Politics of Forest Cover

There is a problem with forest cover reporting in the country. The figure is sometimes reported higher and other times lower. It confuses people and also can have policy and management implications. The problem has origin in 2005.

In 2005, the Department of Forests reported in Kuensel that the true forest cover in the country was 64.35 %, not 72.5 %. The Department had taken out the 8.15% of shrub sub-class from the forest definition. That same year, the revision of the 1995 Land Cover report was being finalized, and it showed, the forest cover had increased from 72.5 to 81.5%. For some reason, the good news was not good news for the Department. They pushed back on the accuracy of the figure in the internal consultation meetings with stories of forest damage, destruction and loss. The report was never released. A few years earlier, the Department with the assistance of a donor had undertaken a land cover study. It showed the forest cover at 79.59%. This report too was never released.

Denying the high forest cover figure by the Department may have roots in the history of colonial forestry. The colonial Forest Department in India always painted indigenous forests in dire conditions due to wanton destruction by indigenous people and saving the forests their duty. They thus pushed forward and thrived on an ‘environmental crisis’ narrative. Our own department perhaps subconsciously saw the extremely high forest cover figure as dissipating and weakening their ‘forest crisis’ narrative.

The Department today defines a forest to mean trees alone. The shrub which was until recently a forest sub-class is now removed from the forest definition. The forest cover figure earlier constituted the total area of both trees and shrubs. The shrub sub-class actually contains a lot of trees. According to the National Forest Inventory Report 2016, there are over 51 million trees outside the Department’s ‘trees alone forest’ category, and these trees are certainly mostly on this shrubland.

The current official forest cover figure is 70.77%. It leaves out the shrub cover of 9.74%. In the old reporting, the forest cover figure would be 80.51% (trees + shrubs). The Constitution does not have a forest definition of its own but it states that the State shall maintain a minimum of 60% forest cover to ‘conserve the country’s natural resources and to prevent degradation of the ecosystem.’ The word ‘ecosystem’ certainly calls on the State for a forest definition with a scope and extent beyond the trees.

Bhutan’s Forest Law Has Root in Colonial Forest Law in India

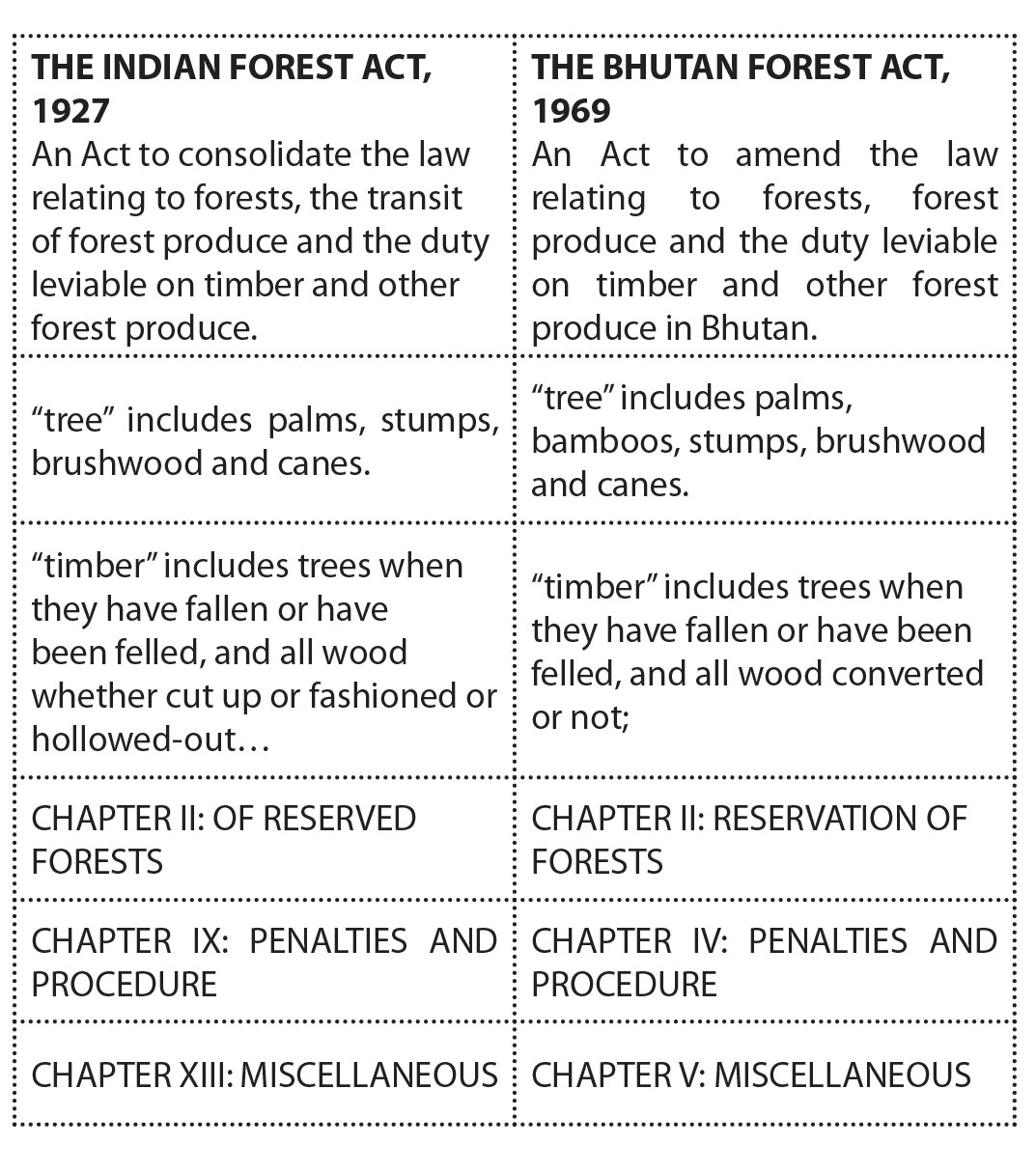

The Bhutan Forest Act 1969 was largely a copy and paste of the colonial era forest law in India, The Indian Forest Act 1927, chapter for chapter and sentence for sentence (see table).

The primary motivation for European colonialism was to increase their wealth and power and to exploit the natural resources in their colonies. The history of colonialism is one of brutal subjugation of indigenous peoples.

As the British gained control of one province after another in India, one of the first things they did was to proclaim the forest of the province as the property of the Government and then rolled out forest rules prohibiting the local people from cutting down trees, and instituting duty on timber. They established a forest department with the expressed aim of ensuring the sustained supply of timber required to meet the empire’s growing demand for timber for navy, army, railways, public works, and revenue generation.

The colonial Forest Department thus put trees at the centre of the policy objective; engaged in an exclusion policy of keeping away local people from forest areas; treated forests as a source of revenue to the state and not to meet the needs of the people, and took it as a duty to manage the forests for the benefit of and on behalf of the people and state. The forest rules caused great difficulties for the local people as they lost their customary rights, and as the rules put restrictions on their cultural farming practices and dependence on the surrounding forests.

Bhutan enacted a forest law in 1969 and it was the first modern legislation in the country. A Bhutanese scholar undertaking a historical analysis of public policy formulation in the country noted that with the Forest Act, there emerged a foreign concept of the state as an owner of national property especially any land not specifically registered privately. The 1969 Forest Act provided the State with the ultimate property rights over forest and forest produce. Forest produce was defined as constituting ‘everything below and above the forestland’. The State particularly laid emphasis on timber as it claimed ownership of all timbers found adrift, beached, stranded or sunk, and all trees, timber and other forest produce even on private lands. And, any person found settled in a forest was to be evicted forthright and his crop and any building erected to be confiscated. And, cattle were too to be confiscated if found trespassing in a forest. The State began the system of rationing the timber requirements of the people and levied duties on forest produce in the form of royalties. The State-controlled, restricted and prohibited the collection, movement and sale of the many economically important plants and medicinal plants which had some sale value in the market.

Prior to the Act, forests were free to all people to take what they required for their simple rural life, and in cases of valuable common property resources like cattle grazing ground or locally important forest produce e.g., bamboo, members of another community could not get rights to them. Otherwise, there could be sanctions from higher powers or matters dealt with as per the customary rights.

The 1969 Forest Act was replaced in 1995 by the Forest and Nature Conservation Act. Except for the chapter on Social and Community Forests, the new Act is an even bigger colonial monster with people now requiring a government permit to enter, camp, hike, taking photographs, video or sound recording and conducting any scientific research in forest. The colonial world view of power and nature continues to dominate the official forest narrative in a reinforced manner.

The Forest Department in 2014 registered a total of 935 forest offences in the country, collected a total fine amount of Nu 30 million of which Nu. 14 million was paid as rewards to the informants. This from the point of the Department is considered a tremendous success story of their forest policing responsibility. However, the common people find it difficult to understand why their own Government would plant spies amongst them and criminalise their forest-dependent livelihoods.

Decolonising Forest Policy

Forests are to the Bhutanese the centre of their world and the source of their spiritual, social, cultural and material wealth. Landscapes are inscribed with sacred sites and deities. Bhutan’s forest law should be born out of this sacred relationship between people and nature, indigenous knowledge of the people and the importance of forests to people’s livelihoods, not drive a wedge between people and forest as the current law does.

Once condemned by western science the indigenous knowledge is primitive and backward, western science is turning today to indigenous people for help in many of the global environmental issues viz., land management and biodiversity conservation. Some countries have started the reintroduction of fires on the land to prevent climate change-induced catastrophic fires occurring in future. And, there is greater biodiversity on lands managed by indigenous people.

Property rights when recognized by the state are important components of sustainable management of resources by rural communities. The centralization policy leads to loss of local property rights and associated lack of incentives for collective action or more incentives for short-term optimising behaviour.

Law plays a direct role with regard to social change by shaping a direct impact on society. The 1995 Forest Act is now over a quarter-century old and outdated. In the past we may have innocently believed the colonial knowledge as superior and modern, thus we adopted their world view and law. We can do a better job now drafting a forest law that is indigenous and serves better the Bhutanese state and people, and better fulfil the international commitments.

Contributed by

Phuntsho Namgyel (PhD)

phuntshonamgyel2011@gmail.com