputed White to present the insignia of the Knight Commander of the Indian Empire to the Trongsa Penlop for his services during the Younghusband mission.

After the investiture ceremony in Thimphu, the Penlop invited White, Major F.W. Rennick and his close friend A.W. Paul to Bumthang to meet his family. The Major was an Intelligence officer. Paul had retired from the Indian Civil Service and had travelled from England especially for the occasion.

The third time they met was in Calcutta. In 1906, the Trongsa Penlop was invited to the City of Joy to meet the Prince and Princess of Wales (later King George V and Queen Mary).

White’s Journey

The details of White’s and part of the Penlop’s journey are reflected in his official report No. 2680, written from his house in Gangtok on 19 July, 1906.

Like all formal reports of the time, the report is addressed to the Secretary to the Government of India in the Foreign Department. The subject was, “Report on tour through Bhutan to Gyantse via Dewangiri.”

As per this report, White, left Gangtok on 13 May. He arrived in Lhakhang Dzong (Khothing) in Lhodrak almost a month later on 11 June. The Penlop left Jakar on 1 June, 1906 arriving in Lhalung on 10 June.

From the report, we know that White entered Bhutan from Dewangiri (today Deothang) in present day Samdrupjongkhar. He took the train from Siliguri to Dhubri. From the hot plains of Assam, he rode the steamer up the Brahmaputra river to Guwahati and then trekked up to Dewangiri.

In Bhutan, thanks to his noble host and friend, White was able to visit many temples, monasteries, forts, factories and farms. He traversed the land with the assistance of guides and bearers, sometimes using elephants and yaks to get himself and his heavy photographic equipment around.

From Dewangiri, White trekked up to Trashigang and then on to Trashiyangtse. In Trashigyangtse, he visits the famous Chorten Kora chorten. He then halted in Singye Dzong before continuing on into to Tibet to reach Lhalung.

On 8th June, the officer arrived in Singye Dzong. White is probably the first westerner to visit the dzong and describes it. In his words, the small dzong was not worthy of the name but the location was worth the mention. He describes it as an unoccupied building, in ruins, situated on a fine rock.

As a colonial administrator by profession, he was quick to notice the absence of the Dzongpon. He was able to find out that the Dzongpon preferred to live in his house at the foot of the Singye Dzong.

Surprisingly White had already met the Dzongpon who had been the quartermaster of the Younghusband mission. White remembered him issuing rations during the Lhasa expedition. We find from White’s records that the Dzongpon had just been transferred to this post a year ago.

Despite the absence of the administrator, White commended the logistic arrangements. He says that after Singye dzong, his expedition changed transport and found everything ready and the change did not take long.

An engineer by training and photographer by vocation, White was particularly interested in bridges, buildings and roads. In his diary, he revealed his admiration for the ingenuity of the Bhutanese irrigation systems.

Along the way, White observed, recorded and photographed the health of our forest, the rich wildlife, geology, and geography. His Bhutan photos are among the most compelling visuals we have of that era.

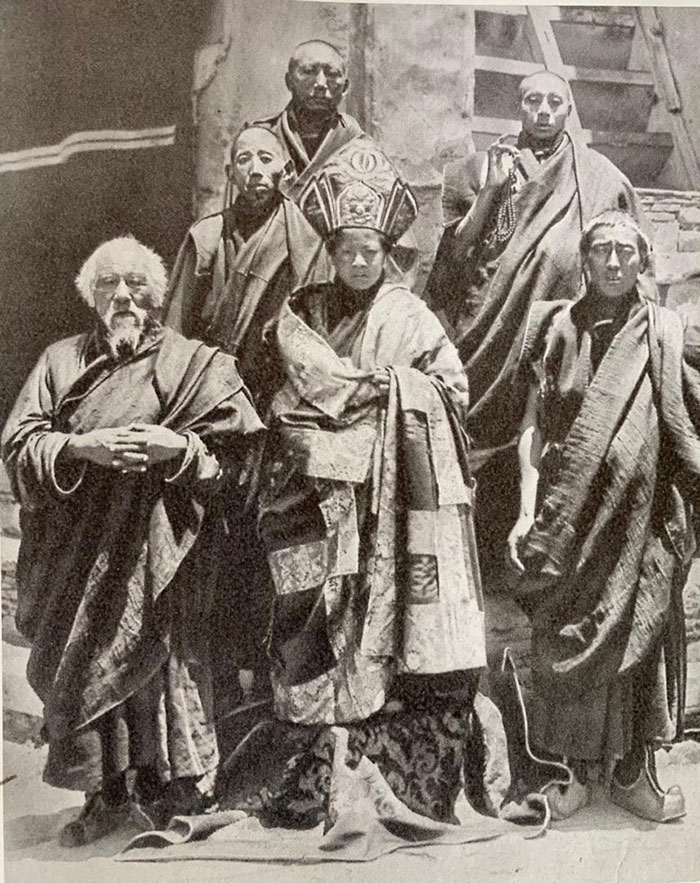

The Ninth Peling and his monks at Lhalung monastery in Tibet (Photo: J.C White)

Tibet

From White’s record, we learn that after almost being one month on the road, on 10th June, he crosses the Bod La (16,290 feet) which he describes as the boundary between Bhutan and Tibet.

The British officer was surprised with the reception he received in Tibet. His remarks, “I had hardly expected such a reception in Tibet but every one vied with one another to see that they could do to make me comfortable.” He took his reception as an indication that the Tibetans bore no ill-will on account of the Lhasa expedition.

The Meeting

On 11 June, the Trongsa Penlop received White at the Lhakhang Dzong. White recorded the day as, “Meeting Sir Ugyen again was a very great pleasure and we had a great deal to talk over.”

According to the reports, the next day, the two friends rode up to the Karchu monastery. White wrote that beyond getting a good view of Kulugangri mountain, there was nothing much of interest to be seen.

On the 13th, the two visited some hot springs in the morning. They also visited an old gold mine. It was said that these mines had been worked as recently as 12 years back by the Dzongpon who imported men from Tod (Western Tibet) for this purpose. Situated in an old river bed, the mines had been abandoned.

On the 16th June, the two friends marched to Lhalung. White noted details of the route. One entry states, “The road first took us straight down to the river a decent of 2,400 feet and then right up the other side going straight up the hill by a small zigzags which were very trying. It then wound round the hill sides for some distance and again down to the stream at Tuwa Jong (height 13,100 feet). This is fine building and built in the Tibetan style with the Jong situated at the stop of a very steep rock, below which is the monastery, also a fine building.”

The afternoon was hot on the day Trongsa Penlop and White rode to Lhalung. White said that he did not mind the heat of the sun as it was compensated for by the reception he received at Lhalung. The Trongsa Penlop’s nephew, the Peling Trulku, monks and head men of Lhalung had all come to receive them.

Delightful by the camp pitched in the monastery garden, White mentions of it in his notes. He says that everything for his comfort had been provided. He talks about his time sitting in the cool shade of the willows on the grass out of the glare and out of the wind, as the garden was surrounded by a wall.

On 18th June at the request of Trongsa Penlop, White stayed back. The two enjoyed another quiet day. They spent the morning receiving deputations from the Dzongpon of Tuwa Dzong, lamas of Lhalung and head men of Tuwa and Lhalung. The remainder of the afternoon the two spent talking about interesting subjects on Bhutan, such as road improvements and socio-economic developments, etc.

Two days later, on 20th June, they crossed the Ta-La pass (17,900 feet) which according to White’s record is the watershed between India and the Pho-mo-chang-thang lake basin. After camping at a yak station called Sagang, where they had a clear view right up to the snowy hills which form the Bhutan boundary.

From the top of the pass, they went their separate ways after the Penlop presented scarves of different colours. White records, “a large river runs into the west-end of the lake which takes its rise on the north of the snows which form the boundary between Bhutan and Tibet.”

On 22nd June, White crossed the Nelung pass and came down to Khangma, where he changed transport and came to Sewookgang. After spending three days at Gyantse he went to Phari and then to Gangtok where he arrived on the 6th July bringing to an end his almost two month exploration to eastern Bhutan.

Conclusion

They were several outcomes of the 1906 trip to Lhalung. Top on the list is forging the deeper personal relationship between the Trongsa Penlop the British Political Officer. The other outcomes were the introduction of vaccination in Bhutan. White travelled with a vaccinator. At the end of the journey, he had vaccinated at least 800 people against smallpox. At the Penlop’s insistence, White left his vaccinator in Bhutan to accompany the Trongsa Penlop to Jakar.

The trip also tested diplomatic relations and the position of the Penlop. The Tibetans’ objection at allowing White to travel through Southern Tibet was put to rest with a tactful response. It was clear that the Trongsa Penlop enjoyed a good priest-patron relationship with some of the leading monks but had hardly any relationship with the Tibetan government.

The other outcome is the photographs taken during the trip. White was an amateur photographer but earned quite a reputation for it. His style of using photos to illustrate his reports added perspective and texture to them. Thanks to White, we have a photo of the 12 year old ninth Peling Sungtrul. Taken at Lhalung, the Trulku is shown dressed in his ceremonial robes surrounded by five monk attendants.

After the Lhalung trip, the two great men meet for the fourth time. In 1907, the Government of India sent White up to Bhutan to attend the coronation of the Trongsa Penlop as the first hereditary Druk Gyalpo.

Contributed by

Tshering Tashi