‘Are you ready to die for your country?’ The Bhutanese boy looked at the American man, thought for a moment, and replied, ‘No, that would be crazy. Who would want to die for a country?’ This conversation between a United Nations delegate and a Class X student occurred during the early years of Sherubtse school in Kanglung, Eastern Bhutan.

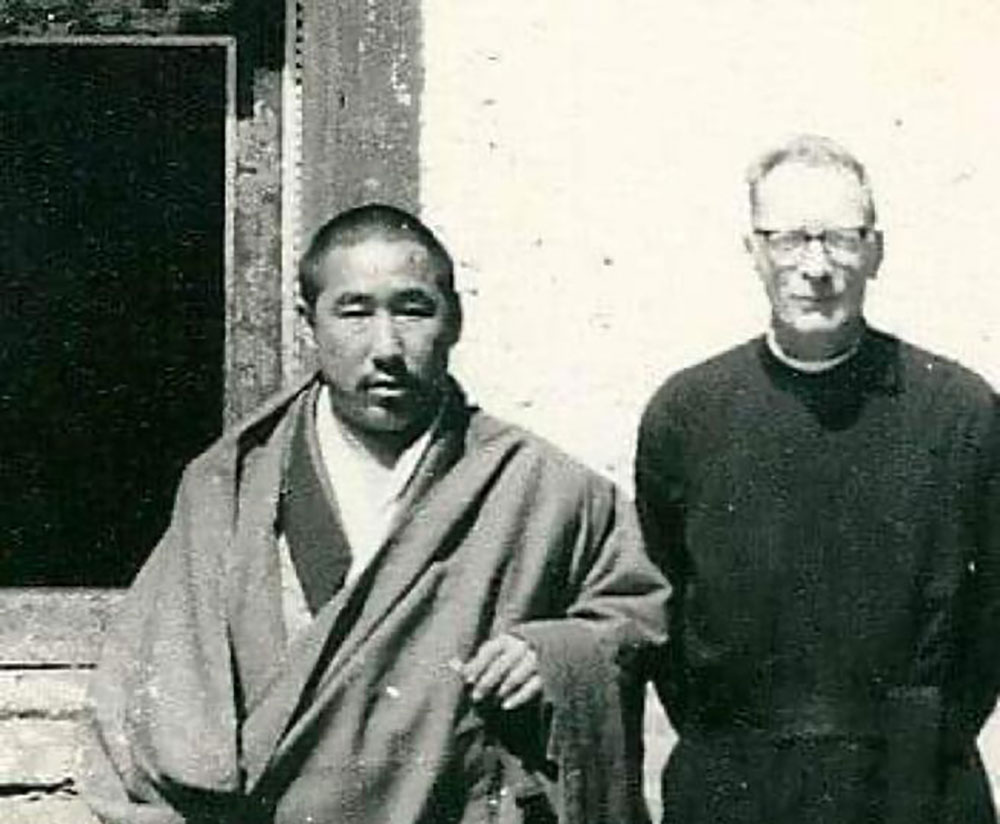

Established in 1968 with 100 students, the Canadian Jesuit, Father William Mackey (1915-1995) was its first principal. He witnessed and recorded the conversation at his school. In his six-page unpublished chapter, “Growth through contact with different Religions and Culture,” the Father said that he had to intervene in the conversation and rephrase the question and asked his student, ‘Are you ready for your king?’ to which the boy promptly replied, ‘All are ready to die for our king.’ Father’s view was that, ‘The concept of country did not exist. Their world was their small village.’

PA: A Member of the Village

In 1963, Father Mackey arrived in Paro after having lived in Darjeeling for 17 years. Unlike the Indian hill station, Father Mackey observed that there was not a town in Bhutan; ‘Thimphu, the present capital was rice fields. Phuntsholing was a small border village, a little bigger than Samdrup Jongkhar in the East. The other District Centers were Dzongs-a good sized monastery with a few political officers. The social units were isolated villages spread over the country. These villages-8 to 15 houses, formed the real Bhutanese social life.’

Father Mackey noticed that most Bhutanese at the time were born in a small village, lived in it and died in it. ‘They would hesitate before moving into the next village-one or two days walk-over difficult mountain passes. These small villages were fantastic social units. Most of the time, there was a Gomchen-defrocked monk-who found married life more interesting than the regular monastic life. They were educated, could read and write Choeki. They were present at birth, marriage, sickness, death. They solved quarrels. They taught the clever children to read and write Choeki. In time of disaster, they guided the village to face any problem that happened to arise.’

Father Mackey said that the center of life was the village. When he first came to Bhutan, when he askd a boy or a girl who they are, the answer will not be a Bhutanese, but a, ‘Mongarpa, a Radhipa, a Bidungpa…PA a member of the village, the social entity for most Bhutanese.’

Roads; the Game Changer

But once the roads started appearing on faces of hills and cut through mountain passes bridging villages and connecting the whole country, the concept of nationhood started to develop. Noticing this change, Father Mackey recorded the impact it made on the same villagers. ‘The first three roads were south to north. Children from villages along the road came to the bigger schools, where they rubbed shoulders, fought, played with boys and girls from other villages. Slowly the concept of a bigger political unit grew-Shashapas, Nalaangpas, Southerner, etc. We do not realize the impact of the lateral road. Slowly the concept of country developed. In our bigger High Schools, children from all over Bhutan formed a social unit, so that the concept of one country came alive. The Southern Bhutanese problem has also strengthened this oneness. Any threat, from outside, unifies the different groups making up a country.’

In page five of the Chapter, Father Mackey writes, ‘one of our major problems is the fact that we have yet to mature into development. Few realise that we have jumped from Middle Ages into modern times in 30 years. All social growth has to be slow. We have not got used to the radical changes in life style. In most families, the grandparents grew up in the middle-aged set up, the parents have one leg in the past and the other in the future. Their children are modern. Is this not the main cause of lack of maturity in our approach and reaction to videos, movies, modern life styles. We are lacking maturity. It will take another one or two generations before Bhutanese, old, middle aged and young, feel at home with modern life. In the last thirty years we have made a cultural leap, which other countries have taken hundreds of years to do.’

Mother Theresa

As Father Mackey lived in a largely Buddhist society he kept an open mind while practicing his own faith. He said that the encouraging feature was Buddhism. Recollecting an anecdote, Father writes, ‘Mother Theresa was invited to Bhutan to set up some of her charitable works. She took one look at the country and refused. Her response was you Bhutanese take care of your sick and needy. There is not an orphan in the country. When the parents die, the village takes care of the children. This attitude may be lost as we become urbanized. So far, the so called, modern Bhutanese city, town dwellers still pray, gather in groups, form burial societies and still help one another. How long will these village ties last? Will the town Bhutanese be able to keep up the social thinking and adapt same to the next century. Modernisation has its pitfalls.’

In a section subtitled, ‘Phase V: Influence of my religious Thinking,’ Father asks, ‘How have I been influenced by Bhutan’s religious thinking and practice? Much of my prayer life, religious reading and other practices, more often than not, stressed an intellectual approach, a fallacy that tries to grasp and understand an infinite reality by a finite mind, word or concept.. Bhutan stresses the fact that an Infinite reality cannot be grasped by a finite intelligence. However, it can be experienced.’

In the last page of the chapter, Father Mackey writes, ‘In our boarding schools, both boys and girls gather for the recitation of Buddhist Prayers. I would often sit down with them and recite my Breviary-psalms and readings from scripture which most religious recite daily. I would recite the same to the Bhutanese prayer, rhythm, trying to have a religious experience. As I wandered through the Dormitories every evening before lights out, I would come across boys squatting on their beds, unconscious of the rumpus around them, experiencing prayer. Slowly, I began to follow their example. I can now squat peacefully for 45 minutes every morning trying to experience the reality of God in my life. Bhutanese guluphulus (rascals) have taught me how to pray.’

Father Mackey goes on to describe his experience. ‘The daily religious practices in an average Bhutanese home goes to show how close they are to reality. The offering of the day with all its troubles, problems good and bad,-one of the children will take the sangphur-little metal cup of vase-in which some leaves or sticks are burning-and waft the smoke in front of their altar, and around the room. It is a daily Bhutanese morning offering of the day, good and bad, difficulties and problems, to Sangye, Lord Buddha, asking for his help and guidance.’

Father Mackey concludes his experience by saying, ‘My approach to prayer in now Bhutanese Trinitarian. I try to experience the reality of being father in being ‘I AM’ an opportunity to be a chance to suffer, work, pray, to make my little world a more loving place. Reality of the son trying to experience Christ’s healing, saving power in my life. Reality of the spirit enkindles in me the fire of divine love, trusting that my little world will be a more loving place. All peacefully, quietly, not through reasoning or intellect, but through an experience of the reality of the trinity in my life.’ Given Father’s attitude to Buddhism, some questioned his Christianity. In his defense, he said that the depth of spirituality he found in Bhutan made him comfortable with proscription against proselytizing.

Small is Capable

Father Mackey lived in Bhutan from 1963 to 1995, a period when modern infrastructure was still developing. While he observed a lack of national character, our written and oral history demonstrates a robust sense of nationhood dating back to the 17th century. Cultural preconceptions may have prevented foreign observers like Father Mackey from recognising the subtle yet deeply ingrained expressions of national character upheld by our forefathers and championed by our successive monarchs.

Despite these limitations in perceiving Bhutan’s national character, Father Mackey’s overall experience in the country was profoundly impactful. Reflecting on his time in Bhutan, Father states, ‘I was able to give a lot, but I received more than I gave.’ He said he was witness to the transformation of a middle-aged village society into a strong, modern democratic Kingdom over three decades, ready to face the challenges of the 21st century. Father Mackey attributed this remarkable progress to the strength and vitality inherited from the last three kings and the wise guidance and foresight of His Majesty the Fourth King, supported by his loyal and democratic government officials. He emphasised that Bhutan’s small size was not only beautiful but also advantageous in facing any challenges that might arise in the first decade of the 21st century. Father Mackey’s student, who once thought dying for one’s country was a crazy idea, went on to become an army officer and served the nation.

Contributed by

Tshering Tashi