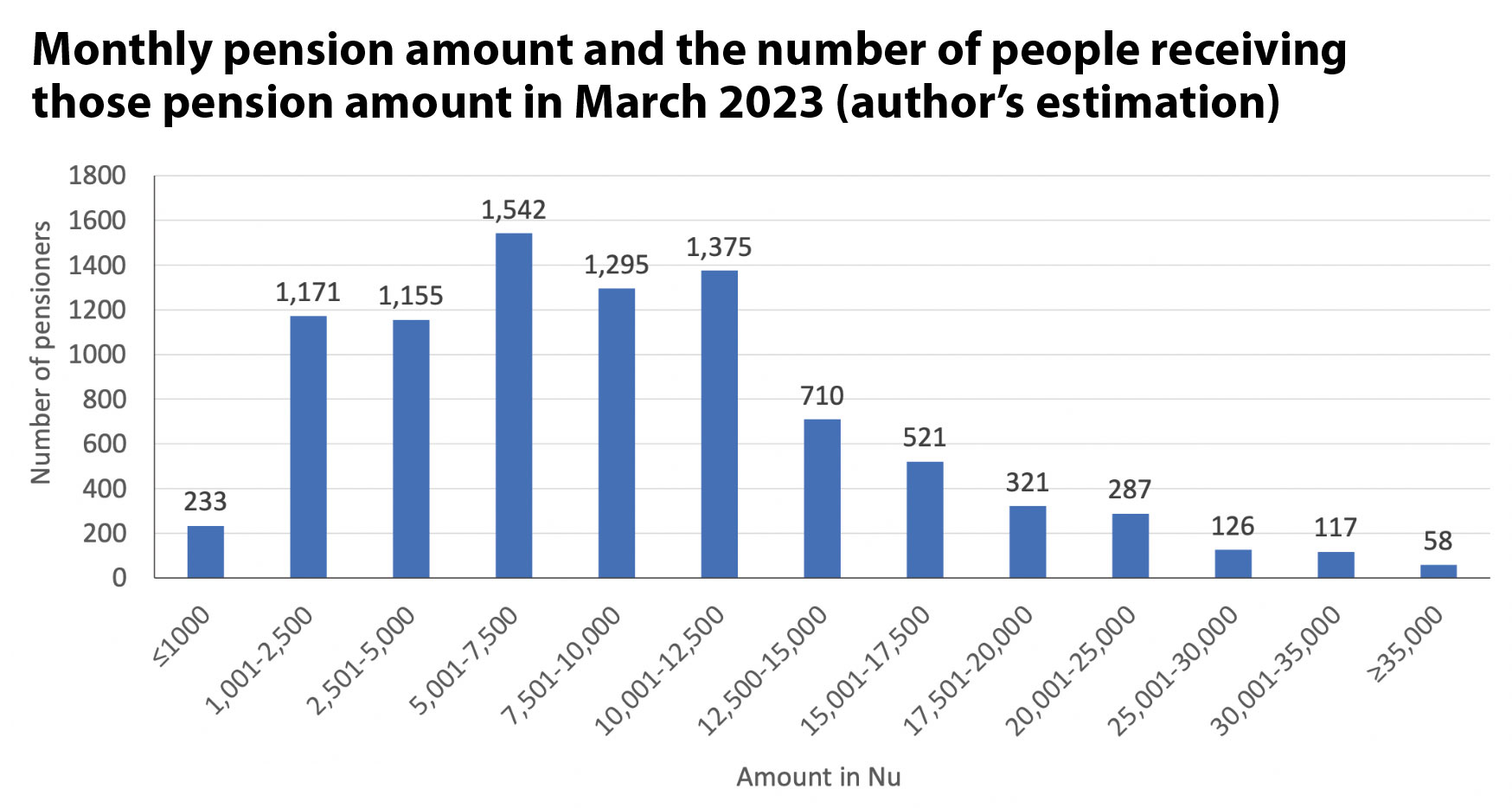

There are currently 9,724 pensioners, and 65,692 contributors in the pension fund. They are naturally sanguine about their retirement, banking partly on fixed amount of pension they will get. The fixed amount of pension is based on formulae. The formula for public servants = (40% * last basic pay * max pensionable service years capped at 30 years) / 30 whereas the formula for armed forces = (45% * average of last 12 months’ salary * pensionable service years) / 27). They might be baffled by the likelihood that pension fund will be exhausted for the military by 2044 and for the public servants by 2064. Goaded by such actuarial estimations about unsustainability of pension, in recent months, external advisors involved in the transformation exercise proposed a shift from defined benefit to defined contribution. The shift from defined benefit to defined contribution will result in less pension by a huge percentage, eroding decent and adequate livelihood for pensioners. At present the median pension per month is Nu 11,236 for a public servant and Nu 7,222 for a soldier. In brief, in defined contribution pension, the amount of monthly payment will be lower and will fluctuate depending on what the National Pension and Provident Fund (NPPF) can earn. There is even no clear rational for pension fund to exist if it is all up to defined contribution. Individuals can invest in instruments and banks where returns can be higher than what NPPF can earn. In defined benefit pension, which is the current system, the monthly amount is fixed and higher, with current contributors largely paying for the retirees. The board of the NPPF does not support this shift to defined contribution. It is unconvinced from the point of view of both social welfare and economic efficiency. It has instead proposed to the government several parametric changes for the time being to improve financial sustainability. A long-term financial sustainability of pension will require a regulatory change in the scope of its lending, like a bank, to improve its rate of return and make it financially sustainable. This long-term measure will be crucial if the present pension system is to become sustainable, to generate enough income to cover deficit over the long term. The earlier this decision is made, faster the future losses will be cut. Pension fund’s board cannot and has not made these desirable changes for so long because pension functions as a state enterprise under Finance Ministry.

Gratuity scheme for soldiers was instituted in 1962. In 1998, HM the 4th King graciously issued a decree to start a pension scheme. It was part of an evolving provision of social security that includes free health and education services, and pension must be viewed within the wider typology of financing social security and services out of the budget. That decree led NPPF to be established vide an executive order in 2000. A pension benefit is a promised monthly amount after retirement for contributions made during employment. Clause 82 of the armed forces rules and regulations says that ‘The RGOB shall guarantee the pension benefits prescribed in the rules and regulations’ just as the clause 113 of the NPPF rules and regulations say, ‘The RGOB shall guarantee the pension benefits prescribed in these rules and regulations.’ Pension benefits is mentioned in the Civil Service Act. The terms ‘pension benefit’ and ‘guarantee’ for the public servants and the military since then have been understood, defined, and practised as defined benefit. Meaning of a terminology is understood and defined in the context of practice. If that were not the case, language as a communication could never succeed. It might be disingenuous for anyone to change the nature of pension from defined benefit to defined contribution without a regulatory change first.

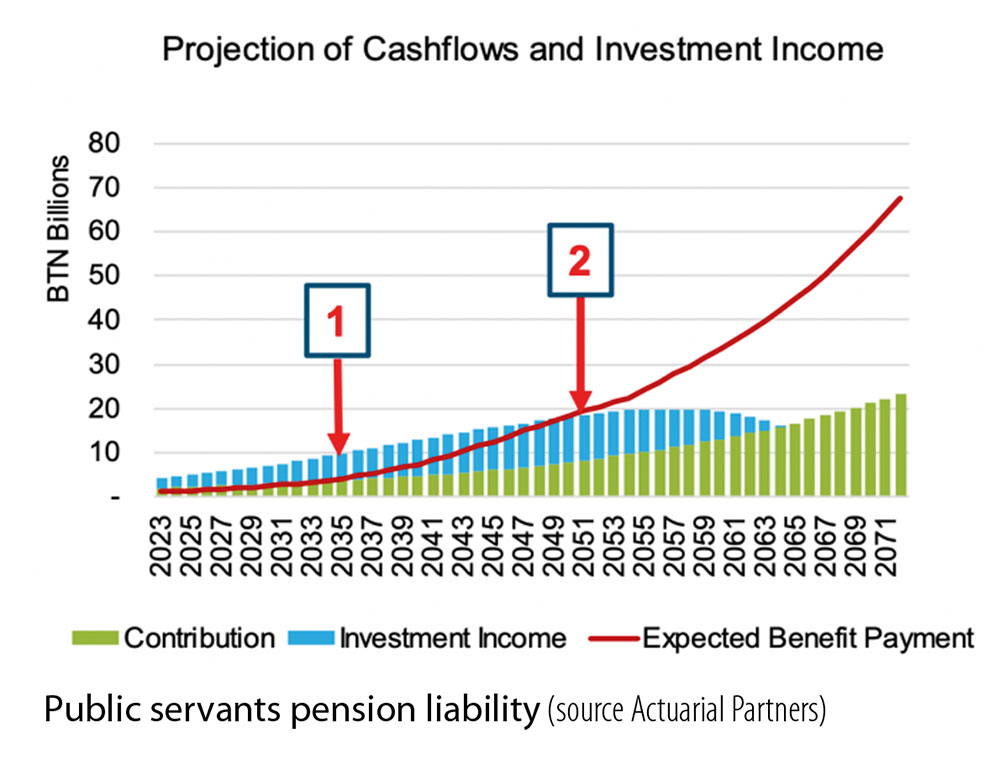

The NPPF has presently an investment fund size of 53 billion (b), which grows every year because the contribution is far greater than pension pay- out at this stage. Currently, 367m is received as pension contribution per month while the pension pay-out is 85m per month. Assuming there are no new contributors joining in the pension, which means that those who leave are replaced by new entrants, and parameters are not changed, this relationship will be flipped sometimes in the early 2030s, and the pay-out will exceed the pension contribution. Further crunch will arise when the pay-out exceeds the pension contribution plus the investment income in 2051 for the public servants and in 2040 for the armed forces.

Most of investment fund – 53b – is held as fixed deposits in the four banks. The amount of fixed deposit is about 22.4b or 40% of the total asset. 6b has been invested in government bonds, of which the interest rate is as low as 5% today. 10.9b are lent to corporations, including DHI companies; and 7.6b are invested as loans to NPPF members. It is important to note that fixed deposits with the banks fetch about 6% interest rate. Largely for these reasons, the current average rate of return on the total invested fund is 6.27%, a sum that does not match even long-term inflation rate and slightly exceeds the pension indexation of 5%. The highest rate of return NPPF had received was 8.5% between 2014 and 2016. If such level of returns can be sustained it will hugely reduce pension deficit. The executive order of 2000 allows NPPF to invest in companies listed on the Royal Securities Exchange of Bhutan and those incorporated under the Companies Act. It is also allowed to invest in real estate development and lend to its members for housing. NPPF is not allowed to invest in non-members for housing, and in trade, commerce, and transport, which can fetch much higher interest rates. In short, it is not allowed to make more money through such lending that generate better returns as evidenced by banks’ performance. Consequently, NPPF must place its money in fixed deposits with banks at relatively lower interest rates even though it has a critical social responsibility.

Restrictions on such kinds of lending were presumably based on the idea that they pose higher risk and NPL to NPPF. Yet this idea proves to not be plausible and cogent. Risks to the banks, which holds NPPF fixed deposits, does not insulate NPPF, because NPPF is so heavily exposed to the few banks in our country unlike other countries where pension fund can be invested in many financial institutions and many types of investment to diversify and reduce risks. Due to the presence of few banks to whom NPPF is heavily exposed, NPPF will decline or sink if they do. NPPF could invest itself instead of depositing in banks who further lend at higher returns for themselves.

Abroad, pension firms have made better returns because they have been allowed to invest in different assets, including hedge funds, private equities, and even crypto currencies.

The overall NPL of all the financial institutions as a percentage of all outstanding loans as of 30.4.2023 stood at 4.3% or 8.47 B (8.4b out of total loan outstanding of 199b). NPPF’s NPL is 1.8% this month, relatively low among the financial institutions.

It was below 1% until the recent economic downturn. Given the economic slowdown caused structurally by the Covid, and further compounded by the tourism policy changes, loan moratorium, and crowding out of private borrowing due to abnormal level of government borrowing from the banks, 4.3% NPL in the economy is not worrisome, in my estimation.

The low returns on NPPF investments – 6.27%, partly due to regulatory restriction, is one of the factors in its unsustainable trajectory. The income forgone for NPPF by such restrictions on lending directly to housing, trade, commerce, and transport areas is costly contributing to financial unsustainability. Diversification and deconcentrating of investment will reduce risk for NPPF while vastly improving returns and sustainability. Sensitive risk handling should go hand in hand higher returns.

An overwhelming number are contributors (65,692) are yet to retire and receive their pension, compared to 9724 pensioners. Estimation of the amount needed to pay for the current and future pensioners, until the end of their survival which is assumed to be at 72 shows that 33b extra must be earned to cover that deficit over the next 33 years. If we break up this deficit, about 22b is for the public service pension and 11b is for the armed forces pension.

The main question is how to earn enough income to cover deficit of 33b that will emerge over the next 33 years or so, if the number of members in pension scheme remains constant. NPPF can work out a new investment strategy leading towards sustainability as outlined briefly here, or the government can subsidize it over time. The RGOB presently has an external debt of 241b owed to foreign institutions and governments and an internal debt of 27b borrowed from the handful of Bhutanese banks. The total debt stock of 267b does not include the interest rate component; debt stock is a measure only of principle component. RGOB’s debt service levels might not allow for subsidy injection of such magnitude into the pension fund.

Switching to defined contribution for all future members of pension from the day of any new decision will result in a huge payment of 33b adding to government’s abnormal deficit, and a lower pension to all future members of pension. As the amount drawn under defined contribution will be significantly lower, pension for future members under defined contribution will lead to inadequate living condition for most of the armed force personnel and public servants, undermining security in retirement period. Defined contribution is thus a lose-lose option because the RGOB must plug the foreseen deficit and the future pensioners must accept a significantly lower pension amount.

The option that is most viable addressing coverage and adequacy is in fact to continue the present defined benefit with changes in several parameters, each of which will contribute partly to the reduction of deficit across the future. Factors to be changed should include: (a) Raising the pension commencement age (this has happened already to some extent). (b) Rejigging the formula so that last basic pay is not the overwhelming determinant of monthly pension. Frequent salary rise along with linking pension to last drawn salary makes the defined benefit scheme unsustainable and is currently the greatest risk factor for unsustainability and unfairness. The degree of correlation between contribution and the pension amount is so weak because the last drawn salary entitles pensioners to get a high amount throughout the retirement period for which he has not contributed sufficiently throughout the employment period. In addition, linking it to the last salary introduces an element of unfairness of two kinds. First kind is the unfairness of pension between early and recent pensioners. Those who retired just before salary rise and after the salary rise get different pension levels though their contributions are almost same. Second kind of unfairness or disparity relates to those between upper and lower positions. Since salary increases in absolute terms have always been greater for higher positions compared to the rest, the current formula rewards the upper positions disproportionately. Thus, a geometric mean of the last 10 years salaries will be fairer. Average of five years’ salary will not make significant difference because the tenure of most high positions with the same level of basic salary is for five years. (c) Increasing the contribution on the part of the employees. Employee contribution rates must be increased by at least 6%. These three changes will plug the deficit to some extent and bring down the deficit from 33b to 21b.

The biggest factor that will reduce the remaining deficit is to increase the rate of return by allowing NPPF to invest in transport, commerce, housing and unincorporated companies or business, just like the banks do, but which are off limit for NPPF due to current restrictions. Allocating the largest chunk of fund – 22b – as fixed deposit in banks is both risky and poor business. Moreover, the interest is on government bonds is now so low – 5%. Investing in them are the laziest option that will cause revenue loss when inflation is considered. Tinkering the executive order is required to broaden the scope of NPPF lending by lifting the current restrictions, which serve no prudential purpose. In fact, they hamper NPPF from investing in higher yielding sectors and create widening deficits that the government will be compelled to take on later.

A scenario building confirms that if the rate of return on investments of NPPF can be increased to 8.75%, the deficit can be reduced from 33b to 19b. Any rate of return is also the rate that can be used to discount the future cash flow. Furthermore, if the rate of return can be increased to 9.75% the deficit can be reduced to 8b. If the rate of return can be pushed to 11%, the deficit will be plugged as earning such high rate of return can cover the deficit over the next 33 years. But such a high rate might be overly ambitious, and considering volatility, a strategy to push it up to 8.75% is realistic. In combination with other parametric changes, income generated can cover the deficit over the next three decades. This solution has triple benefits. Firstly, the government can save money because it does not have to plug the deficit. Secondly, pensioners will continue to get a more decent amount compared to what they will under defined contribution. Thirdly, the economy stands to benefit more because the loanable amount to the public will increase in the sectors that are currently restricted for no good reason. If a timely decision is not made by all parties concerned, the pension fund will be empty, for the military by 2044 and for the public servants by 2064, assuming the size of the members is constant. As more people join the pension scheme and increase contributions, these deadlines of insolvency will be pushed further away but the deficit will grow over time without incorporating the change proposed.

Contributed by

Karma Ura