Source of Life by Toni Huber

In a breathtakingly wide canvas filled with countless analytical drilling down, eastern Bhutan is lit up in detail for the first time in Huber’s Source of Life.

To be precise his subject is non-Tshangla speaking part of eastern Bhutan consisting of areas where Dzalakha (related to Brag-gsum language spoken by mkhar builders of Tibet), Kurtoedpaikha, Dakpakha, Khengkha, Bumthangkha and Chocha-ngacha (Tsamangkha) are spoken. Sources of old festivals, cultures, languages, folk etymologies, mkhar- architecture, in-migration, and settlements among these East Bodish linguistic speakers of eastern Bhutan have been largely unknown until Huber’s monumental research lasting 15 years.

Title: Source of Life

Author: Toni Huber

Vol I – 640 pages

Vol II – 499 pages

He takes us on an enriching journey of analysis of ancient Tibetan texts as well as of ancient texts in Kurtoepaikha, Dzalakha, Dakpakha, and Bumthangkha. Handwritten folio manuscripts of these Bhutanese dialects provide surprising evidence of our ancestors writing their dialect hundreds of years ago. This direction should be renewed if these languages are to be revitalized and the sensibilities of their cultures maintained.

In the course of his work, Huber translated over 1,000 pages of some 100 manuscripts he came across. Huber’s multi-disciplinary and cross-boundary approach takes us into East Bodish languages through which shared lexicons and concepts have percolated, and over vast geographical expanses from Zhemgang in Bhutan, Subansiri river valleys stretching from Arunachal Pradesh into Tibet, and further east to Yunnan and Sichuan where Naxi and Namuyi people live.

He deepens our understanding in radically new ways about the non-Buddhist cosmology; performances, gesticulations and ritualized bodily movements; verse chants about journey of gods and verse chants accompanying dances; material culture and accessories of rituals; instruments and objects; flora and fauna, including bat, related to the cult; food and vitality substances; and the role of key ritual performers.

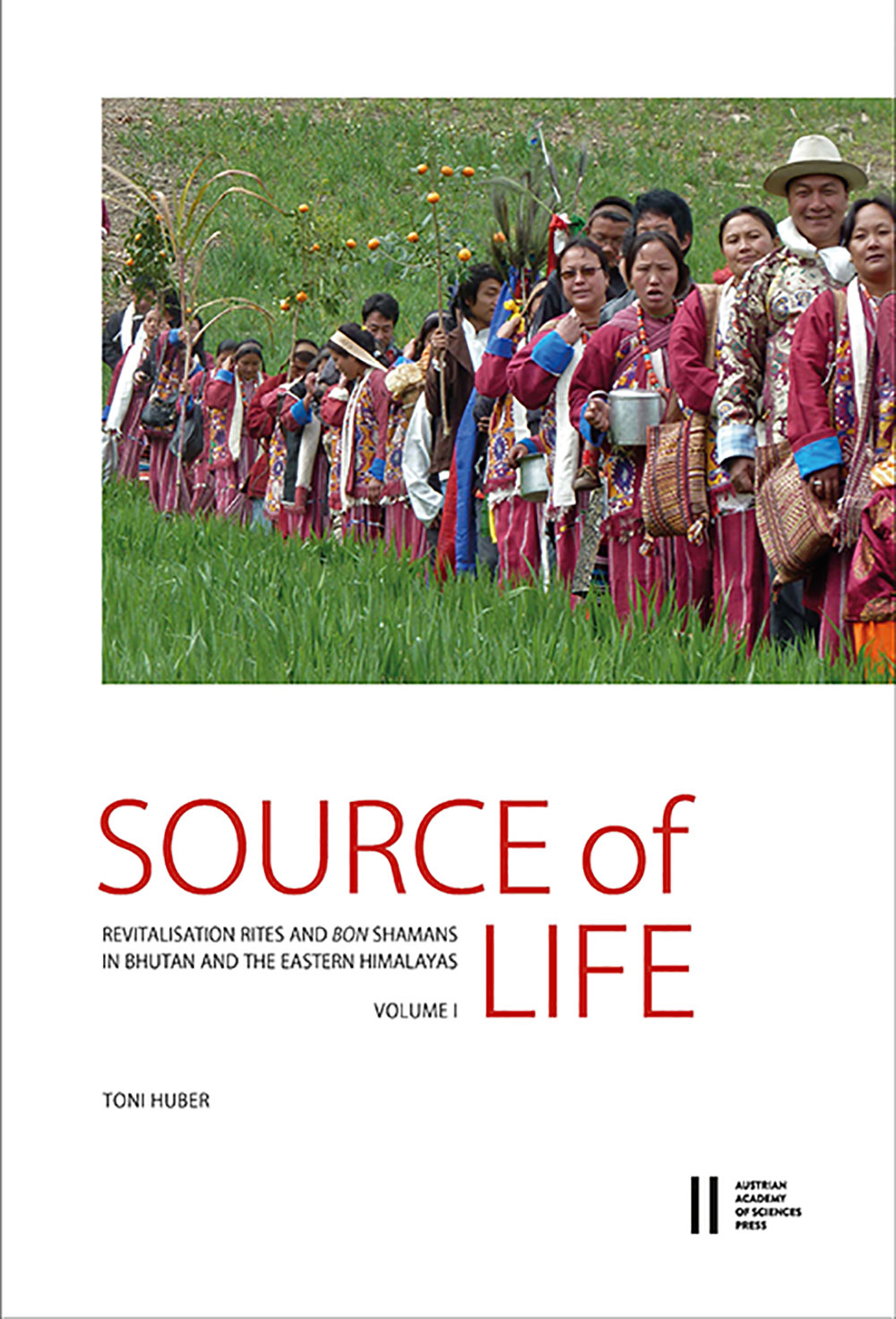

Tsango festival in Khoma

The key ritual specialists are known variously as rup, phajo, kharipa, mi sim, shu’d, gongma, ga-sdang, nami, habon and bonpo depending on location. The techniques of rites include chants, dances, divinations, omens, and prognostications of future; and dreams of the key ritual performer corresponding to dreams of gods since the key ritualists are called lha mi or lha’i mi. His work challenges and shifts our hitherto imprecise and inaccurate perspectives about eastern Bhutan. Huber’s work should not only adorn the shelves of administrators, teachers, and planners, but they should be actively referred to prevent accelerating decline of ancient eastern Bhutanese traditions.

After years of studying Arunachal communities, Huber visited his research area in Bhutan – Tongsa, Bumthang, Zhemgang, Mongar, Kurtoed, Tashi Yangtse and Tashigang – many times between 2009 and 2014 at the invitation of the Centre for Bhutan Studies. The Centre was keen to support such a leading ethnographer also to mark the beginning of the reign of His Revered Majesty who has attached great importance to understanding our nation in all aspects. The result is astonishingly original. The first volume of Source of Life has 640 pages, and the second volume has 499 pages. Its richness and depth have made the book an epic of Himalayan ethnography. Guntram Hazod (2020) acclaimed it in his review as a standard in the field of Tibetan studies and Himalayan ethnography, a class on its own.

Huber’s previous works such as The Cult of Pure Crystal Mountain (1999) about Vajra Varahi’s Tsari Ney and The Holy Land Reborn (2008) demonstrated extraordinary scholarship able to illuminate the often convoluted and complex way in which the pilgrimage hotspots have evolved over millennia and disappeared and got recognized and reappeared elsewhere.

Source of Life maps eastern Bhutan along with contiguous areas of Dirang and West Kameng in Arunachal Pradesh where the worship of Srid-pa’i lha (lha of procreation or the lha of phenonmenal world, as he calls them) has spread, across ethnic and East Bodish linguistic groups. Yet Huber clarifies that it is unique to this area, as at present Srid-pa’i lha worship is confined only to these transborder communities. Though it can be traced back to Lhobrag, none of it exists in Tibet suggesting that it might have been assailed by other religious sects or political forces. Certain aspects of the cult are prevalent among the Naxi of north-west Yunnan and western Sichuan, some 800-1000 km further east along the same geographical stretch. Vol 2 is a rigorous exposition of his new hypothesis that Naxi and Qiang people and the Srid-pa’i lha communities of eastern Bhutan have a shared ancestry, drawing on linguistic cognates and similarities of rites and beliefs.

One of the vital distinctions between Srid-pa’i lha cult on the one hand and Buddhism or Yungdrung Bon on the other is that Srid-pa’i lha cult believes in bla (pla in Dakpakha, pra in Dzalakha, cha in Kurtoedpaikha) as a divisible and multiple vitality principle as opposed to unitary and singular principle in Buddhism. He distinguishes Srid-pa’i lha cult as a social and cultural phenomenon. He considers it not religious, in contrast to Buddhism or Yungdrung Bon. But there is no value judgement intended in distinguishing it as non-religious. Labelling it as non-religious does not mean that it is inferior. Lamas and officials and similarly inclined people are prone to be dismissive about Srid-pa’i lha cult. In fact, this attitude can and has led to discouraging the culture that sustains the communities. A greater and more versatile capacity of the Srid-pa’i lha worshipping communities is that they are multi-polar, being Buddhists as well as honouring Srid-pa’i lha deities and local numina. There is no good reason why they or others cannot have such multiple identities.

In volume 2, Huber disambiguates further the complex and deep cosmology of Srid-pa’i lha cult which differs from Buddhism and Yungdrung Bon. In doing so, three crucial ritual texts for his analysis are the rnel dri ‘dul ba manuscript, and ste’u and sha slungs manuscripts. Huber notes a significant point that word bon does not occur in any of these manuscripts though gshen does a few times. All three of these illustrated texts are dated to the eleventh century and all three originated in Lhobrag in Tibet, quite close to north-eastern Bhutan. These three ancient texts articulated cosmological concepts and mundane rites from an earlier period. Huber characterizes Srid-pa’i lha cult as a continuity and transformation of ideas and rites found in these key manuscripts.

Central to the cosmology of Srid-pa’i lha is the notion of 13 levels of vertical cosmic axis delineated in detail in the three ancient texts. Sky is the highest level in the axis where the lha dwell and terrestrial or earth surface is at the lowest level. Unlike in classical Tibetan or Yungdrung Bon traditions, there is no lower subterranean level beneath terrestrial level. In the cosmology of Srid-pa’i lha, life and vitality flow up and down between the highest lha level and our own world. However, in its cosmology, there are also a range of other negative and positive spirits at various other levels such as sman, mtshun, bdud, gyen, rmu, srin etc. There is also wildlife, especially herbivores on the terrestrial level. Rites maintain the relationship among these multitude of beings. The cult’s rites are directed to keeping the wilderness abundant to support the birth of lha as human beings.

Srid-pa’i lha worship, particularly lha Guse Langling, was first mentioned briefly, in the 1688 book by historian-monk Ngawang of Tashigang in connection with the genealogy of Dung families. Huber asks readers to transcend Ngawang’s Rgyalrigs due to its limitations. Ngawang paid attention to identities of Buddhist clans of Jobo and Zhelngo. However, Ngawang glossed over Srid-pa’i lha communities of Khu, Seru, gNamsa, Mi, Shar, Ba and Na who are still found in the region and who are mentioned in the local manuscript Lha’i gsung rabs he came across in Khoma. Huber charts the distribution and ancient origin of these clans.

Srid-pa’i lha cult reflects pursuit of fertility, reproduction and virility of human beings and their key livestock such as sheep, yaks, and horses. These were popular domestic animals that were dominant in the environment of southern Tibetan Plateau where the cult rose. Thus, a festival or a rite seeks to cultivate tshe (patrilineal fertility), yang (quintessential female reproductive potency) and phya (sky beings) for the worshiping communities, just like tshe-khug yang-khug cha-khug of Vajrayana rites which had perhaps assimilated this ritual technique. Srid-pa’i lha cult is also distinctive from Buddhism and Yungdrung Bon because it claims the existence of various Srid-pa’I lha, the human progenitor, who live in the sky and who is at the centre of its cosmology. Worshipping communities claim common descent from their progenitor-lha, whether they are its chief lha, O-de Gungyal, or his divine son Guruzhe, or other lha. Gurzhe, Guse Langling and many other variations refer to the same lha, Gurzhe, Huber finds. O-de Gungyal and other lha are white, dressed white and ride white horses. They do not bear any arms unlike Vajrayana protector deities. In Kurtoed, an array of siblings (about eight) of Gurzhe such as Namdorzhe, Yang chung and Yum sum is worshipped, and some of them are represented in visual arts photographed by Huber.

Gods of Srid-pa’i lha cult descend from the sky along a magical cord (rmu thag). In rites, they alight on top of tree stands or freshly cut young trees (lha shing) installed on top of houses and return to the sky afterwards, while the ritual specialists chant sonorously the narratives of inbound and out-bound journey of the gods. A cord is attached to a lha shing to conduct revitalizing energies of the gods to the earthly beings. Similarly, vitality and fertility flow down from heaven to the worshippers, indeed into their bodies. The myth of the first King descending from the sky unto Ura village, to govern Monyul, found in the earlier Bhutanese history textbooks, echoes this concept. Readers might recall that in the earlier Bhutanese history texts, the Dung elites rise in Bumthang and diffuse their network of elites across central Bhutan. But the elites’ titles of Dung were muted in eastern Bhutan for reasons yet unclear while later elite titles of khoche, ponche and chosje spread. Modernization has flattened the Dung and other traditional households, along with their social and cultural functions. A less structured society, except for huge inequality of income, is perhaps a loss from a wider point of view.

It is noteworthy that Srid-pa’i lha are vegetarian and their ritual simulacrum and edible offerings are strictly vegetarian. This reality is far from the widespread misconception about its mode of worship and criticisms based on such fundamental misconceptions that exist among many Bhutanese. Meat eaters project their own perception on others.

Srid-pa’i lha tradition was brought along by people known as gDung between 1352-54, the years of conflict between these warrior clans and the emerging centralizing Sakyapa power in Tibet. Reference to gDung in Lhobrag are occur in 7th and 8th century Tibetan documents. gDung has been spelt both with g prefix and without g prefix, as I do here. The first spelling means descendants and the second spelling means primordial. Either way it alludes to original people of a land. gDung were probably, Huber notes, ancient clans in the Tibetan plateau, who stood against pressure of transformation wrought elsewhere by Buddhist post imperial Tibet.

Huber notes that Sakyapa military leaders distinguished gDung people for military campaign convenience into two sub-groups: Lho gDung and Shar gDung. Lho gDung were in southern side of Tibet near Phari while Shar gDung lived in eastern Lho-brag. Shar gDung migrated to Bumthang and eastern Bhutan and other parts of the eastern Himalayas in the middle of 14th century. Huber notes that Lhobrag Sharchu river valley was the main centre for Shar gDung communities until they migrated southwards due to Sakyapa’s military offensive between 1352-54 and destruction of their mkhars. Although historian-monk Ngawang had indicated that Dungs of Bumthang came from south-western Lhobrag, Huber’s reading of Lha’i gsung rabs found in eastern Bhutan confirmed that ancestors of Zhongar gDung migrated from Lhobrag and Gru-shul through another route, i.e., Nyamjang chu valley. Huber characterizes Lha’i gsung rabs as collective memory of migrant clan population. Narrative in Lha’i gsung rabs recalls the backward route to different locations in Lhobrag which the clans left.

However, the in-migration of gDung from adjacent Tibetan highlands does not mean that there were no pre-existing communities in central and eastern Bhutan. Genealogy of Lhase Tsangma’s descendants show that eastern Bhutan was already populated during his arrival centuries earlier. Longchen in his 1355 poem about Bhutan (Ura, 2016) notes that Bumthang and Tongsa were populated, though surprisingly he does not comment on exodus of gDungs. Huber points out that the older communities in eastern Bhutan, whom he calls Mon clans included Na clans (Na mi= Na people), whose worshipped deities known as zhe. For example, Kurtoed Nay/Nas village was most probably settlement of Na people. Autonyms using Na was found also in Tawang where Na clan live today. The meaning of Naxi people living in Yunnan is the same.

Settlements of Shar gDung in eastern Bhutan are associated with their toponyms. Dirang, a Bhutanese territory till 1930s, is a corrupted form of Dung-rang Lungpa that Pema Lingpa visited in late 15th century. gDung dkar is another place names which most likely refers to an important Shar gDung settlement. It is even probable that it was originally known as gDung mkhar and the name became Buddhist over time to hearken to white-conch shaped land.

Mkhar (tall stone towers) was an essential architecture of the gDung. These multi-storied towers are still found in Lhobrag and Sichuan. Readers will remember that mkhars, though shorter and architecturally slightly different from the classical mkhars of the type found in Sichuan, were densely distributed in eastern Bhutan. Carbon dating of timber from the ruins of Tsenkhar la fortress (bTsan-mkar or Mi Zimpa) of Lhase Tsangma traced it back to 1430s. This legendary mkar could have been a consolidation of an earlier structure built by Lhase Tsangma.

The climax of the Srid-pa’i lha worship in any village in eastern Bhutan is calendrical festival. Huber initially found altogether 52 festivals being performed in Bhutan and Arunachal. Huber includes detailed account of such festivals accompanied by instructive high resolution, and aesthetic diagrams and photographs.

In his minuscular study within Bhutan, there is a sharp focus on itineraries, settings and communities surrounding three main festivals. These are the Lhamoche of Tsango in Khomachu valley, the Lawa in Kuri chu valley, and the Aheylha of Changmadung in Kholong chu valley. Documentations of these main rites are informed and supported by data collected from the Kharphu festival in Nyimshong in Chamkhar chu valley, and a series of rites in Tabi, Gangzur, Zhamling, Shawa, Chengling, Ney, Tangmachu, Da, Bumdeling, Khoma, Ura, Tang, Bemji and several other festivals in Arunachal. In general, he finds that festivals occurring west of Nyimshong in Chamkhar chu valley and as far as Mangde valley has become degraded or ceased to be performed. He notes that festivals in eastern Bhutan visibly declined in the span of six years while he was doing field research.

During a festival, the progenitor-lha is invited to descend from the sky into the midst of the associated clans and lineages. In every festival a hereditary ritual expert who can chant rabs, the narrative of the lha’s attributes and journey itinerary, leads the event. Huber notes that there are many versions of rabs, and they are dynamic in that creative ritual experts might spontaneously add to them in the moment of performance. Considering that the practice is dedicated to the fecundity and vitality of men and animal, both domestic and game, representations of human and animal sexuality, full nudity in certain performances, without any unease of the prudish, were the norm in the past.

Jambay Lhakhang drub with its midnight nude-with-mask tercham used to draw throngs of winter tourists briefly flooding the hotels and houses and draining money into the communities of Choskhor. Authentic festivals of eastern Bhutan could sustain both is culture and livelihoods many times more. But nobody will fly thousands of miles just to have a look at beach shorts, or any newly fabricated rite.

Three nights of a festival were demarcated from the normal: people gave permission to themselves to be free to enjoy without any inhibitions and shame. These festival communities maintain that the regime of Zhabdrung was conceded rule over the country, but not over the three days and nights of celebrations. This mutually agreed term must go on, in fact encouraged enthusiastically, if our cultures are not to get impoverished by numbing homogeneity. A general trend in our country has been dissemination and thriving of the same set of dances in different festivals in different places, flattening creativity, depth, and diversity. Huber’s splendid two volumes can be a turning point in the revival of these specific festivals in eastern Bhutan or a documentation of extinct cultures.

Contributed by

Dasho Karma Ura, Ph D